MADAME AND TWO GENERALS

John Ralston Saul on

Thailand's determination to resist invasion

SITTING weekend after weekend in Thai- land on the east shore of the Gulf of Siam far from the noise of Bangkok, waiting for the next drink to arrive while watching the sun set over the water, it is difficult not to mistake the thunder of the afternoon rain for a bomb exploding on the Cambodian border. Two hundred miles behind, across a few hills, the fighting continues. In a novel, the thunder would indeed be a bomb and the dancing would go on. In this case, reality creeps very close to fiction. For example, if the Vietnamese decided to come for a swim, wiping out the Khmer rebels and the Thai army on their way, they could leave their camps before tea and be with us in time for drinks and a moonlight dip.

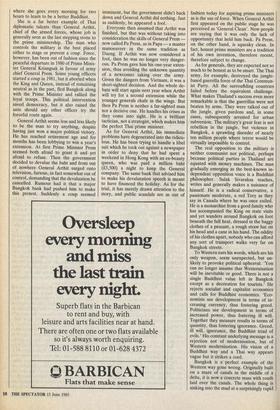

'They won't come,' is on the lips of every Thai and every resident foreigner. Not, They can't come,' but they won't. The only person I know who openly thinks they might come is a very rich woman. Daeng is Perhaps the most successful 'madame' in the world, with 500 girls under her wing. At the age of 40 she has withdrawn into respectable semi-retirement. Her bars and massage parlours are all farmed out to relatives in return for a percentage of the take, delivered weekly in cash to her in the country. Three and a half million dollars out of her capital have been sunk into building an 18-hole golf course 30 miles outside Bangkok. She has abandoned the 9-strings of Patpong to live in what for her Is a new sort of club house. The very existence of her 'country club' borders on the miraculous as it lies below sea level in permanently flooded rice paddy country. Its survival depends upon a maze of dikes and a battery of constantly pumping pumps.

Daeng arrived in Bangkok from the north 20 years ago, aged 20, with two children and no money. She had been married at 13 in her village, where she began family life immersed up to her haunches planting rice in just the sort of paddies she has recently been converting into fairways. Seven years later, she left her husband in the mud and came to Bangkok, where she became a pound a night hostess at the old Café de Paris. Her intelligence, however, outweighed her per- sonal entertainment skills and with a bit of help she began building an empire of bodies.

The other day in her club house, I asked Daeng about the Vietnamese. She admit- ted: 'Thai people, they don't like to fight. Vietnamese different. They fight all the time. Thai army no good. But if Viet- namese come, they cannot beat Thai people.'

The Vietnamese, I pointed out, Com- munists that they are, would close her golf course.

'I don't care. Maybe I lose this place. So what? Vietnamese men fight like lions. So they need Thai girl.'

The theory that the Thai army will lose the battle while the Thai people will win some sort of protracted guerrilla war is a private view which often comes out in prolonged private conversations. What it shows, along with the fighting on the Cambodian border and the continuing flow of refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia and increasingly Laos, is that the Vietnam war is not over. America's recent celebrations of its own defeat were not only in dubious taste. They were historically inaccurate, because not even for the United States is the war over.

After all, if it were over, why would Washington be selling the F16, its most sophisticated fighter, to the Thai air force? And why would America be supporting the legal rights of the Khmer Rouge, the bloodiest Communist regime in recent history? No, the war is still raging. Men are still dying. Not Americans for the moment, but the Nato countries and all of our Far Eastern allies are directly involved through investment, military hardware and political commitments.

As the Vietnamese huddle on the Thai border, charging over from time to time to attack specific targets, an unexpected phrase echoes through the air — the domino theory. Child of the 1960s, discre- dited and forgotten, suddenly here it is, alive and well and at the heart of the foreign policies of Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and even, after a remarkable evolution, of Burma.

The Vietnamese won't come, people say, because Hanoi is so poor and so bogged down fighting in Cambodia that it has neither the money nor the troops for another adventure. Unfortunately, when warring nations are in trouble, they often do something irrational. The United States, for example, intervened in Cambo- dia because they couldn't handle the Viet Cong who were hiding behind Sihanouk's border. The Vietnamese problem today is identical, with the Khmers hiding behind the Thai border.

Believing that nothing will happen is not unlike Daeng's conviction that even if it does, everything will work out. Thailand, after all, has kept its independence over the centuries not by defeating neighbours, colonial powers and communists, but by outmanoeuvring them. Talleyrand in Thai- land would have been an amateur. They somehow make even the worst situations work in their favour.

Daeng's 500 girls, for example, are but one per cent of the half a million prosti- tutes in Bangkok. This terrible figure ought to invoke horror, and of course there are terrible stories — the girls burnt to death last year in a Phuket fire spring to mind. They were chained to their beds. And yet one is forced to admit that an average girl can make two or three times with her body what she can make in a factory or as a secretary. Her profession carries no terrible social stigma. She quite probably sends money home regularly to her village and may even retire there one day to settle down, respected and richer than her neighbours. Daeng herself is not going back to any village, but she has donated a large slice of land on the edge of her golf course to some Buddhist monks and has built them a contemplation centre where she goes every morning for two hours to learn to be a better Buddhist.

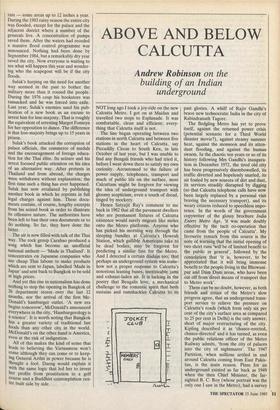

She is a far better example of Thai diplomatic talents than General Arthit, chief of the armed forces, whose job is generally seen as the last stepping stone to the prime ministership. The man who controls the military is the best placed either to stage or prevent a coup. Force, however, has been out of fashion since the peaceful departure in 1980 of Prime Minis- ter General Kriangsak in favour of army chief General Prem. Some young officers started a coup in 1981, but it aborted when the King and Queen, instead of remaining neutral as in the past, fled Bangkok along with the Prime Minister and rallied the loyal troops. This political intervention saved democracy, but it also raised the ante should any other officer try the forceful route again.

General Arthit seems less and less likely to be the man to try anything, despite having just won a major political victory. He has reached retirement age and for months has been lobbying to win a year's extension. At first Prime Minister Prem seemed both afraid to grant it and yet afraid to refuse. Then the government decided to devalue the baht and from out of nowhere General Arthit surged onto television, furious, in fact somewhat out of control, demanding that the devaluation be cancelled. Rumour had it that a major Bangkok bank had pushed him to make this protest. Suddenly a coup seemed imminent, but the government didn't back down and General Arthit did nothing. Just as suddenly, he appeared a fool.

Everyone then assumed that Arthit was finished, but that was without taking into consideration the skills of General Prem — now called Pa Prem, as in Papa — a master manoeuvrer in the same tradition as Daeng. If Arthit was now considered a fool, then he was no longer very danger- ous. Pa Prem gave him his one-year exten- sion, thus avoiding the unknown quantity of a newcomer taking over the army. Given the dangers from Vietnam, it was a short-sighted decision. And the whole de- bate will start again next year when Arthit will try for a second extension while the younger generals chafe in the wings. But then Pa Prem is neither a far-sighted man nor a decisive one. He handles his crises as they come into sight. He is a brilliant tactician, not a strategist, which makes him the perfect Thai prime minister.

As for General Arthit, his immediate problems have degenerated into the ridicu- lous. He has been trying to handle a libel suit which he took out against a newspaper in order to deny that he had spent a weekend in Hong Kong with an ex-beauty queen, who was paid a million baht (£3,500) a night to keep the General company. The same bank that advised him to make his devalutation speech is meant to have financed the holiday. As for the trial, it has merely drawn attention to the story, and public scandals are as out of fashion today for aspiring prime ministers as is the use of force. When General Arthit first appeared on the public stage he was perceived as 'General Clean'. Now people are saying that it was only the lack of opportunity that held him back. Pa Prem, on the other hand, is squeaky clean. In fact, honest prime ministers are a tradition of his own invention, therefore recent, therefore subject to change.

As for generals, they are expected not so much to be honest as to be smart. The Thai army, for example, destroyed the jungle- based guerrilla force of the Thai Commun- ist Party. All the surroudding countries failed before the equivalent challenge. What makes Thailand's success even more remarkable is that the guerrillas were not beaten by arms. They were talked out of the jungle, given pardons and„ in some cases, subsequently arrested for urban subversion. The military's great fear is not rebellion in the jungle, but violence in Bangkok, a sprawling disorder of nearly ten million people where terror would be virtually impossible to control.

The real opposition to the military is neither communist nor political, perhaps because political parties in Thailand are equated with money machines. The man gradually emerging as the best-known in- dependent opposition voice is a Buddhist philosopher. Sulak Sivaraksa teaches, writes and generally makes a nuisance of himself. He is a radical conservative, a passicinate moderate, a red Tory as they say in Canada where he was once exiled. He is a monarchist from a good family who has accompanied the King on state visits and yet wanders around Bangkok on foot beneath the full heat, dressed in the baggy clothes of a peasant, a rough straw hat on his head and a cane in his hand. The oddity of his clothes apart, nobody who can afford any sort of transport walks very far on Bangkok streets.

To Western ears his words, which are his only weapon, seem unexpected, but un- likely to provoke political upheaval. 'You can no longer assume that Westernisation will be inevitable or good. There is not a single Buddhist value left in Bangkok except as a decoration for tourists.' He rejects socialist and capitalist economics and calls for Buddhist economics. 'Eco- nomists see development in terms of in- creasing currency, thus fostering greed. Politicians see development in terms of increased power, thus fostering ill will.

Together they measure results in terms of quantity, thus fostering ignorance. Greed, ill will, ignorance, the Buddhist triad of evils.' His constant underlying message is a rejection not of modernisation, but of Western modernisation. His vision of a Buddhist way and a Thai way appears vague but it strikes a cord.

Bangkok is a perfect example of the Western way gone wrong. Originally built on a maze of canals in the middle of a delta, it is now a concrete mass with roads laid over the canals. The whole thing is sinking into the mud at a surprisingly rapid rate — some areas up to 12 inches a year. During the 1983 rainy season the entire city was flooded, except for the palace and the adjacent district where a number of the generals live. A concentration of pumps saved them. After the waters had receded a massive flood control programme was announced. Nothing had been done by September 1984, but a remarkably dry year saved the city. Now everyone is waiting to see what will happen this year and wonder- ing who the scapegoat will be if the city floods.

Sulak's harping on the need for another way seemed in the past to bother the military more than it roused the people. During the 1976 coup his bookstore was ransacked and he was forced into exile. Last year, Sulak's enemies used his pub- lication of a new book as an excuse to arrest him for lese-majesty. That is roughly the equivalent of arresting Margot Fonteyn for her opposition to dance. The difference is that lese-majesty brings up to 15 years in prison.

Sulak's book attacked the corruption of palace officials, the commerce of medals and the encouragement of foreign educa- tion for the Thai elite. Its seizure and his arrest focused public attention on his idea of an alternative way. After protests in Thailand and from abroad, the charges were withdrawn without explanation; the first time such a thing has ever happened. Sulak has now retaliated by publishing another book in which he reprints in full legal charges against him. These docu- ments contain, of course, lengthy excerpts from his seized book in order to illustrate its offensive nature. The authorities have been left to ban their own documents or to do nothing. So far, they have done the latter.

The air is now filled with talk of the Thai way. The rock group Carabao produced a song which has become an unofficial national anthem — 'Made in Thailand'. It concentrates on Japanese companies who use cheap Thai labour to make products Which are sent to Japan, labelled 'Made in Japan' and sent back to Bangkok to be sold at high prices.

And yet this rise in nationalism has done nothing to stop the opening in Bangkok of 26 department stores over the last 12 months, nor the arrival of the first Mc- Donald's hamburger outlet. 'A new era begins tomorrow', McDonald's announced everywhere in the city, 'Hamburger°logy is a science'. It is worth noting that Bangkok has a greater variety of traditional fast foods than any other city in the world. McDonald's on the other hand is America, even at the risk of indigestion.

All of this makes the kind of sense that leads to believing the Vietnamese won't come although they can come or to keep- ing General Arthit in power because he is thought a fool. Daeng would explain it With the same logic that led her to invest her profits from prostitution in a golf course and a Buddhist contemplation cen- tre built side by side.

Previous page

Previous page