Photography

Like a One-eyed Cat: Photographs by Lee Friedlander 1956-1987 (V & A, till 25 August)

Collected on camera

Ruth Guilchng

The Americans have the strongest tradi- tion of self-documentary photography in the world, a phenomenon which seems wholly appropriate , for a national con- sciousness obsessively concerned with anal- ysis, its own historical inheritance and the metamorphosis of its society. It is possible to trace a direct line of inheritance through the masters of modern American docu- mentary photography — each passing on the torch to the next, each generation growing predictably more disaffected — from the convinced, socialist-realist por- traits of Walker Evans to the more dispas- sionate Robert Frank, the maverick desperado Diane Arbus and now the heir to all this and more, Lee Friedlander, described by the curator of this exhibition as photography's greatest craftsman today.

Herein lies one of the oldest dilemmas in the history of photography: its status as an art form, and the justification for its claims of wider relevance. If Friedlander is really no more than an outstanding photographic craftsman — as is a whole modern genera- tion of Japanese tourists — then why the long-winded essay in the exhibition's accompanying catalogue, with its grandiose claims? 'He provides us with a new visual world . . . like the Dadaists, he is breaking some of the rules of art and reforming oth- ers to suit his wit and intuition.' The com- positions which he has contrived are praised for their density and the layers of

meaning which they yield up, which 'serve metaphorically to address complex issues in the culture at large, beyond the meaning of what was in front of the camera'. It is claimed that Friedlander's images have actually replaced and transcended the writ- ten word, but conversely these same images have spawned a mass of commentary and critical interpretation, much of which is both pompous and cliched.

But whether one views him as a master of reportage or as yet another cultural guru, Friedlander's work is both visually and intellectually interesting. As a young man, he began his career by taking pho- tographs on the street, juggling the intru- sive and the detached persona. One of the earlier series in this exhibition, from the 1960s, makes a play of the merged images of reflection and transparency through the windows of diners and launderettes, but a closer perusal reveals the omnipresence of the photographer, whose shadow image is always superimposed on and mingling with his subject. References to the work of other photographers — Weegee, Walker Evans and Robert Frank — abound, but perhaps some of these recognised similari- ties proceed more from a shared subject matter, the American Dream gone sour, than from a common viewpoint.

A series of self-portraits taken over five consecutive years in the 1960s draws heavi- ly on the argot of the 'Beat' generation. Under a raking light, or leaning against a booth vending soft porn snapshots, Fried- lander is the disaffected 'white Negro' of Norman Mailer's invention. 'Self-portrait, Haverstraw, New York, 1966' might well serve as the cover illustration for Jack Ker- ouac's seminal text, On the Road. This close-up shot shows the photographer at the wheel of his Cadillac, hands gripping the wheel, fixing the open road with an intense stare, but the static quality of little white chalets glimpsed through the rear

window and an obtrusive black shadow on the bonnet reveal the site of the camera and shatter all illusions of speed at a blow.

Every conceivable subject has been col- lected and collated by Friedlander's cam- era — landscapes, urban and pastoral, nudes, still-lifes, animals, even his own family, whose ambivalence on facing the camera lens seems as strong as that on the part of the photographer. Thus, in the most arresting picture of the series, the expres- sion of resigned dismay on the face of his wife, who, 'captured' rather than posed in a state of deshabille, clutches a towel to her chest in an instinctive gesture of modesty and self-protection.

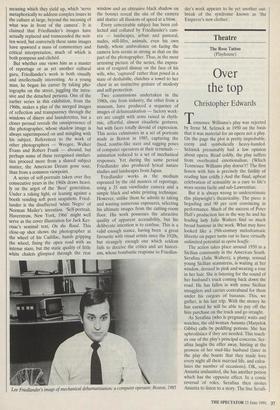

Two commissions undertaken in the 1980s, one from industry, the other from a museum, have produced a sequence of images of dehumanisation — factory work- ers are caught with arms raised in rhyth- mic, effortful, almost ritualistic gestures, but with faces totally devoid of expression. This series culminates in a set of portraits made in Boston in 1985, capturing the fixed, zombie-like stare and sagging poses of computer operators at their terminals — animation reduced to a set of mechanical responses. Yet during the same period Friedlander also produced lyrical nature studies and landscapes from Japan.

Friedlander works in the medium espoused by the old masters of reportage, using a 35 mm viewfinder camera and a simple black and white printing technique. However, unlike them he admits to taking and wasting numerous exposures, selecting his ultimate images from the cutting-room floor. His work possesses the attractive quality of apparent accessibility, but his deliberate intention is to confuse. This is a valid enough stance, having been a great favourite with visual artists since the 1920s, but strangely enough one which seldom fails to deceive the critics and art histori- ans, whose bombastic response to Friedlan- Lee Friedlander's image of mechanical dehunzanisation: a computer operator, Boston, 1985 der's work appears to be yet another out- break of the syndrome known as 'the Emperor's new clothes'.

Previous page

Previous page