Late call to Penguin Man

Gavin Stamp

These days it is not the traditionalists in architecture who are backward- looking; it is the modernists. First we have Mr Peter Palumbo preparing to sweep away a sizeable chunk of the City of London to erect a skyscraper designed in the Sixties by Mies van der Rohe, who died in 1969. Now the RIBA has decided to award its Gold Medal to Berthold Lubetkin. Not that Mr Lubetkin is dead ŌĆö happily he is still very much with us ŌĆö it is just that he retired in 1951 and that the buildings which have won him this honour were designed almost half a century ago. These include the celebrated Penguin Pool in London Zoo: almost an ikon in Modern Movement hagiography and countlessly illustrated in architectural books of the Thirties and Forties. To read the RIBA's Gold Medal citation one might think that nothing has happened since. Berthold Lubetkin is an enigmatic and deliberately mysterious figure in British ar- chitecture. He was born in Tiflis, Georgia, in 1901, the son of an admiral, and educated in St Petersburg and Moscow- 111 1922 he left Soviet Russia for Berlin where he helped arrange an exhibition of pro- gressive Soviet art. He then moved to War- saw and in 1925 to Paris, never, apparently, returning to Russia although he remained In contact with Soviet architects and was Marxist in outlook. Having practised at' chitecture in Paris with Jean Ginsberg, Lubetkin moved to London in 1931, when conservative, provincial England seemed ripe for the introduction of the New Ar- chitecture of the Continent. In 1932 readers of the Architectural Review were treated to a special number on architecture and politics in Soviet Russia. While Robert Byron reported that 'I found it difficult to concentrate my attention on buildings that might cause an ephemeral surprise in the suburbs of Wolverhampton, Lubetkin ŌĆö preposterously described as 'one of the famous proletarian architects (although he had come second in the Palace of the Soviets competition) ŌĆö reassure(' English readers that 'Soviet architects feel no animosity towards theories (as do their colleagues in capitalistic countries) because their ambition is not simply to build ar- chitecturally, but to build socialisticallY as well'. ErnO Goldfinger, who knew Lubetkin in Paris before both architects came to London, recalls how 'he had some mythology of social architecture' something which, in lesser hands in the Fn: ties and Sixties, would cause so much mischief and unhappiness.

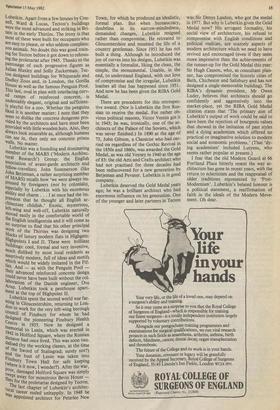

The modern architectural partnership called Tecton was formed in 1932: osten- sibly anonymous but, in fact, dominated by Lubetkin. Apart from a few houses by Con- nell, Ward & Lucas, Tecton's buildings were the most advanced and striking in Bri- tain in the early Thirties. The irony is that most of these were built for occupants who are easy to please, or who seldom complain: zoo animals. No doubt this was good train- Mg for Tecton before it got down to rehous- ing the proletariat after 1945. Thanks to the Patronage of such progressive figures as Julian Huxley and Solly Zuckerman, Tec- ton designed buildings for Whipsnade and Dudley Zoos and, in London, the Gorilla House as well as the famous Penguin Pool. This last, oval in plan with interlacing curv- ed ramps of reinforced concrete, is undeniably elegant, original and sufficient- ly playful for a zoo. Whether the penguins liked it is another matter: I note that they seem to dislike the concrete dungeons pro- vided by the architects and have since been provided with little wooden huts. Also, they always look miserable as, although humans can see in, they only see concrete prison walls. No matter.

Lubetkin was a founding and dominating member of the MARS ('Modern Architec- tural Research') Group: the English association of avant-garde architects and fellow-travellers; John Summerson (like John Betjeman, a rather surprising member of MARS) recalls how 'we were always im- pressed by foreigners (not by colonials), especially by Lubetkin with his enormous ability and charm . I at once had the im- pression that he thought all English ar- chitecture childish.' Exotic, mysterious, left-wing and well-off, Lubetkin naturally Moved easily in the comfortable world of the English intelligentsia and it will come as no Surprise to find that his other principal Work of the Thirties was designing two blocks of luxury modern flats in Highgate: Highpoints I and II. These were brilliant buildings: cool, formal and very inventive, Touch disliked by most local residents as assertively modern, full of ideas and motifs Which would be widely imitated in the Fif- ties. And ŌĆö as with the Penguin PoolŌĆö their advanced reinforced concrete design could never have been built without the col- laboration of the Danish engineer, Ove AruP. Lubetkin took a penthouse apart- ment at the top of Highpoint II. Lubetkin spent the second world war far- ri,ung in Gloucestershire, returning to Lon- don to work for the very left-wing borough council of Finsbury for whom he had designed the pioneering Finsbury Health Centre in 1935. Now he designeda Memorial to Lenin, which was erected in 1942 in Holford Square, where the Russian dictator had once lived. This was soon van- dalised (by the working classes, at the time Of the Sword of Stalingrad; surely not?) and the bust of Lenin was taken into t'insh

-urY Town Hall for safe keeping

ŌĆśWhere is it now, I wonder?). After the war, ...P┬░0r, damaged Holford Square was simply ,.,wept away for monstrous Bevin House ŌĆö nats for the proletariat designed by Tecton. The last chapter of Lubetkin's architec- Tral career ended unhappily. In 1948 he as appointed architect for Peterlee New

Town, for which he produced an idealistic, formal plan. But when bureaucracy, doubtless in its narrow-mindedness, demanded changes, Lubetkin resigned rather than compromise. He retreated to Gloucestershire and resumed the life of a country gentleman. Since 1951 he has not built a thing. Although he introduced the joy of curves into his designs, Lubetkin was essentially a formalist, liking the clean, the simple, the monumental. Unable, in the end, to understand England, with our love of compromise and the irregular, Lubetkin loathes all that has happened since 1951. And now he has been given the RIBA Gold Medal.

There are precedents for this retrospec- tive award. (Nor is Lubetkin the first Rus- sian to receive the medal. For rather ob- vious political reasons, Victor Vesnin got it in 1945; he was, ironically, one of the ar- chitects of the Palace of the Soviets, which was never finished.) In 1890 at the age of 73, John Gibson, a Classicist who had car- ried on regardless of the Gothic Revival in the 1850s and 1860s, was awarded the Gold Medal, as was old Voysey in 1940 at the age of 83: the old Arts and Crafts architect who had not practised for three decades had been rediscovered for a new generation by Betjeman and Pevsner. Lubetkin is in good company. Lubetkin deserved the Gold Medal years ago; he was a brilliant architect who had enormous influence on his generation. One of the younger and later partners in Tecton was Sir Denys Lasdun, who got the medal in 1977. But why is Lubetkin given the Gold Medal now? His arrogant formality, his social view of architecture, his refusal to compromise with English conditions and political realities, are scarcely aspects of modem architecture which we need to have revived and encouraged (even if they seem more impressive than the achievements of the runner-up for the Gold Medal this year: Sir Hugh Casson, who, as consultant plan- ner, has compromised the historic cities of Bath, Chichester and Salisbury and has not designed a single memorable building). The RIBA's dynamic president, Mr Owen Luder, believes that architects should go confidently and aggressively into the market-place, yet the RIBA Gold Medal citation states that 'The primary aim of Lubetkin's output of work could be said to have been the rejection of bourgeois values that showed in the imitation of past styles and a dying academism which offered no practical or imaginative solution to modern social and economic problems.' (That 'dy- ing academism' included Lutyens, who seems rather popular at present.) I fear that the old Modern Guard at 66 Portland Place bitterly resent the way ar- chitecture has gone in recent years, with the return to eclecticism and the reappraisal of older traditions represented by 'Post- Modernism'. Lubetkin's belated honour is a political statement, a reaffirmation of faith in the ideals of the Modern Move- ment. Oh dear.

Previous page

Previous page