It takes guts

Jonathan Ray

or some reason — such as sheer bloody-mindedness — a few days after his 75th birthday my father announced that he could keep up the charade no longer and was coming out as a vegetarian. He did add, however, that his particular wing of vegetarianism regarded oxtail and oysters as honorary vegetables. A few weeks later he widened this dispensation to include pig's trotters, especially those in jelly. It always seemed rather a capricious diet to me — offal or tofu. In any case it proved too much for my mother, who skilfully put an end to any further septuagenarian silliness by serving him a dish of baked turnip stuffed with semolina.

I thought of him the other week in France, when I spotted tripe a la mode on a menu. Sadly, on ordering, I was told by a doleful waiter, 'Alas, monsieur, we are a little low in the tripes today.' At least in France it isn't a rarity to see offal on a menu or indeed in the supermarkets, whereas in these days of sanitised prepackaged meat it is virtually impossible to find decent offal in England. Even chickens don't come with their giblets any more.

Since sampling his sublime homemade sausages I've been cultivating our local butcher, and I got terribly excited when I saw a tray of pig's trotters in his window. I bought four — at 30p each — although I wasn't quite sure what I was going to do with them. My wife finally agreed to pop them into some cassou let she had spent the best part of a week preparing, but confessed to finding them rather grim to handle. And this from a girl whose mum boils pigs' heads for brawn!

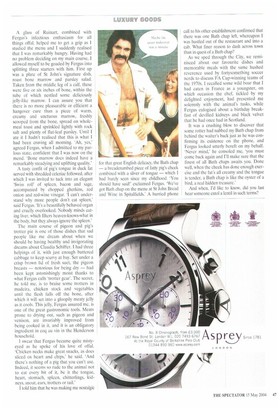

Apart from at my in-laws, I have yet to find a better place for offal than the Smithfield restaurant St John. co-owned by the guru of nose-to-tail eating, Fergus Henderson, whom I joined for lunch last week. I suppose that a throbbing hangover is not the most sensible of conditions in which to approach a meal consisting of extreme examples of offal — a word which refers to the organs and extremities of a beast — and I did rather regret my kiimmel-swilling of the previous night. The sight of two dead sucking pigs in the open kitchen, lying pale and waxy on the slab, their stomachs slit open ready to receive a serious stuffing, did stop me briefly in my tracks, as did Fergus's whispered promise, 'We have rather a nice bit of pig's spleen up our sleeve for the first course.'

A glass of Ruinart, combined with Fergus's infectious enthusiasm for all things offal, helped me to get a grip as I studied the menu and I suddenly realised that I was remarkably hungry. Having had no problem deciding on my main course, I allowed myself to be goaded by Fergus into splitting three starters with him. First up was a plate of St John's signature dish. roast bone marrow and parsley salad. Taken from the middle leg of a calf, these were five or six inches of bone, within the tube of which nestled some deliciously jelly-like marrow. I can assure you that there is no more pleasurable or efficient a hangover cure than a piece of warm, creamy and unctuous marrow, freshly scooped from the bone, spread on wholemeal toast and sprinkled lightly with rock salt and plenty of flat-leaf parsley. Until I ate it I hadn't realised that this is what I had been craving all morning. `Ah, yes,' agreed Fergus, when I admitted to my parlous state. confident that I was now on the mend. 'Bone marrow does indeed have a remarkably steadying and uplifting quality.'

A tasty confit of pig's tongue in duck fat served with shredded celeriac followed, after which I was invited to tuck into an elegant 'Swiss roll' of spleen, bacon and sage, accompanied by chopped gherkins, red onion and red-wine vinegar. 'I can't understand why more people don't eat spleen,' said Fergus. It's a beautifully behaved organ and cruelly overlooked. Nobody minds eating liver, which filters heaven-knows-what in the body, but they always ignore the spleen.'

The main course of pigeon and pig's trotter pie is one of those dishes that sad people like me dream about when we should be having healthy and invigorating dreams about Claudia Schiffer. I had three helpings of it, with just enough buttered cabbage to keep scurvy at bay. Set under a crisp brown lid of fresh suet, the pigeon breasts — notorious for being dry — had been kept astonishingly moist thanks to what Fergus calls 'trotter gear'. The secret, he told me, is to braise some trotters in madeira, chicken stock and vegetables until the flesh falls off the bone, after which it will set into a gloopily meaty jelly as it cools. This jelly, Fergus assured me, is one of the great gastronomic tools. Meats prone to drying out, such as pigeon and venison, are invariably improved from being cooked in it, and it is an obligatory ingredient in coq au yin in the Henderson household.

I swear that Fergus became quite mistyeyed as he spoke of his love of offal. 'Chicken necks make great snacks, as does sliced ox heart and chips,' he said. `And there's nothing of a pig that you can't use. Indeed, it seems so rude to the animal not to eat every bit of it, be it the tongue, heart, stomach, spleen, chitterlings, kidneys, snout, ears, trotters or tail.'

I told him that he was making me nostalgic for that great English delicacy, the Bath chap — a breadcrumbed piece of fatty pig's cheek combined with a sliver of tongue — which I had barely seen since my childhood. `You should have said!' exclaimed Fergus. 'We've got Bath chap on the menu at St John Bread and Wine in Spitalfields.' A hurried phone call to his other establishment confirmed that there was one Bath chap left, whereupon I was hustled out of the restaurant and into a cab. What finer reason to dash across town than in quest of a Bath chap?

As we sped through the City, we reminisced about our favourite dishes and memorable meals with the same hushed reverence used by fortysomething soccer nerds to discuss FA Cup-winning teams of the 1970s. I recalled some wild boar that I had eaten in France as a youngster, on which occasion the chef, tickled by my delighted enjoyment, had presented me solemnly with the animal's tusks. while Fergus eulogised about a birthday breakfast of devilled kidneys and black velvet that he had once had in Scotland.

It was a crushing blow to discover that some rotter had nabbed my Bath chap from behind the waiter's back just as he was confirming its existence on the phone, and Fergus looked utterly bereft on my behalf. 'Never mind,' he consoled me, 'you must come back again and I'll make sure that the finest of all Bath chaps awaits you. Done well, when the cheek has done enough exercise and the fat's all creamy and the tongue is tender, a Bath chap is like the oyster of a bird, a real hidden treasure.* And when. I'd like to know, did you last hear someone extol a lentil in such terms?

Previous page

Previous page