MENDELSSOHNS " PAUL."

THE great attraction of the Liverpool Festival was MENDELS- SOH ses new oratorio, Paul. The production of an oratorio is the highest ambition, as it is the proudest achievement, of the musi- cian : in proportion as his effort is daring, so is his failure or suc- cess conspicuous ; many adventurers having sunk under the bur- den they have vainly essayed to sustain, while only few have encountered themes of unequalled sublimity and grandeur fear- lessly and triumphantly. When concerned with common and every-day subjects, HANDEL was often mean and dull ; but when the theme was the stupendous deliverance of Israel, " he girt his harness round about him," and showed that this, of all others, was the fit exercise for his powers. Every oratorio-writer who can lay claim to the distinction of great, has diplayed not only origi- nality of thought, but of design—he has not followed in the track of any other master: BACH, HANDEL, GRAUN, HAYDN, BEET. HOVEN, SPOHR, each speak a language as distinct as SHAKSPEARE, MILTON, DRYDEN, POPE, and BYRON. Such writers scarcely possess the power to copy ; their works are the necessary and per- fect transcript of their own minds, and could not assume any other form than that in which they exist. Each of these has had his imitators and disciples : HANDEL had his SMITH and his WOK- GAN—both, like himself, oratorio-writers ; and in our own time HAYDN has his NEUKOMM, and BEETHOVEN his RIES. These followers, it is true, possess themselves of all the implements of their several masters ; they obtain the canvas, the easel, the colours; but where is the soul which imparts to that canvas life and thought and being ? where the heaven that beams from the eye, the grace and majesty which rest upon the brow ? where the Promethean touch that gives spirit and existence to clay ? Alas, for these we seek in vain !

MENDELSSOHN has thought fit, needlessly, as we Opine, to write his oratorio upon a model; needlessly, because it argues a distrust in his own powers, which we regard as equal to the forma- tion of a style of his own. Nor do we think it wise in him or in any writer to endeavour to put back the band of the musical clock, and strive to become one of the past century. The endeavour is usually unsuccessful. We live in a time in which music has assumed a more diversified character ; and it is impossible to get rid of the impressions which modern compositions engender : they start up in spite of ourselves, and involuntarily betray the date of a recent work. For this reason, all modern attempts to imitate the writing of the Elizabethan age, whether in prose, poetry, or music, are full of incongruities. The modern writer cannot live and think and write like him of ages gone by. He is the inhabi- tant of another region—of another atmosphere ; and the language of that period, then the natural language, is to him a foreign, if not a dead one. He writes in it, but not with graceful ease: his style is formal, stiff, constrained. He must bethink himself at every sentence, "Have I admitted a word or a phrase which will betray me ? have I been guilty of any modern heresy, or been betrayed into any recent innovation ?" Every modern writer, too, who sets before him the great works of antiquity as models from which he is not at liberty to depart, challenges a comparison with them by that very act. He says in effect, " Measure me against BACH and HANDEL; I have written as they write ; weigh me in the balance and see if I be wanting." This is a bold step to take, and it is one from which HAYDN shrunk.

In using the term " modern" as distinguished from " ancient," in relation to the style of music now under our notice, we must not be supposed to mean any thing which approaches to the orna- mental and florid, much less to the dramatic style. SPOHR'S sacred music is strictly modern, but it never deviates into the ornamental, still less into the frivolous.

Having said thus much, we add, without the smallest hesitation, that MENDELSSOHN has succeeded as well as, probably better than any living writer, in the attempt he has recently made. Having adopted a principle, he has rigidly and consistently ad- hered to it ; never suffering himself to be betrayed into any " wanton ease " or graceful negligence. " Simplicity," as we ob- served some weeks since, "is the pervading feature of his oratorio;' it is the pure musical Doric, with never the intrusion of a Corin- thian ornament.

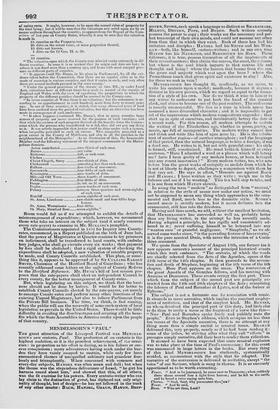

We quote from the Spectator of August 13th, our former (as it now appears accurate) account of the principal historical events which this work embraces. "The oratorio, of which the words are chiefly selected from the Acts of the Apostles, opens at the 24th verse of the 14th chapter. It then proceeds to the accusa- tion and death of Stephen, beginning at the 8th verse of the 6th chapter. Here Paul appears on the scene. The conversion of the great Apostle of the Gentiles follows, and his meeting with Ananias at Damascus. These events occupy the first part. Those which form the subject of the second part are principally ex- tracted from the 14th and 20th chapters of the Acts ; comprising the labours of Paul and Barnabas at Lystra, and of the former at Ephesus." The subject is not a fortunate one fur association with music. It abounds in mere narrative, which implies the constant employ- ment of recitative, and that of the simplest kind. Mr. BENNET, on whom devolved the principal part of this duty, had little else to do than to recite a verse or the fragment of a verse like this- " Now Paul and Barnabas spake freely and publicly unto the people." Even in Stephen's address, which occupies no less than ten verses of the Apostolic narrative, there is no attempt at any thing more than a simple recital in musical tones. Basussi delivered this, very properly, nearly as if he had been reading it : some of the ladies, by striving after what they call " effects " in passages simply narrative, did their best to render them ridiculous. It seemed to have been expected that some musical explosion was to take place at the time of Paul's conversion ; for this event was announced in large letters in the books. But every thing of this kind MENDELSSOHN has studiously, systematically avoided, as inconsistent with the style that he adopted. The narrative of the conversion is delivered in recitative, except " the voice" of our Saviour, which is sung in chorus. It is so curiously apportioned as to be worth extracting. Tenor. " And as he journeyed, he came near to Damascus; when suddenly there shone around him a light from heaven; and he fell to the earth, and he beard a voice saying unto him, Chorus. " Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou:ma? Tenor. " And he said, Bass. " Who art thou, Lord ? Tenor. "And the Loid said, Chorus. "I am Jesus of Nazareth, whom thou persecutest. Tenor. " And he said, trembling and astonished, Bass. " Lord, what wilt thou have me do? Tenor. " And the Lord said unto him, Chorus. " Arise, go into the city, and there shall it be told tb.ee what thou

must do."

Throughout the oratorio, the only principal voice part of' the least consequence is that of Paul : there are but one tenor, one alto, and two treble songs. The latter are all simple and unpre- tending; and even the part of Paul is by no means ambitious of effect or pregnant with melody. To quote again from our former brief account of the oratorio, " Its strength will be found to reside in its choruses, among which are many excellent speci- mens of fugal counterpoint. It does not assume a dramatic form, and is interspersed with frequent chorales, in confirmity with the

,model on which it is written.

The choruses, in truth, are masterly. In our notice of NEU- itomm's David last year, we remarked, that if lie began his cho- ruses at the church, they usually ended at the theatre. Nothing of this sort appears in Paul. MENDELSSOHN has here studied the great masters of his own country both profoundly and profit- ably. Every thing here is in keeping : he never wanders about feebly or ignorantly, never fritters away the broad outline of his subject ; all is clear, consistent, and majestic. That he reaches the colossal grandeur of his models cannot be affirmed. We see sometimes marked in a picture catalogue "after Rubens," or " after Corregio :" so is Paul " after Bach " and "after Handel;" but it is neither BACH nor HANDEL.

One of the most striking choruses is " Steiniget ihn !" (" Stone him to death !") The chorales are exceedingly beautiful ; as is the chorus " Seyd uns gniidig hohe Gaffer r (" 0 be gracious, ye immortals !"). "Sehet, welch' eine Liebe!' (" See what love !") is also deserving of high commendation.

We fear that Paul will not be a popular oratorio in this country. A succession of choruses, relieved chiefly by recitatives or songs for a bass voice, and necessarily sung by the same person, can scarcely be expected to prove attractive to a general audience. On those who heard it at Liverpool, it evidently excited little emotion of any kind : notwithstanding every predisposition to admire and applaud, only one piece was encored. Its hue is decidedly sombre. Of the pieces in the first act, one half are in the minor mood. The ear expects throughout something more in the way of relief;

but it expects in vain. The 1 e formanee, for a first performance, deserves high com-

mendation. The Liverpool chorus-singers are in excellent training ; and, considering the disadvantage under which they laboured, of having seen great part of the music only a few days before the Festival, it was executed with extraordinary correctness. To sup- pose that so short a preparation and a single rehearsal was suffi- cient to do justice to such a work, is to outrage common sense. Those who are acquainted with it, know that many beauties were but imperfectly developed, because imperfectly understood. This is no impeachment of the zeal or talent of the performers, but the mere dictate of plain experience. If it required repeated and laborious efforts in the Philharmonic band to give full effect to a single sinfonia, nothing short of a miracle could produce a per- fect exhibition of an entire oratorio from performers of a mixed character and congregated from various parts of the kingdom for the first time. " I have not studied my part," said a young vocal coxcomb to BARTLEMAN, " for I can sing it at sight." " True," replied BARTLEMAN, " if you call that singing." The rebuke of the accomplished artist applies with equal propriety to the ill-timed vaunt about performing an oratorio at sight. What Paul has especially to fear, is the indiscreet commenda- tion and unqualified panegyric of pretended friends. The compo- sition itself and the performance of it at Liverpool are praised with equal and indiscriminate zeal. Nothing could be more sub- lime than the one, nothing more perfect than the other. If both these assertions were true, how are we to account for the total absence of emotion on the part of those who heard it ? That it is not merely by clapping and shouting that the sympathy of an audience is expressed, was abundantly evident at Worcester during the performance of a part of the Last Judgment. The homage to genius was then involuntary and irresistible ; and the marked apathy at Liverpool is in part attributable to the want of that which can alone give refinement and polish to any work of art— repeated and laborious effort. Similar commendation was heaped on NEUKOMM'S David at Birmingham. Our estimation of this oratorio was regarded as severe, because we pointed out its defects as well as its excellencies, and hesitated to rank it, like its pro- fessed admirers, "with any similar production of HANDEL or Haynie." What is the result of all this foolish panegyric ?—Ab- solute extinction and oblivion. Two years have now elapsed, and nothing has been heard of David since the day of its first per- formance.

We fear the fate that awaits Paul in this country is dissection and mutilation • a song here and a chorus there will be extracted, for the sake of making a line in an oratorio bill. This is not the remedy for its defects, which are those of omission ; it requires something to be added, not taken away. And this it is easily in the author's power to effect ; for some of the most interesting events of Paul's life, and some of his most eloquent addresses, (the speech at Athens, for example,) form no part of the present selection from Luke's narrative. Judicials additions would give it the best chance of obtaining popularity in England.

Previous page

Previous page