The Fields of the Wood

Roy Kerridge

Cherokee County, North Carolina will not give sleep to mine eyes, or 1 slumber to mine eyelids, Until I find out a place for the Lord, an habitation for the mighty God of Jacob. Lo, we heard of it at Ephratah; we found it in the Fields of the Wood.' (Psalm 132, 4-6).

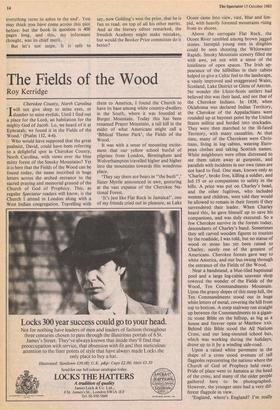

Who would have supposed that the great psalmist, David, could have been referring to a delightful spot in Cherokee County, North Carolina, with views over the blue misty forest of the Smoky Mountains? Yet it is here that the Fields of the Wood can be found today, the name inscribed in huge letters across the arched entrance to the sacred praying and memorial ground of the Church of God of Prophecy. This, as regular Spectator readers will know, is the Church I attend in London along with a West Indian congregation. Travelling with

them to America, I found the Church to have its base among white country-dwellers in the South, where it was founded at Burger Mountain. Today this has been renamed Prayer Mountain, a tall hill in the midst of what Americans might call a 'Biblical Theme Park', the Fields of the Wood.

It was with a sense of mounting excite- ment that our yellow school bus ful of pilgrims from London, Birmingham and Wolverhampton travelled higher and higher into the mountains towards this wondrous place.

'They say there are bears in "the bush",' Sister Myrtle announced in awe, gesturing at the vast expanse of the Cherokee Na- tional Forest.

'It's just like Flat Rock in Jamaica!', one of my friends cried out in pleasure, as Lake Ocoee came into view, vast, blue and lim- pid, with heavily forested mountains rising from its shores.

Above the surrogate Flat Rock, the Ocoee River tumbled among brown jagged stones. Intrepid young men in dinghies could be seen shooting the Whitewater Rapids. Smoky Mountain scenery filled me with awe, yet not with a sense of the loneliness of open spaces. The Irish ap- pearance of the hillbillies in their cabins helped to give a Celtic feel to the landscape, a vastly improved and exaggerated Wales, Scotland, Lake District or Glens of Antrim. No wonder the Ulster-Scots settlers had believed this was their land, and not that of the Cherokee Indians. In 1838, when Oklahoma was declared Indian Territory, the Cherokee of the Appalachians were rounded up at bayonet point by the United States militia and herded into stockades. They were then marched to the ill-fated Territory, with many casualties. At that time, many of the Cherokees were Chris- tians, living in log cabins, wearing Euro- pean clothes and taking Scottish names. White neighbours were often distressed to see them taken away at gunpoint, and parallels with incidents in our own times are not hard to find. One man, known only as 'Charley', broke free, killing a soldier, and led 15 or so companions to safety in the hills. A price was put on Charley's head, and the other fugitives, who included women and children, were told they would be allowed to remain in their forests if they surrendered their leader. When Charley heard this, he gave himself up to save his companions, and was duly executed. So a few Cherokee survive in the forests today, descendants of Charley's band. Sometimes they sell carved wooden figures to tourists by the roadside, I was told, but no statue of wood or stone has yet been raised to Charley, surely one of the greatest of Americans. Cherokee forests gave way to white America, and our bus swung through the entrance of the Fields of the Wood.

Near a bandstand, a blue-tiled baptismal pool and a large log-cabin souvenir shop towered the wonder of the Fields of the Wood, Ten Commandments Mountain. Upon the grassy slopes of this steep hill, the Ten Commandments stood out in huge white letters of metal, covering the hill from top to bottom. A steep stairway ran straight up between the Commandments to a gigan- tic stone Bible on the hilltop, as big as a house and forever open at Matthew xxii. Behind this Bible stood the All Nations Cross, and our long-snouted school bus, which was working during the holidays, drove up to it by a winding side-road.

Upon a raised white pavement in the shape of a cross stood avenues of tall flagpoles representing the nations where the Church of God of Prophecy held sway. Pride of place went to Jamaica at the head of the cross, and many of the older people gathered here to be photographed. However, the younger ones had a very dif- ferent flagpole in view.

'England, where's England? I'm really looking forward to being photographed under England. Come on, only those born in England are allowed to be in the photo.'

'England's over here, but you weren't born there!'

Looking yearning and pathetic, a teenage girl who had been brought to Birmingham from Jamaica at the age of five turned away. Benignly the Jamaicans strolled back towards the English. I was the only white Englishman there, and the conversations that followed interested me.

'When I'm in England I call Jamaica "Home", but when I go back to Jamaica I sweat all the time, and my relatives there say I have to sit in a room till the ice thaws out of me,' the girl from Birmingham said. 'Then I mean "England" when 1 say "Home":

'We have so much Home,' her mother said, sighing.

'Yes, till we find our real Home,' a friend chimed in, looking at the clouds beyond. Ten Commandments Mountain.

Suddenly noticing me, this friend, a middle-aged woman, ran up and hugged me as if seeing me for the first time.

'Are you really a full-blooded Englishman? 0, praise the Lordl '

One of the unofficial prophecies believed in by the English-West Indian members of the Church of God of Prophecy is that West Indians have come to England to lead the erring British back to God. Many West Indians of other denominations believe this also, and in my case there is some truth in the matter, as I loved negro spirituals long before I came to care for their subject. In Tennessee and North Carolina my West In- dian companions slipped easily into American negro life, which led some of them to argue that there was a brotherhood of colour beyond that of nation. When, at a church meeting, an African declared that they were all Africans, they applauded in delight.

Perched on top of Matthew xxii, for the Bible had a door and steps at the back, we enjoyed a fine view of the mountains. On Prayer Mountain, the hilltop where A.J. Tomlinson had the vision that was to found the Church, a white monument had been raised. Many members of my party used it as a Wailing Wall, kneeling with their foreheads resting on the stone, crying and sobbing out their devotions.

A few days later, when the rest of the delegates arrived for the General Assembly in Cleveland, Tennessee, the Fields of the Wood presented a bank holiday ap- pearance, swarmed over by thousands. Most of the crowds were white Southerners, together with West Indians from every part of the Caribbean. Highlight of the occasion was the Bahama Brass Band, who marched in single file up and down the various steps blowing lustily. All were clad in gorgeous red uniforms and their leader wore the full dress of a colonial governor, with plumed hat and sword. New Orleans jazz is said to have evolved from religious brass band pro- cessions, and in the Bahama Band this pro- cess seems to have begun anew. Hillbilly singers strummed sacred songs on the band- stand, and all the way up to the peak of Prayer Mountain a preacher stood at each of the marker stones, engraved with texts, that lined the way, and roared out an in- dividual message. A blasted pine, the Witness Tree, had a sign on it that told of the day when lightning scored the whole trunk down to the roots, yet jumped two feet to spare the church flag that hung there. Near here I met an affable mining engineer from West Virginia, who said he had trained many British miners to work in the Appalachian coalfields. His ancestors were O'Neills from Ulster, he told me, but when I began a potted biography of Shane O'Neill his attention wandered.

am full, Brother! I have had spiritual T-bone steak!' one of the Sisters informed me, Surfeited, we returned to Cleveland.

'T et us all behave in a proper English fashion,' Pastor McCalla said ner- vously next day, as we rehearsed a gospel song at our hotel.

Every nation represented had to perform a party piece in the middle of the Taber- nacle, the church auditorium. Never before, since the general assemblies had begun, had a white man taken part in the English procession. It appeared that the remarkably incurious white Southerners blandly took it for granted that England was a wholly negro nation. It seemed a pity to disillusion them, but all attempts on my part to escape were swept aside. At gospel singing practice, however, I was allowed to open and shut my mouth noiselessly.

To triumphant music from the Bahama Brass Band, the English delegates marched into the Tabernacle, waving flags, with myself in the rear. Our gospel song went over well, and no one in the audience notic- ed that a chorus was omitted by mistake. It sounded beautiful, but I bit my lip and con- trolled myself. If I had been carried away and joined in, there could have been an ugly rift in Anglo-American affairs, perhaps resulting in an international incident. As it was, England's reputation was unblemish- ed, and amid loud applause I marched back with the others to the foyer. Looking up, I caught the sneering and hard-boiled eyes of a very inbred-looking, half-squinting bunch of roughnecks from the backwoods. Most of the white Southerners and mid- Westerners were an agreeable peach-blond, Jimmy Carterish lot, however, and whooped and hollered with the best of them. Unheard of in England except among West Indians, the Church of God of Pro- phecy is much respected in Tennessee.

Feeling pleased with ourselves, we relax- ed and watched the disciplined march of the British Virgin Islanders, who wore white naval costumes and saluted smartly.

'All is well in the British Virgin Islands!' their captain reported. 'The crewmen are well armed and ready for battle. Sail on, Battleship Zion, for land is ahead and we the Caribbean crew will prevail! Destina- tion — the celestial world!'

Previous page

Previous page