Exhibitions

Whistler (Tate Gallery, till 8 January)

Touch ephemeral

Giles Auty

Whenever I consider the precise place James McNeill Whistler ought to occupy in the pantheon of painters, he floats off like the butterfly which he used, significantly perhaps, for his signature. Was he then merely a transitory titan, an evanescent evangelist for the future cause of abstrac- tion in art?

The joy of the present large survey of Whistler's work at the Tate Gallery, excel- lently put together in the main by the art critic for the Daily Telegraph, Richard Dor- ment, is that we can try at last to pin down Whistler and his influence on future gener- ations more accurately. The .exhibition is the biggest put together since Whistler's death more that 90 years ago. There are more than 200 works of all kinds ranging from large, polished portraits in oils to etchings and sketches.

The artist was born in Massachusetts 160 years ago and lived between the ages of nine and 14 in St Petersburg, where his father worked as an engineer for the Tsar. It was in this refined world that Whistler first studied drawing, at the Imperial Academy of Fine Art. There is little doubt that he prided himself on being different in background from his peers whether in France or Britain and, from perceiving himself thus, it was but a short step, per- haps, to seeing himself as something of a sage or provocateur. Yet I feel that genera- tions of art historians have taken Whistler's provocative utterances about art too literal- ly, in some cases because of their use to them as a prop for subsequent theory. When faith in modernist evolution was at Vrepuscule in Flesh Colour and Green: Valparaiso, by James Whistler, 1866 its highest, Whistler was grasped to the bosom of American theorists not only as a fellow countryman but as a forerunner of the formalist abstraction that flourished in the United States. In fact, there is much in Whistler that is invincibly European, both in lifestyle and in attitude.

The gifted but severely earnest American painter, Thomas Eakins, saw Whistler's art as morally retrograde because it left too much to the imagination. Comparing its often poetic vagueness with the almost heroic morality of what he considered great art, Eakins judged Whistler's output as 'a very cowardly way to paint.' The view is over extreme, yet I would submit there is an unsatisfying element in the thinness and vagueness of some of Whistler's work.

The paintings to which this does not apply are more monumental as a result. `Harmony in Grey and Green: Miss Cecily Alexander', 'Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter's Mother', `Symphony in White No.2: The Little White Girl' and 'Symphony in White No. 1: The White Girl' are essays in realism rather than illusion. Yet Courbet disliked the mystery and spiritual intensity of the latter as compromises of realistic integrity. But if Courbet had a point here what might he not have said about the riverscape 'Noc- turne: Grey and Silver' 1873-75 which approaches a thin, if poetic, tricksiness? Nor is this kind of technique far removed from that of 'Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket' 1875 in which the artist takes evanescence as a lyrical theme. This was, of course, the work which was responsible for John Ruskin's infamous utterance 'a pot of paint flung in the pub- lic's face' and Whistler's subsequent suing of him for libel. Sympathy has been largely with the plaintiff since then but Whistler was ruined nevertheless by the costs of the case and the derisory damages awarded. Much of what Whistler said at the time antic- ipated the later manifestos of modernism.

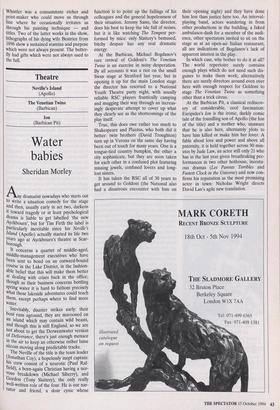

His desire to strip art of sentimental bag- gage and associations was admirable but formalism itself — the seeing of art simplY as arrangements of shapes and hues — 15 hardly less dangerous for the unwary. Whistler seems to me to have been close to his best where the formal and atmospheric elements were hung on hooks of solid per- ception. No work sums this aspect up bet- ter than `Crepuscule in Flesh Colour and Green: Valparaiso' 1866 which has been one of my lifelong favourites. 'Violet and Silver: A Deep Sea' which belongs to the Art Institute of Chicago is an exuberant late work, painted on a hot summer's day in Britanny in 1893, a boatman reputedly steadied the artist's craft while he executed this little masterpiece off-shore. In spite of great natural gifts, Whistler's life was a boat that often needed steadying. Yet the skeletal solidity that underlay even his more evanescent oil paintings had its roots in exceptional powers of draughtsmanship. Whistler was a consummate etcher and print-maker who could move us through line where he occasionally irritates us through his painting technique — and titles. Two of the latter works in the show, lithographs of his dying wife Beatrice from 1896 show a sustained stamina and purpose which were not always present. The butter- fly had gifts which were not always used to the full.

Previous page

Previous page