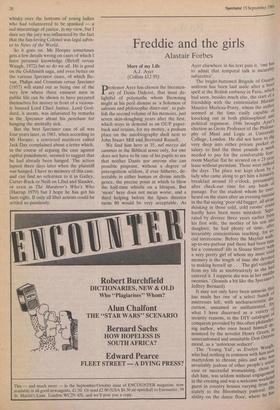

Freddie and the girls

Alastair Forbes

More of my Life A.J. Ayer (Collins £12.95)

Professor Ayer has chosen the bicenten- ary of Denis Diderot, that most de- lightful of polymaths whom Browning might at his peril dismiss as 'a Solomon of saloons and philosophic diner-out', to pub- lish the second volume of his memoirs, just seven skin-sloughing years after the first, which stays in demand as an OUP paper- back and retains, for my money, a podium place on the autobiography shelf next to John Stuart Mill and Bertrand Russell.

We find him here at 35, nel mezzo del cammin in the Biblical sense only, for one does not have to be one of his pupils to see that neither Dante nor anyone else can possible pinpoint, without a degree of precognition seldom, if ever hitherto, de- tectable in either human or divine intelli- gence, the precise point at which to blow the half-time whistle on a lifespan. But 'more' here does not mean worse, and a third helping before the Spurs director turns 80 would be very acceptable. As

Ayer elsewhere in his text puts it, 'one has to admit that temporal talk is incurably subjective'.

The bright-buttoned Brigade of Guards uniform has been laid aside after a brief spell at the British embassy in Paris, which had seen, besides much else, the start of a friendship with the existentialist Marxist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whom the author seemed at the time easily capable of knocking out in both philosophical and political argument. 1946 brought Ayer 'a election as Grote Professor of the Philoso- phy of Mind and Logic at University College, London. He did not have to dig very deep into either private pocket or salary to find the three pounds a week needed to pay for the comfortable four' room Mayfair flat he secured on a 21-year lease without premium. Those were indeed the days. The place was kept clean by a lady who came along to get him a leisurely breakfast around 10 o'clock, presumably after check-out time for any birds of passage. For the student whom he over- heard on the stairs after an evening tutorial in the flat saying 'poor old bugger, all alon. thinking in those cold, cold rooms' conic' hardly have been more mistaken. Sella- rated by divorce three years earlier fr°a/ his first wife, the mother of his son and daughter, he had plenty of time, after invariably conscientious teaching, for s,;),- cial intercourse. Before the Mayfair waus. up-to-my-parlour pad there had been time for a 'contented' life in Sloane Street a very pretty girl of whom my most vivid memory is the length of time she devoted to making herself up . . . The girl vanished from my life as unobtrusively as she ,h,le a entered it. I suppose she was in her miuu,.. twenties.' (Sounds a bit like the Spectator Jeffrey Bernard). It may not only have been amnesia al has made her one of a select bunch ° mistresses left, with uncharacteristic dis- cretion, cretion, unnamed or unillustrated, for what I have discerned as a variety security reasons, in the DIY catalogue ° conquests provided by this often philander- ing author, who once heard himself de- nounced by the novelist Henry Greela'.„0 unaccustomed and unsuitable Don Otto" mood, as a 'notorious seducer'. h, The 'Young Yid', as Evelyn Wali've who had nothing in common with him sa martyrdom to chronic piles and who was invariably jealous of other people's snel_ ease or successful womanising, chose Lout dub him, was seldom without engager d ken in the evening and was a welcome wee- the guest in country houses varying from His stately to the Bloomsbury pastoral. ns ability on the dance floor, where he "" always been a tireless performer, together with his lacertilian appearance, made him an almost archetypal 'lounge lizard'. At Mottisfont he was rightly impressed by the range of Raymond Mortimer's knowledge and by the trouble he took over his remarkable book reviews, but he perhaps delighted more in the company of that virile heterosexual sportsman, Clive Bell. His social acceptability was matched by his skill at competitive games, particularly tennis.

The first of many teaching visits to the United States was to be the autumn semes- ter at New York University. The head of the philosophy department there was Sid- ney Hook, whose pragmatism, like the author's, was, some years later, to be put to stern practical test when they had to share a bed at Jefferson University of Virginia at Charlottesville. Nigel Dennis is the best remembered of his NYU pupils. Like some of my randy Puritan ancestors in 17th-century New England, when one of his women was 'shot from under him', Freddie Ayer would simply send for a replacement from England. One of these Was Angelica Wheldon whose beauty was before long to prove suicidally fatal both to herself and to another lover more sen- timentally engage than the professor, who attaches to himself the label `emotivist' Only in a strictly philosophical sense. In Houston, Texas, he became some- tiling of an addict of a local tipple called suzerac 'a happy mixture of Bourbon whisky, Pernod, syrup, bitters and lemon'. Never abstemious, he equally happily re- calls getting incoherently tipsy on the air with his friend and debating opponent Father Corbishly of Heythrop College, all Improbably done on excessive studio hos- pitality from BBC Wales. The trouble about any attempt by lay persons to follow the work of philo- sophers is their tendency in each successive Work to refute or dismiss what they have set out at length in previous dissertations, and the present book is no exception. This is disarmingly honest and modest but Perhaps also rather time-wasting for those ;if us not in the academic racket ourselves. 1.„, greatly sympathised with the late !"(aiinund von Hofmannsthal and his beautiful and much missed Paget wife Liz which for a period she was indeed very often to be found, there is a characteristi- cally fetching photograph included) when I _oUnd them one day sitting stunned with incomprehension at the copy before them u2_ The Origins of Pragmatism, the damn- dest, thickest, squarest book of the entire hose oeuvre and the one he had just

_n to dedicate to them jointly.

circlesIles' he frequented 'interlocked at many _rouns'. More than Bergotte-Bergson in Proust Isaiah Berlin in Washington or cl,nny Quinton in his wildest dreams, Fred- le Ayer was not only the best philosopher 'host hostesses had got, he was also the

only one a lot of girls, some of them memorably pretty and clever too, seemed to want to capture or be captured by.

Since Part of my Life, he seems in this field to have been probing a bit deeper for self-knowledge, discovering, for example, that he is drawn to some women by a kind of vicarious, proxy lure, the dropping of names preceding, as it were, the dropping of trousers. The French have an expression

for that — y a des noms qui font bander'. Pretty Polly Peabody's attrac- tions, for instance, were, he tells us, enhanced by her having as parents the Crosbys, 'a legendary couple in pre-war café society'. (He evidently didn't know about Caresse Crosby's invention of the brassiere, a more resonant Twenties event even than her husband's headlined suicide in a Boston hotel). The principal come-on of Pam Peniakov bizarrely seems to have been the fame of her husband's wartime desert exploits commanding Popski's pri- vate army.

An appetising photograph is included of the rather androgynous Australian head of Jocelyn Rickards, of whose long and happy relationship with the author I used to catch glimpses from a window in the same square. Jocelyn disapproved of his first taking up with and then marrying Dee Wells (whose partly aggressive, partly puz- zled American personality swamped the British media scene for many years), 'not out of jealousy, but because she did not think us suited to one another'. I don't think I thought so either, and might well have thought so even less had I known, as I now do from this book, that Dee had once risen to the rank of Sergeant-Major in the Canadian army. But it is quite true, as the author says on the concluding page, that his love for their son Nicholas has been a dominating factor in his life since his birth in 1963. He has also always struck me as being a notably admirable, affectionate and unselfish step-father.

Graham Greene, whom he puts 'first among living English novelists,' once in- vited him 'to see if my rational arguments could undermine his faith, and we actually embarked on the experiment which I prob- ably took more seriously than he did; at least he very soon showed that he did not want it to continue'. I can myself recall reacting similarly, and feeling obliged to bail out cravenly from a London taxi I was sharing with • Freddie at a time when Hitler's capriciously-targeted V-weapon offensive was coinciding with one of my own intermittent but intense bouts of Christian belief: Back then to good old Diderot who observed that 'If Reason is a gift of Heaven and the same is to be said about Faith, then Heaven has made us two incompatible and contradictory presents'.

It is hard to see why Freddie's tip-of-the- tongue answer on the famous BBC Brains Trust to the question 'Do you believe in the Devil', 'No, nor in God either' should have provoked such a storm of abuse and hate-mail from professed Christians, in- cluding an attempt by Frank Longford to have him banned from the airwaves altogether. But like Pakenham, he 'en- joyed the publicity' these programmes brought him, while he seems to have avoided the fault he sees in Muggeridge of having allowed 'his prominence on televi- sion to aggrandise his self-esteem', as well as always eschewing the put-down or per- sonal abuse.

Another 'Freddie', Queen Frederica of Greece, whom he fails to have spotted as the Last Attachment of that amateurish Afrikaaner Gestalt philosopher Field- Marshal Smuts, seems to have flirted both with him and the idea of becoming Cather- ine the Great to his Diderot, or Frederick the Great to his Voltaire, but she was not a good listener and nothing came of it. In Washington's 'Camelot' days, Ethel Ken- nedy proved an equally impatient listener, and her inept and irrelevant interruptions on Thomist themes had to be squashed by her Attorney-General husband Bobby with a brisk 'Can it, Ethel!' (not 'Drop it!' as Ayer has for some reason anglicised it).

For one whose philosophical themes have so largely rested on verifiability, Ayer has been surprisingly slipshod in letting through far too many errors of fact or memory, which seems a pity, though I have no space to list them. His publishers must take the blame for fashionably feckless 'editing and for farming out the indexing to someone clearly not up to this taxonomic task, the result resembling both by its inclusions and exclusions the absurdities of present-day Court Page cast lists in the Times and Telegraph. The author's ageing `Regency' Buck chum, the chatelain of Longleat, may be amused to find himself promoted to the Dukedom of Bath, to match his son-in-law's of Beaufort, but a whole group of home and foreign intellec- tuals mentioned in the text are wiped out from the surviving sottisier of incorrect academic and social styles and titles. This lapse should, however, put nobody off enjoying this work by an author who, as Isis once wrote in a comparison between his lectures and Isaiah Berlin's amongst others, 'gives uniquely good value'.

Previous page

Previous page