Sugar

John Braine

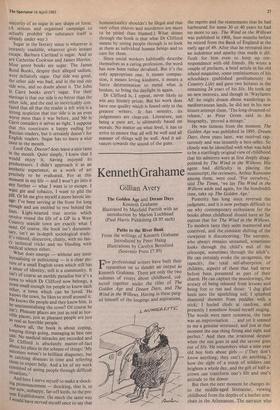

Look Out, Doctor! Dr Robert Clifford (Pelham Books £7.95)

'What signifies,' says someone, 'giving halfpence to common beggars? TheY only lay it out in gin and tobacco.' And why should they be denied such sweeteners of their existence?' says Johnson, 'It is sure- ly very savage to refuse them every possible avenue to pleasure, reckoned too coarse for our own acceptance. Life is a pill which none of us can bear to swallow without gilding . Or, in the worlds of the Mary PoPPins song, just a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. (Incidentally, how rntiell more I preferred Julie Andrews fully dress- ed singing marvellous songs to charmirtg children to Julie Andrews bare-breasted. in black comedy surrounded by raving psychopaths!)

The sort of people who in Johnson's day would have denied beggars tobacco and gin are still with us. But now it's not just a mat' ter of tobacco and gin. Our new, unhaPPY' far-off lords would really like to deny the majority of us sugar in any shape or form. (A serious and organised campaign to actually prohibit the substance itself is already under way.) Sugar in the literary sense is whatever is instantly readable, whatever gives instant escape. Barbara Cartland is sugar. And so are Catherine Cookson and James Herriot. Most genre books are sugar. The James Bond Books, despite their alleged sadism, were definitely sugar. Our side was good, the other side was bad, and in the end our side won, and no doubt about it. The John le Carr& books aren't sugar. For their message is that our side is no better than the Other side, and the end so inextricably con- fused that all that the reader is left with is a strong suspicion that our side is in an even worse mess than it was before, and Mr le Carre considers it serves us right. I suppose that this constitutes a happy ending for Russian readers, but it certainly doesn't for English readers. Sugar has to leave a nice taste in the mouth.

Look Out, Doctor! does leave a nice taste in the mouth. Quite simply, I knew that I would enjoy it, having enjoyed its Predecessors. I didn't approach it as an aesthetic experience, as a work of art Precisely to be evaluated. For at this Moment in my life — and I won't go into it any further — what I want is to escape. I want gin and tobacco, t want to gild the Pill. Or let me give myself a more heroic im- age: I've been serving at the front for long enough and am entitled to rest behind the lines. Light-hearted true stories which revolve round the life of a GP in a West Country seaside town are exactly what I need. Of course, the book isn't documen- tary, isn't an in-depth sociological study. It's relaxed, discursive, chatty, with no fan- cy technical tricks and no blinding with medical science either. What does emerge — without any intel- lectualising or politicising — is a clear pic- ture of a small English town which still has a sense of identity, still is a community. It isn't of course an earthly paradise but it's a town to which Dr Clifford now belongs, a town small enough for people to know each (3, ther, a town which can be 'loved. He Knows the town, he likes to stroll around it. He knows the people and they know him. Is he sentimentalising the town? Of course he isn't. Pleasant places are just as real as hor- rible places, just as pleasant people are just as real as horrible people. Above all, the book is about coping, keeping things going, managing as best one an. No medical miracles are recorded and Dr Clifford is absolutely matter-of-fact about his place in the scheme of things: `My isuceesses weren't in brilliant diagnoses, but tn catching diseases in time and referring chem to expert help. And a lot of my work onsisted of seeing people through difficult situations.'

And here I nerve myself to make a shock- lng pronouncement — shocking, that is, to o sur new, unhappy, far-off lords, to the pre- _ent Establishment. (In much the same way I would have nerved myself once to say that

homosexuality shouldn't be illegal and that very often thieves and murderers are more to be pitied than blamed.) What shines through the book is that what Dr Clifford means by seeing people through is to look at them as individual human beings and to care for them.

Since social workers habitually describe themselves as a caring profession, the word has now been rather devalued. But it's the only appropriate one. It means compas- sion, it means loving kindness, it means a fierce determination to mend what is broken, to bring the daylight in again.

Dr Clifford is, I repeat, never likely to win any literary prizes. But his work does have one quality which is found only in the greatest writers. It has serenity, its judgements are clear-cut. Literature, not being a pure art, is ultimately based on morals. No matter on what level, it has to strive to ensure that all will be well and all manner of things will be well. And it ad- vances towards the sound of the guns.

Previous page

Previous page