A monstrous betrayal

Alexander Chancellor

About the feelings of the Palestinian Arabs actually living under Israeli rule there was practically nothing to be read in the British press this week. Only Eric Silver of the Guardian, writing from Jerusalem, reported that there was 'widespread disap- pointment' in the occupied territories over the apparent collapse of President Reagan's peace plan. But the only reported comment by a Palestinian Arab, the deposed mayor of Gaza, was remarkably restrained: 'We had wished for another outcome. The pre- sent situation is a mistake.'

If I were a Palestinian Arab still living in Palestine, 1 would find the situation not so much a mistake as a disaster. For what sort of future is there for the Arab inhabitants of the West Bank and Gaza? On Monday the newspapers contained two reports with Chilling implications. One was the Jorda- nian Government's announcement that, deprived of the backing of the Palestine Liberation Organisation for negotiations with Israel, it was washing its hands of the Whole problem and would be 'compelled to adopt the measures necessary to protect its national security, in all its aspects, with em- phasis on national unity'. Jordan, in other Words, will steel itself to resist any further influx of refugees from the other side of the river which forms its boundary with Israeli- ruled territory. And on the other side of the river, what is going to happen? According to Christopher Walker of the Times, the Israeli Government is considering a plant() colonise the West Bank with such intensity that within 30 years there will be as many Jews living there as there will be Arabs, some 1.3 million of each race. At present about 30 times more Arabs than Jews are living there and they already seein quite frightened and angry enough.

,,

heY already believe that the Israelis want to drive them from their homes. How will they be feeling in a few years' time if this .new Plan is put into effect, its first stage be- ing to establish another 57 Jewish fortress towns among them? How many Arabs will then feel like staying on the West Bank? And if many of them want to run away, Where will they go? The refusal of the PLO to permit Jordan to negotiate with Israel on its behalf could mean the beginning of the end of any form Of Palestinian reality. It is a monstrous ,°etraYal of those who are still keeping the ho me fires burning. The residents of Nablus or Hebron or Jericho may be more comfortable and less pitiable than the Palestinians living in refugee camps abroad, but Without them the Palestinians' claim to a national home would be doomed. The Palestinian would become what the Jews used to be — scattered exiles dreaming of

Jerusalem. And in the case of the Jews, it took 2,000 years for the dream to come true.

During exasperating conversations with Palestinians in Jordan, I sometimes got the impression that they were reconciled to this pathetic role. For all the blood they have shed and deprivations they have suffered for their national cause, they persistently refuse to contemplate any steps which might actually help it to succeed. In their ef- forts to preserve a semblance of unity within their movement, they adopt public positions which play into Israel's hands, while privately saying whatever will endear them to their listeners. Even the man who is theoretically mayor of Hebron seems dur- ing his three years of exile to have grown strangely uninterested in the affairs of his home town. At least, he did not wish to discuss them with me. He wanted instead to persuade me that the main result of the Palestinian National Council meeting in Algiers had been acceptance of the Reagan plan, the precise opposite of the case.

Despite such things, King Hussein ap- parently believed that the pace of Israel's colonisation of the West Bank would final- ly concentrate the minds of the PLO. Defeated in battle, their only hope now was to attempt through negotiation to prevent the annexation by Israel of the rump of what they regard as the Palestinian homeland. It was obvious to everybody that time was running out, that with every new Jewish settlement on the West Bank, Mr Begin's dream of an enlarged Jewish state to include all the land which God rashly promised to Abraham was a step nearer reality. But in the end, the PLO remained true to itself and buried what may be the last Middle East peace plan with any chance of success.

The Palestinians could reasonably argue that its chance of success was always ex- ' tremely small, that Mr Reagan's idea of a 'self-governing Palestinian entity in the West Bank in association with Jordan', while not only unattractive to them in itself, was very unlikely ever to see the light of day. To begin with, there are no grounds for thinking that Mr Begin will ever volun- tarily abandon the biblical lands of Judaea and Samaria, or that the Jewish settlers there could be dislodged without the greatest difficulty. And secondly, it is dif- ficult to find any Arab who believes that the United States will ever put the necessary pressure on Israel to enforce some sort of reasonable settlement. Such scepticism is more than justified. Despite its frequent condemnations of Israel's colonisation of the West Bank and of its occupation of Lebanon, and despite the fact that Reagan's peace plan was on the point of collapse, the best that the United States would do last week was to say that it would try to persuade Israel to halt its settlement programme if King Hussein joined the peace talks. This was hardly reassuring. But these are not good enough reasons for the Palestinians letting Mr Begin have everything his own way. It could only have been to their advantage to call the Americans' bluff. The world would finally have been able to measure the degree of , America's commitment to a just solution of the Palestinian tragedy. It would also have' been able to assess the true nature of Israeli public opinion, for the occupation of the West Bank is a source of much unease and heart-searching in Israel. Relieved of the fear that the PLO is dedicated to Israel's destruction, many Israelis might be much readier to press for a reasonable com- promise. The Peace Now movement, Which was able to muster a demonstration of more than 400,000 people after the massacre in West Beirut last summer, is against the West Bank settlements, and many other Israelis are very doubtful if Israel could ab- sorb another million Arabs without dire consequences.

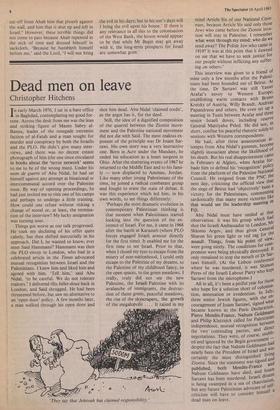

Nor does Mr Begin's biblical justification for his policy go unchallenged. A few weeks ago in Jerusalem, when I was attending a vigil outside the Knesset for a peace demonstrator killed by counter-protestors, 1 was rescued from a downpour by a retired army major carrying an umbrella. He told me in great earnestness that the reason why Israel must withdraw from the West Bank was to be found in the 21st chapter of the First Book of Kings. This tells the story of Naboth's vineyard. Ahab, the King of Samaria, wanted the vineyard to turn it into a herb garden, but Naboth refused either to sell it or to accept a better vineyard in ex- change 'for the Lord forbid it me that I should give the inheritance of my fathers unto thee'. Ahab then sulked so much that his wife Jezebel took matters into her own hands, got Naboth killed, and procured the vineyard. When the Lord heard about this, he told Ahab: 'I will bring evil upon thee, and will take away thy posterity, and will cut off from Ahab him that pisseth against the wall, and him that is shut up and left in Israel.' However, these terrible things did not come to pass because Ahab repented in the nick of time and dressed himself in sackcloth. 'Because he humbleth himself before me,' said the Lord, 'I will not bring the evil in his days; but in his son's days will I bring the evil upon his house.' If there is any relevance in all this to the colonisation of the West Bank, the lesson would appear to be that while Mr Begin may get away with it, the long-term prospects for Israel are somewhat grim.

Previous page

Previous page