Persuasion in pictures

Kevin Sharpe

THE KING'S BEDPOST: REFORMATION AND ICONOGRAPHY IN A TUDOR GROUP PORTRAIT by Margaret Aston Cambridge, £40, pp. 267

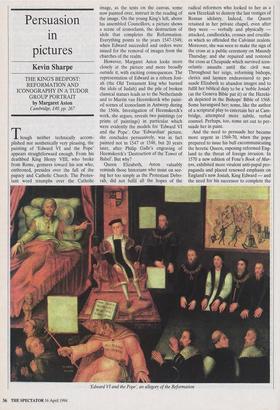

hough neither technically accom- plished nor aesthetically very pleasing, the painting of 'Edward VI and the Pope' appears straightforward enough. From his deathbed King Henry VIII, who broke from Rome, gestures toward his son who, enthroned, presides over the fall of the papacy and Catholic Church. The Protes- tant word triumphs over the Catholic image, as the texts on the canvas, some now painted over, instruct in the reading of the image. On the young King's left, above his assembled Councillors, a picture shows a scene of iconoclasm, the destruction of idols that completes the Reformation. Everything points to the years 1547-1549, when Edward succeeded and orders were issued for the removal of images from the churches of the realm.

However, Margaret Aston looks more closely at the picture and more broadly outside it, with exciting consequences. The representation of Edward as a reborn Josi- ah (the Old Testament king who burned the idols of Judah) and the pile of broken classical statues leads us to the Netherlands and to Martin van Heemskerck who paint- ed scenes of iconoclasm in Antwerp during the 1560s. Investigation of Heemskerck's work, she argues, reveals two paintings (or prints of paintings) in particular which were evidently the models for 'Edward VI and the Pope'. Our 'Edwardian' picture, she concludes persuasively, was in fact painted not in 1547 or 1548, but 20 years later, after Philip Galle's engraving of Heemskerck's 'Destruction of the Tower of Babel'. But why?

Queen Elizabeth, Aston valuably reminds those historians who insist on see- ing her too simply as the Protestant Debo- rah, did not fulfil all the hopes of the radical reformers who looked to her as a new Hezekiah to destroy the last vestiges of Roman idolatry. Indeed, the Queen retained in her private chapel, even after they were — verbally and physically attacked, candlesticks, crosses and crucifix- es which so offended the Calvinist zealots. Moreover, she was seen to make the sign of the cross at a public ceremony on Maundy Thursday; and she repaired and restored the cross at Cheapside which survived icon- oclastic assaults until the civil war. Throughout her reign, reforming bishops, clerics and laymen endeavoured to per- suade Elizabeth to abandon images and to fulfil her biblical duty to be a 'noble Josiah' (as the Geneva Bible put it) or the Hezeki- ah depicted in the Bishops' Bible of 1568. Some harangued her; some, like the author of a scriptural play to entertain her at Cam- bridge, attempted more subtle, verbal counsel. Perhaps, too, some set out to per- suade her in paint.

And the need to persuade her became more urgent in 1569-70, when the pope prepared to issue his bull excommunicating the heretic Queen, exposing reformed Eng- land to the threat of foreign invasion. In 1570 a new edition of Foxe's Book of Mar- tyrs, exhibited more virulent anti-papal pro- paganda and placed renewed emphasis on England's new Josiah, King Edward — and the need for his successor to complete the Edward VI and the Pope, an allegory o the Reformation overthrow of Antichrist. Foxe's illustrations drew on Dutch Calvinist painters, such as Marcus Gheeraerts the elder. And from the same circles, Aston ingeniously sug- gests, prints of Heemskerck's paintings came to England. For, in 1568, the human- ist Hadrianus Junius, whom Foxe had suc- ceeded as tutor to the Howard family's children, returned to England. In the Netherlands, Junius, a friend of Heemsker- ck, had often provided verses to the artist's work, and to engraved prints of his paint- ings executed by Philip Galle. It may then be that Junius brought with him to England in 1568 the models that made 'Edward VI and the Pope' into a powerful admonition to Queen Elizabeth — from her godly sub- jects at home and Dutch Calvinists abroad.

There is a final twist. For, in 1569, Junius' and Foxe's former charge, Thomas Howard, now Duke of Norfolk, was dab- bling with marriage to Maly Queen of Scots and in treasonous intrigue that was to end his life on the scaffold. Foxe wrote urgently to pull his old pupil from the precipice of self-destruction. Could, Aston asks, 'Edward VI and the Pope', with its reminder in the group of Councillors of old Howard enemies waiting to exploit the advantage, have been intended to warn Norfolk not to repeat the errors of his father, executed in 1547? Much more research, not least on the factional politics of the 1560s, would be needed to venture such an argument with confidence; but whether to Norfolk, or, more persuasively, Elizabeth, 'Edward VI and the Pope' was clearly intended as counsel and admonition at a moment of crisis.

Margaret Aston claims no more for her book than a hypothesis or 'a walk around the painting'; but it is much more. Her detailed analysis of the content and form of paintings, her eye for technical problems and the politics of place combine with a vast learning in English and continental theological and humanist works, dazzlingly enriching our understanding of them all. Often we want to know more: how could the classical heritage be both the model for Protestant humanists and yet represent the evils of the Roman Church? Why did Eng- land lack an indigenous tradition of visual propaganda, and why did Elizabeth seem averse to its development? But far beyond the brilliant explication of one picture, Aston opens new insights into politics, reli- gion, and polemics in 16th-century England and Europe, and draws attention to the role of paintings, not as flattery of kings and queens but as counsel to (even criti- cism of) rulers. If historians are persuaded that in 1569 or 1570 a 'silent speaking pic- ture seemed a more tactful mode of deliv- ering an urgent message', they should be more inclined to study pictures and engrav- ings for evidence of both the mental furni- ture and the politics of the age.

The Personal Rule of Charles I, by Kevin Sharpe, was published by Yale, 1992.

Previous page

Previous page