MOTORWAY SADNESS

The M25 has led to yet greater pressure to build

on the Green Belt round London. Andrew Gimson reports

on the battle between hypermarkets and conservationists

'IT IS not an edifying spectacle to see groups of professional, intellectual and articulate people behaving at times as an unruly mob,' commented Mr Stanley Proc- ter, a planning officer in Surrey. He referred to the inquiry into the M25 inter- change at Leatherhead, which was so disrupted by local residents that it had for a time to be adjourned. The road, however, was afterwards built, and so were a bypass for Leatherhead itself, and several major intersections. Nowadays, ten lanes of traf- fic pass through the narrow strip of Green Belt separating Leatherhead from Ashtead.

The noise, a resident of Leatherhead informed me, can be heard throughout the town. `But you can't have progress and not give up something for it,' he added. 'If you're a traveller, it's got to be a good thing. We're 19 miles from Heathrow and Gatwick. And for going west or north it's great: M3, M4, M40, Ml, M11. Then we're well placed for the Channel Tunnel. . .

Nor is Surrey merely convenient. Much of it is extremely beautiful. 'The situation is unique,' Beatrix Potter's uncle wrote, in 1906, of a house, on the downs above West Horsley, where Beatrix herself often stayed. 'Only 26 miles from Hyde Park Corner, we are far from the madding crowd as if we lived at ten times that distance. I know of nothing near London like the miles of untouched natural wood- land which stretches on either side of our house.' Almost a fifth of Surrey is still wooded, the highest proportion of any county in England, and the woods do not, for the most part, consist of rows of conifers.

This combination of accessibility and beauty is extremely tempting to property developers. The pressure to `develop' is as great here as in any area served by the M25 road round London. Surrey exemplifies a problem which will become more and more acute for the Tories: that their commit- ment to the free market, and to private enterprise as the source from which wealth and jobs flow, cannot be reconciled with the commitment of their supporters, ex- cepting property developers, to the de- fence of the Green Belt. Just as the middle classes are determined as any Scargillite to defend restrictive practices from which they benefit at work, so they are implac- ably committed to defending the value of their houses, liable to be reduced by any local loss of 'amenity'. Liverpudlians may get on their bikes, but when they have pedalled south they find themselves ex- cluded from the economy by what they might recognise as a trade union mentality. Never mind the Liverpudlians, the be- haviour of the locals seems to say: we do not want land released for cheap housing, so that having found work, the northerners can also find somewhere to live. We want accommodation to remain impossibly ex- pensive for them. At most we would be prepared to see the Rent Acts abolished, but the Government has funked even that.

This is, of course, a provocatively tendentious way of putting it. 'Not in our back yard,' would be a fairer way to sum up the attitude of people in Surrey to development: they are frightened that horrible things are going to happen in their back yard. After all, a motorway has just been built through it. 'We've got to beat the speculators,' a retired man who had worked all his life in Surrey told me. 'You've got to be suspicious of anyone who owns land.' This man, I hasten to add, did not strike me as a crank, but as a thought- ful, level-headed type who had occupied a position of much responsibility. `A lot of agricultural land is likely to go out of use, and what is going to happen to that?' he demanded.

The temptations facing landowners are potentially immense, British Aerospace, which recently announced that it intends to stop making aircraft at Brooklands, near Weybiidge, is said to be hoping to sell 45 acres of the 132-acre site for a million pounds an acre. Part of the Sutton Park estate near Guildford, having been severed from the rest of the property by an 'improvement' to the A3, was sold to Sainsburys for, it is rumoured, six million pounds. They have built a superstore and car park on it. At a homelier level, a bungalow consisting mainly of breeze blocks and asbestos, on a not especially favoured site at East Horsley, a little way south of the M25, recently fetched £75,000.

Almost all of Surrey outside the towns has been designated as Green Belt. This does not, however, stop developers from hoping that they can find ways round planning restrictions. Otherwise much less land would have changed hands in recent years. It is impossible to prove that, for example, forestry companies which buy up land near the M25 hope one day to develop it, but only this hope can explain the prices they have paid, or the extent, in some cases, to which ownership of farms and woods has become fragmented.

If you should happen to own a wood in Surrey, and intend one day to build on it, the first step is to get rid of the trees, which the planners will want you to preserve. A local forester told me how this could be done. He had seen pigs and goats put in with trees, which may be relied on to destroy them. Or you could ring-bark them yourself, as happened to oaks at Byfleet, before a tree preservation order could be issued. At Brick Kiln Copse, near to the junction of the M25 and the A3, sold when a member of the Lovelace family died and 450 acres belonging to her were divided into seven different parts, major felling was soon found to be in progress. The new owner wanted to erect buildings for inten- sive agriculture, either battery hens or calf-rearing, which his opponents were sure would instead came to be used for warehousing. Rubbish was dumped into brick pits on the site, killing a protected Species, the greater crested newt. Once alerted, Guildford council intervened, but too late to save the newt.

A note of bathos often enters the pro- tests of conservationists: 'Local bank man- agers, whom I cannot name because of their customer confidentiality, are con- vinced that if nothing is done to halt this insidious process [the destruction of wood- land, and of rights of access] then by the year 2010, if not earlier, the North Downs Way will be wending its way through high-class executive housing estates.' Or again, from a lady who gave me much useful information: 'I can also give contact to gamekeepers who will tell of baby barn owls being burnt alive on Lord X's estate.' Or again, from a local historian objecting to a development undertaken by the gas board: 'If you feel you must go ahead with this act of vandalism in our parish, I suggest that you at least appear to be Public-spirited and that you finance a full-scale archaeological dig first.'

But if the visitor, by the ill-bred suspi- cion of a smile, suggests that they are becoming neurotic, the conservationists have only to say to him: 'Look at Wisley!' They wish him to examine the airfield, not the Royal Horticultural Society's gardens. 'If you want to make your name, blow the lid on Wisley,' I was told. Alas for my name, the Surrey Advertiser got there first. On 11 July it reported:

Residents at Elm Corner, Ockham, claim they are being peppered with sulphur and will soon suffer 'bombing raids' on Wisley Airfield, located behind their homes, which is being used for a variety of anti-social activities. Yellow powder deposits, claimed to have been identified as sulphur, are coming, residents believe, from oil drilling equipment dumped on the airfield and the 'bombing raids' with full sound effects will form part of filming work being done there. . . . They are convinced the gambit is to make life as unpleasant as possible now, in the hope that when a development plan for the airfield is unveiled later on, they will gladly accept it.

The full story of Wisley Airfield, too full to tell here, is indeed a scandal. The land on which its runway was built, long enough to take a VC10, was acquired by the Ministry of Defence in the last war, to test aircraft built at Brooklands, on the strict condition that it would be returned to agricultural use at the end of hostilities. It never was. After the Conservatives were returned in 1979, the Property Services Agency suddenly sold it, without taking up the runway, even though the Surrey Adver- tiser had found contractors who would pay for the privilege of doing so.

Last September, as a result of sustained local pressure, the pre-war footpaths which cross the runway were at last reopened. I walked these paths, which are unusual not only for running over concrete, but also because the local conservationists have had the ingenious idea of erecting motorway crash barriers along them. 'They don't look very nice but they stop aircraft landing,' it was explained to me. The owners, Wisley Properties, have responded by erecting a row of fake 1930s houses on the runway, for use in the John Boorman film Hope and Glory. The houses looked, I thought, astonishingly realistic, but rather out of place. Guildford borough council has just told Wisley Properties to take them down. The case continues.

Mr Humphrey Mackworth-Praed, of the Surrey Trust for Nature Conservation, seems reluctant to speak ill of any man, but confirmed the poor character of some landowners: 'It depends what they're in it for. If they're the old-fashioned type and take responsibility, they regard anything on their land as an asset: some rare species, they ask what they can do to help. But when you get people who're in it for the money you tend to get trouble. You get syndicate shoots who don't really under- stand. They come here to get their money's worth.'

These mercenary types often arrive by way of the M25. The road was built to benefit London, not Surrey. It was meant to act not as a magnet, attracting develop- ment to the Green Belt, but as a conduit which would keep long-distance traffic out of London. In this it has had a degree of success, though the price of success is such congestion that rather than queue to get through the Dartford Tunnel, or onto the M25 itself during the rush hour in Surrey, some traffic is already reverting to the old routes.

But the M25 has also proved highly magnetic. In vain the planners in Hertford- shire, for example, argued: 'Good roads should persuade developers to use land outside Hertfordshire which could be easi- ly reached through the M25.' Mr Geoffrey Smith, a partner in the planning consul- tants Nathaniel Litchfield, had told a con- ference before the motorway was fully open that he saw a generally accepted need for 12 to 15 free-standing superstores/ hypermarkets along its 121 miles, and another six to ten on the North Circular Road. Developers, employing the best possible experts to put their case, are now making intense efforts to persuade the Department of the Environment to let them meet this supposed need. 'Anyone who gets permission will have a licence to print money,' commented Mr David Gold- stein, of the firm Goldstein Leigh, which published the first report on the effect of the M25 on the property market.

If they are built, and several important inquiries into proposed sites are in progress at the moment, these superstores will probably prove popular, judged by the number of motorists they attract to conve- nient entrances just off the motorway. In that sense the road itself is popular: huge numbers of people use it. Yet this may indicate something short of enthusiastic endorsement. It is used, not loved. Even the AA has doubts: 'During commuting times the traditional good manners of driving seem to have disappeared. There is an atmosphere of aggression where no quarter is given and where motorists who try to drive safely are often bullied into higher speeds. The M25 section through Surrey is like a race track.'

It seemed so to me, and I regretted that my vehicle would not perform like a racing car. Plenty of people in Vauxhall Cavaliers were under the illusion that theirs do. The AA publishes a booklet about motorway driving, full of notes on etiquette such as 'Parking and reversing are taboo,' but except for saturating the motorway with police cars there is probably no way of making people drive better. Soon there will be another major accident, and for an hour or two the Cavaliers will slow down.

'All we can do is make the best of it,' the dispirited secretary of a local noise abate- ment society told me. Making the best of it presents the Government with a very tricky 'Mind you, it takes years of hard training.' problem. In the good old days almost everyone liked new roads. Lord Watkin- son, in the volume of memoirs which he has just published (Turning Points, Michael Russell Publishing, 49.95), recalls of his time as Minister of Transport in the late 1950s: At this time there was a national will for new roads and happy is the Minister who can identify with a surge forward in public opinion. The interest was all-pervading. I remember that during the customary visit that Ministers and their wives are invited to pay to Windsor Castle, I was alarmed to find how well briefed the Queen and the Royal Family were on road schemes, particularly those that linked Windsor with Buckingham Palace.

The minister visiting Windsor today is more likely, one guesses, to find himself talking about 'conservation issues'. When a minister wants to boast, he does not say he has been building motorways. As Secretary of State for the Environment, Mr Kenneth Baker instead declared, at a luncheon in Basingstoke on 7 March this year:

In this lovely part of England I had the opportunity in January to make a decision which I am glad to say was warmly welcomed by local people. I am of course referring to the decision I made . . . which effectively prevented an extra 1,900 new homes being built in north-east Hampshire.

Mr Ridley has succeeded Mr Baker as Secretary of State for the Environment, and he, it is thought, is more faithful to free-market principles, and less concerned to curry favour with voters. In private he might even argue that the market shows what people want, and that if they want superstores on green-field sites, they de- serve no better. But he is unlikely, in public, to abandon the Baker line, earlier enunciated by Mr Patrick Jenkin, that the Green Belt is safe with the Tories, at least until after the next general election. Too many of his colleagues, from constituencies where Telegraph readers have proved to be conservationists as well as Conservatives, are worried that the Tories will lose votes to the Alliance parties, if they do not show themselves sound on environmental ques- tions.

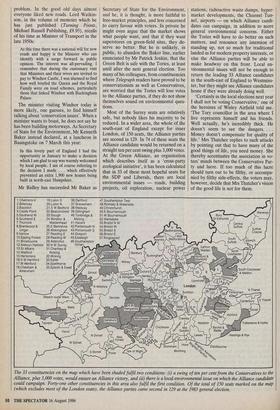

Most of the Surrey seats are relatively safe, but nobody likes his majority to be reduced. In a wider area, the whole of the south-east of England except for inner London, of 150 seats, the Alliance parties are second in 129. In 74 of these seats the Alliance candidate would be returned on a straight ten per cent swing plus 3,000 votes. At the Green Alliance, an organisation which describes itself as a 'cross-party ecological initiative', it has been calculated that in 33 of these most hopeful seats for the SDP and Liberals, there are local environmental issues - roads, building projects, oil exploration, nuclear power stations; radioactive waste dumps, hyper- market developments, the Channel Tun- nel, airports - on which Alliance 'candi- dates can campaign, in addition to more general environmental concerns. Either the Tories will have to do better on such matters, and renounce any intention of standing up, not so much for traditional landed as for modern property interests, or else the Alliance parties will be able to make headway on this front. Local en- vironmental issues will not be enough to return the leading 33 Alliance candidates in the south-east of England to Westmins- ter, but they might see Alliance candidates home if they were already doing well.

'Certainly in the local elections next year I shall not be voting Conservative,' one of the heroines of Wisley Airfield told me. 'The Tory councillor in the area where I live represents himself and his friends. Well actually, he's incredibly thick. He doesn't seem to see the dangers. . . . Money doesn't compensate for quality of life.' Mrs Thatcher replies to such attacks by pointing out that to have many of the good things of life, you need money. She thereby accentuates the association in vo- ters' minds between the Conservative Par- ty and lucre. If too much of this lucre should turn out to be filthy, or accompa- nied by filthy side-effects, the voters may, however, decide that Mrs Thatcher's vision of the good life is not for them.

The 33 constituencies on the map which have been shaded fulfil two conditions: (i) a swing of ten per cent from the Conservatives to the Alliance, plus 3,000 votes, would ensure an Alliance victory, and (ii) there is a local environmental issue on which the Alliance candidate could campaign. Forty-one other constituencies in this area also fulfil the first condition. Of the total of 150 seats marked on the map (which excludes most of the London seats), the Alliance parties came second in 129 at the 1983 general election.

Previous page

Previous page