THE REAL TROUBLE WITH CHRISTMAS

. . is that it is about salvation, and sin, as well as shopping,

says Christopher Howse `AND IS IT TRUE?' asked Betjeman in his poem suitably named 'Christmas'. That is the whole point. It is not the obvious horrors of late-night shopping in a crowd- ed Oxford Street that is the trouble with Christmas, it is something more fundamental.

The usual objections, such as high-street commercialisation, are too dreary to go into far, though they can be funny in their manifestations. One example is the adver- tisement which the Radio Times is running on Classic FM and suchlike channels: 'Christmas isn't Christmas without the Radio Times.' Now, if many people actually believed in what Christmas really is, they might be tempted to imitate Islamic extremists and put the Christian equivalent of a fatwa on the poor editor of the Radio Times.

The Radio Times, for God's sake! We are talking about Jesus Christ, very God made Man, the Saviour of all of us. What the hell (or heaven) are they talking about?

Christmas marks the birth of our Saviour. But there are in this country two common types of people: those who don't think they can be saved and those who think there is nothing to be saved from. Of the two, the second type is usually the more stupid. They often say that Christmas is for the kiddies — in other words that when they grow out of the lie of Father Christmas there's nothing else to believe in, and indeed that there need not be.

But if the Christians say we are to be saved, what do they think we are meant to be saved from? I suppose most people have little interest in theology, and this tempts them to presume that such ques- tions have never been gone into before. They have — and how.

Probably the most thoroughgoing exami- nation of the effect of the birth of Christ was undertaken by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century. Forget Einstein, Aquinas was probably the cleverest man who ever exist- ed. Few of us would even have dreamt up the sort of objections he presented to orthodox Christian views (and then he answered them). Some of them sound strange. Should Jesus have been born in the year he was born in? Was his flesh conceived first and then assumed by the Word (the Second Person of the Trinity)? Did Christ pay tithes in the person of his ancestor Abraham?

I am not quite sure what this last ques- tion is about, or at least why it matters. But it does show that not only did Thomas Aquinas take the matter seriously but he also scrutinised every angle he could. Most of the objections he considered came from questions posed by his contemporaries in university debate. Some have said his cen- tury was the age of faith. By all the evi- dence, it was the age of scepticism.

Jump forward six centuries and you find already an essential trivialisation, such as this kind of thing from Chambers' Book of Days:

The festival of Christmas is regarded as the greatest celebration throughout the ecclesi- astical year, and so important and joyous a solemnity is it deemed, that a special excep- tion is made in its favour, whereby, in the event of the anniversary falling on a Friday, that day of the week, under all other circum- stances a fast, is transformed to a festival.

That is of course complete drivel. The most important Christian feast is, and always has been, Easter, which marks the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. But the inter- esting thing about Chambers is that it stands in a mid-point between two popular understandings of Christmas. Its editor lived in the age of yule logs, boars' heads, the first Christmas cards and everything with which we have become familiar from Dickens's A Christmas Carol — and have mostly lost today. Yet Chambers can still refer to a Friday fast. Who keeps that now?

So let us jump back again to the 16th- century Protestant writer Richard Hooker. He is generally unread, because no one reads theology and because his prose is a bit difficult. But if you hold your breath you can enjoy his style in discussing Christmas:

Concerning the cause of which incomprehen- sible mystery, forasmuch as it seemeth a thing unconsonant that the world should honour but him that it honoureth as Creator of the world, and in the wisdom of God it hath not been thought convenient to admit any way of saving man but by man himself, though nothing should be spo- ken of the love and mercy of God towards man, which this way are become such a spectacle as neither men nor angels can behold without a kind of heavenly astonishment, we may hereby perceive there is cause sufficient why divine nature should assume human [nature], that so God might be in Christ reconciling himself the world.

Even if that seems to make little sense, it has to be admitted that the phrase 'a kind of heavenly astonish- ment', for example, is pretty good. Be that as it may, what are we supposed to be being saved from?

Again Aquinas gets round to it in the stately course of his Summa Theologiae. Would Jesus Christ (who is God), he starts by asking, have become man if we had not sinned? Probably not, he reckons.

There is a breathtaking line from the Exsultet, a hymn actually sung at Easter rather than Christmas, that goes: D felix culpa, quae talem ac tantum meruit habere Redemptorem' (0 happy sin which has deserved to have such and so mighty a Redeemer). This seldom fails to leave a wet eye in the house, for the reason that Christians are in general against sin and in principle fond of Christ. In that case, what is so happy or blessed about the sin of our first parents (Adam and Eve)?

Aquinas, taking his cue from Augustine, the African who died 800 years before he was born, says: 'Flesh blinded you, flesh heals you, for such is the coming of Christ that by flesh are the vices of flesh over- come.'

That sounds obscure, though quite poetic in Latin. (They were as fond of word-play and puns in the Middle Ages as people were in the 19th century — for instance, they said that the sin of Eve [Eva] was reversed by the greeting Ave of the angel Gabriel to the mother of Jesus.) Anyway, the 'flesh' reference would not have been obscure to the students who heard Aquinas lecture or Augustine preach. They would have known that there are two types of sin, actual sin and original sin. Just as both kinds of sin were committed by flesh- ly human beings, so both were healed by God made flesh.

In our way of thought, both kinds of sin are readily observable. Original sin is that nasty tendency we find in ourselves to do things we afterwards regret having done; and actual sin is, for example, telling a lie or stealing or doing what the Wests did the sky's the limit.

Anyone who hasn't noticed these phe- nomena needs his head examined. So what has Christmas got to do with it? 'Christ without any doubt came into the world to take away, not only that sin passed on to posterity, but also all the sins added subse- quently,' says old Thomas. He was talking about original sin and actual sin — that is, our nasty tendencies and our guilty acts. That sounds a comfortable doctrine. But `this does mean, however, that not all of the sins are in fact wiped away — some people fail to hold fast to Christ, as [the Gospel-writer] John notes, "The light came into the world and men loved the darkness rather than the light" ' That way hell lies.

In those comments, too, anyone who knows anything must recognise an echo. Even in the Radio Times there are lists of news programmes that are guaranteed to show how people choose the darkness, by stabbing schoolmasters or being horrible to hostages. Of course it would be nice if everyone were nice to everyone. But they are not. And this is the real trouble with Christ- mas. It is an annual festival when people are supposed to be nice. Scrooge is sud- denly converted. We find in fact that most people aren't, though. There is nothing wrong with trying to be nice, even once a year. It might be a useful reminder of a general obligation. But that kind of reminder only works in a social framework of convention and family con- nection. Our way of living is more usually individualistic and isolated. In Britain a common complaint (and I have asked a lot of people about it recently) is that families are the curse of Christmas. The kiddies might be all right, if you have them, but those in-laws, aunts and exes are a bloody nuisance.

At the moment there is a schmaltzy record in the charts called 'I believe'. It includes the song that goes: I believe for every drop of rain that falls

A flower grows.

You'd have to be daft to believe anything of the sort. Yes, yes, of course it is poetry, though bad poetry. It is the poetry of Christmas trees, crackers, turkeys, mince- pies and the Queen's broadcast. None of those is going to save us. And if we aren't saved we're all damned.

We might be, but I don't believe so. Let's go back to Betjeman:

And is it true? For if it is, No loving fingers tying strings Around those tissued fripperies, The sweet and silly Christmas things, Bath salts and inexpensive scent And hideous tie so kindly meant, No love that in a family dwells, No carolling in frosty air, Nor all the steeple-shaking bells, Can with this single Truth compare - That God was Man in Palestine And lives to-day in Bread and Wine.

Christopher Howse works for the Sunday Telegraph.

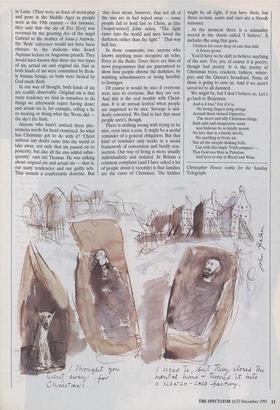

Previous page

Previous page