Dropmore Press Makes Good

The Holkham Bible Picture Book. (The Dropmore Press. £12 12s.)

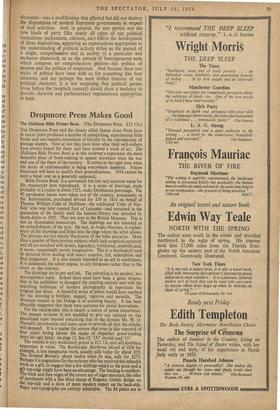

THE Dropmore Press and the closely allied Queen Anne Press have in recent years produced a number of enterprising, experimental little books and one massive monument of frivolity in the reproduction of postage stamps. Now at last they have done what their well-wishers have always hoped for them and have created a work of art. The Holkham Bible Picture Book is in this reviewer's experience the most beautiful piece of book-making to appear anywhere since the war and one of the finest of the century. It comes at the right time when the decay of craftsmanship is being everywhere deplored. Future historians will have to qualify their generalisations. 1954 cannot be such a bleak year as is generally supposed.

'Bible Picture Book' is a convenient but not very accurate name for the manuscript here reproduced. It is a series of drawings, made probably in London in about 1325, under Dominican patronage. The 42 parchment leaves were taken out of the country, presumably at the Reformation, purchased abroad for £30 in 1816 on behalf of Thomas William Coke of Holkham—the celebrated 'Coke of Nor- folk' who was later created Earl of Leicester—and remained in the possession of the family until the famous library was denuded by death duties in 1952. They are now in the British Museum. This is not an illuminated manuscript. The drawings are not intended as an embellishment of the tsxt; the text, in Anglo-Norman, is explan- atory of the drawings and fitted into the page where the artist allows. The pictures are not merely illustrative of the bible narrative. More than a quarter of them portray subjects which lack scriptural authority and all are enriched with details, legendary, traditional, symbolic and, it seems, occasionally purely imaginative. This is a theological tract in pictorial form dealing with man's creation, fall, redemption and final judgement. It is also plainly intended as an aid to meditation. It is addressed, the editor argues, to city burgesses rather than to the court or the convent.

The drawings are in pen and ink. The colouring is by another, less accomplished hand. Indeed there must have been a great tempta- tion to the publishers to disregard the painting entirely and with the searching technique of modern photography to reproduce the original line alone. A beautiful series of plates would have resulted for the drawing is brilliant, elegant, vigorous and versatile. The drowned woman in the Deluge is of arresting beauty. It has been plausibly suggested that these were cartoons for mural decorations.

For the mediaevalist this is clearly a source of prime importance. The present reviewer is not qualified to give any opinion on this specialised topic beyond remarking that to the layman Mr. W. 0. Hassall's introduction and notes seem to provide all that the scholar Will demand. It is a matter for sorrow that even in this vineyard of four years' loving labour the snake of imperfect proof-reading rears his ugly head; on page 12, line 19, '15v' should read 15.' collotype, eight in colour, the remainder in monochrome. The charac- ter of the original is particularly apt for facsimile.' There is no gilding, always the snag in reproduction. The paint, though more opaque than one could wish, has not the solidity of most medieval manuscripts. This solidity, so brilliantly and arduously counterfeited early in the lad' century by the hand-colouring of Henry Shaw and the lithography of Owen Jones, was quite lost in the photographic, three colour process at the beginning of this century. The collotypes here displayed, the work of the Oxford University Press, are models of fidelity. One can distinguish the hairside from the inside in the grain of the parchment. Only the wide margins destroy the illusion lg. identity. • The planners of this noble volume are all too modest. Only the editor's name is given. One would have welcomed a list of 'credits' in the manner of the cinema. Credit is indeed due to everyone from the magnate who financed the undertaking to the journeyman in the workshop; more than credit; joyous gratitude that an object of such rare beauty should have taken shape among us.

EVELYN WAUGH

Previous page

Previous page