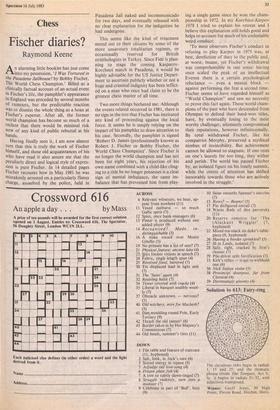

Chess

Fischer diaries?

Raymond Keene

An alarming little booklet has just come into my possession, 'I Was Tortured in the Pasadena Jail/louse! by Bobby Fischer, The World Chess Champion.' Billed as a clinically factual account of an actual event in Fischer's life, the pamphlet's appearance in England was preceded by several months of rumours, but the predictable reaction was to dismiss the whole thing as a hoax at Fischer's expense. After all, the former world champion has become so much of a recluse that there would be minimal risk now of any kind of public rebuttal at his hands.

Having finally seen it, 1 am now almost sure that this is truly the work of Fischer himself, and those old acquaintances of his Who have read it also assure me that the Peculiarly direct and logical style of expres- sion is pure Fischer. In 14 detailed pages Fischer recounts how in May 1981 he was mistakenly arrested on a particularly flimsy charge, assaulted by the police, held in

Pasadena Jail naked and incommunicado for two days, and eventually released with DO clear explanation for the indignities he had undergone.

This seems like the kind of treatment meted out to their citizens by some of the more unsavoury totalitarian regimes, or occasionally reserved for British ornithologists in Turkey. Since Fide is plan- ning to stage the coming Kasparov- Korchnoi match in Pasadena, it would be highly advisable for the US Justice Depart- ment to ascertain publicly whether or not a huge and criminal indignity has been inflict- ed on a man who once had claim to be the greatest chess master of all time.

Two more things bothered me. Although the events related occurred in 1981, there is no sign in the text that Fischer has instituted any kind of proceeding against the local force. It seems he is simply relying on the impact of his pamphlet to draw attention to his case. Secondly, the pamphlet is signed 'Robert D. James (professionally known as Robert J. Fischer or Bobby Fischer, the World Chess Champion)'. Since Fischer is no longer the world champion and has not been for eight years, his rejection of his own name combined with a child-like cling- ing to a title he no longer possesses is a clear sign of mental imbalance, the same im- balance that has prevented him from play- ing a single game since he won the cham- pionship in 1972. In my Korchnoi-Karpov 1978 I tried to explain his retreat and 1 believe this explanation still holds good and helps to account for much of his undeniably weird conduct:

'To most observers Fischer's conduct in refusing to play Karpov in 1975 was, at best, dereliction of duty to the public and, at worst, insane, yet Fischer's withdrawal was comprehensible in one sense: having once scaled the peak of an intellectual Everest there is a certain psychological reluctance — even a mental block —

against performing the feat a second time. Fischer seems td 'have regarded himself as "World Champion" and saw no necessity to prove this fact again. Those world cham- pions of the past who have descended from Olympus to defend their hard-won titles, have, by eventually losing to the most worthy challenger, ultimately compromised their reputations, however infinitesimally. By total withdrawal Fischer, like his compatriot Morphy, preserved a mythical nimbus of invincibility. But achievement cannot be allowed to stagnate. If one rests on one's laurels for too long, they wither and perish. The world has passed Fischer by, an isolated figure on his lonely summit, while the centre of attention has shifted inexorably towards those who are actively involved in the struggle.'

Previous page

Previous page