The beauty and beauties of England

Elizabeth Longford

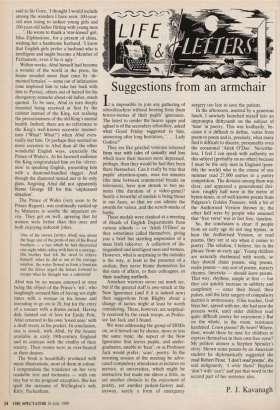

A PERSIAN AT THE COURT OF KING GEORGE, 1809-10: THE JOURNAL OF MIRZA ABUL HASSAN KHAN translated and edited by Margaret Morris Cloake with an introduction by Denis Wright Barrie & Jenkins, £14.95, pp. 317 If I were a publisher I might start a series of foreigners' diaries about Britain, for they possess an enviable recipe for success: they make us laugh today at what made people laugh at us yesterday. 'The Book of His Excellency the Persian Ambassador, 1819: an etching made by Richard Dighton during Abul Hassan's second mission to London Wonders' is how the Shah described this London Journal when its author returned to Persia, mission fulfilled.

It is the first but hitherto unpublished account of life in England as rendered by a Persian. Many 19th-century Europeans have gawped at Britain's strange ways, the latest being Prince Ptickler-Muskaw. But Abul's astonishment, as Sir Denis Wright points out, was at a different civilisation. Abul Hassan was born in 1776. His uncle was boiled in a vat of oil in 1801 by the same Fath Ali Shah who imprisoned, condemned to death and later reprieved Abul, sending him as envoy to England in 1809. The 33-year-old Abul's mission was political: to negotiate a Treaty of Friendship between Britain and Persia which would provide arms and money for the protection of India and Persia against Russia and Napoleon. Abul's extremely oleaginous references to the Shah in his diaries are intelligible in the light of that flaming vat. Let him fail or dawdle in his mission, and it is the boiling oil for him too.

Happily his lyrical style keeps politics at a distance. English fields and parks were `Gardens of Eden', noblemen were `cypress-tall', their ladies`jasmine- scented'. Hardly had he docked at Ply- mouth before the first 'wonders' began. A horde of harlots rushed on board. 'Why?' asked Abul. Because the captain would be faced with a labour shortage unless his crew were completely cleaned out of money.

Then those time-keepers:

Every man, whether of high or low estate, wears a watch in his waistcoat pocket; and everything he does — eating or drinking or keeping appointments — is regulated by time.

What a contrast to the timeless Orient! Abul was to bring many valuable clocks home to Persia.

Wonderful but less agreeable was the legal right of English servants to take their masters to court. Abul asked his official host, Sir Gore Ouseley, not to let his servants reveal this fact to Abul's servants. Compassion, however, was one of the things that Persians might well copy from the English. When Abul tumbled off his horse in the Park, all the other riders dashed up to offer help; in Persia people would simply say, 'What a shame — he's not hurt!'

The applause at Covent Garden astounded him: 'It could be heard by the Cherubim in heaven'. The Turkish ambas- sador had never been to the opera, so Abul told him: 'The nights are long in any country, but especially in London. From now on, I shall take you to the opera every night, and you will see strange and wonder- ful things.' But the custom of going to an `assembly' did not appeal. It seemed an unattractive mixture between a ladies' hammam and a gathering of souls at the Last Judgment.

Nevertheless, the ladies . . . At a party he met a lady missionary — 'famous for their goodness and beauty' — but like other English ladies she was scared by his huge black beard and fled. He preferred the bilingual Miss Metcalfe, daughter of an East India Company director, who could `laugh in Persian'. Actually he fell in love with one of the Foreign Secretary Lord Wellesley's nieces, probably Emily Wellesley-Pole, who was to marry the future Lord Raglan. Abul became much aggrieved when another of his hosts, Lord Radstock (Waldegrave), insisted on show- ing him old ladies and Old Masters when all Abul wanted was young mistresses. He said to Sir Gore, 'I thought I would include among the wonders I have seen: 100-year- old men trying to seduce young girls and 100-year-old ladies flirting with young men . . . He wrote to thank a 'star-kissed' girl, Miss Elphinstone, for a present of china, wishing her a handsome husband. 'I know that English girls prefer a husband who is intelligent and might become a Member of Parliament, even if he is ugly.'

Within weeks, Abul himself had become a wonder of the world in the press, his house invaded more than once by 'de- mented females' — some out of infatuation (one implored him to take her back with him to Persia), others out of hatred for his derogatory remarks about old ladies, much quoted. To be sure, Abul in turn deeply resented being received at first by the cabinet instead of the King, not realising the precariousness of the old King's mental health. Indeed, there are no references to the King's well-known eccentric manner- isms ('What? What?') when Abul even- tually met him. Or perhaps they seemed no more eccentric to Abul than all the other wonderful English ways, especially the Prince of Wales's. At his farewell audience the King congratulated him on his 'clever- ness' in speaking English, presenting him with a diamond-handled dagger. And though the diamond turned out to be only glass, forgiving Abul did not apparently blame George III for this 'unpleasant situation'.

The Prince of Wales (very soon to be Prince Regent), was continually rustled up by Ministers to soothe the impatient en- voy. They got on well, agreeing that fat women were better than thin ones and both enjoying indecent jokes.

One of his stories [writes Abul] was about the huge size of the penis of one of his Royal brothers — a fact which he had discovered one night while riding with him in a carriage. His brother had felt the need to relieve himself: when he did so out of the carriage window, the water flowed as from a fountain and the driver urged the horses forward to escape what he thought was a rainstorm!

Abul was by no means annoyed at once being the object of the Prince's 'wit', who laughingly accused him of having sex eight times with a woman in his house and intending to go on to 20, but for the entry of a rescuer with a drawn sword. Having duly fainted out of love for Emily Pole, Abul returned to his own 'loved ones' with a draft treaty in his pocket. In conclusion, one is struck, with Abul, by the beauty available in early 19th-century England and its contrast with the crudity of their society. Their rooms were as over-heated as their desires.

The book is beautifully produced with many illustrations, most of them in colour. I congratulate the translator on her very readable text and footnotes — with one tiny but to me poignant exception. She has spelt the surname of Wellington's wife Kitty, Packenham.

Previous page

Previous page