ARTS

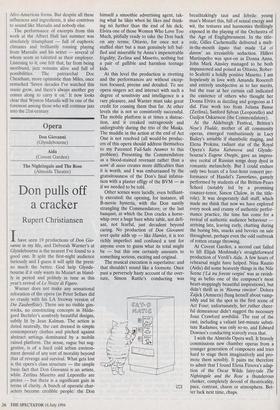

Sometime ago the late Miles Davis (born 1926) met the even more senior jazz trumpeter Adolphus `Doc' Cheatham (born 1905) on a transatlantic jet. They chatted amiably on the flight, then on arrival in France Miles was met by a phalanx of press. 'Mr Davis,' one journalist asked, 'is jazz dead?"Yeah', the great man replied, 'jazz is all dead — except Doc Cheatham.' Well, fortunately for us and for music Doc Cheatham is still with us, aged 89 (though Miles is not). Apparently immortal, Doc — who started out by accompanying Bessie Smith and carrying King Oliver's cornet case shortly after the first world war — has recently released an admirable record, and will be appearing at the Edinburgh Jazz Festival next month. But for the rest it must be admitted that Miles's judgment seems, in one's more pessimistic moments, quite plausible. Is this glorious music petering out, even though, to judge from the ever proliferat- ing festivals and CDs, its audience is not? Or is it perhaps destined to be mixed in ever more homeopathic doses into a melange of rock, rap, hip-hop, Afro, Scan- dinavian, Latin, Balkan, and folk rhythms, plus Tibetan prayer gongs, and anything else to be discovered in the encyclopaedia of world music? Already there are plenty of critics who talk as if this adulteration, or deconstruction, had already occurred, and they tend to refer to a ghostly entity 'which-we-are-calling-jazz', or worse, 'which-we-used-to-call-jazz'. Many of our best hopes of continuing to hear the undiluted, 120-proof stuff, rest on the career and example of a third trum- peter, Wynton Marsalis, who is appearing at the Royal and is now showing signs of maturing into the jeune premier. And it would have been hard to ask for a more presentable public face for the music than him — affable, good-looking, smartly suit- ed, a virtuoso performer of classical music as well as jazz, born in New Orleans, birth place of jazz, and playing that shining horn played by so many great Louisiana jazzmen from Buddy Bolden on — the trumpet. Marsalis — touted as the great new hope of jazz since he joined Art Blakey and his Jazz Messengers in his teens — is almost too perfect. And that is the criticism that has frequently been made of him. There is no doubt that Marsalis is an extraordinary musician from the technical point of view, but then there has always been more than fluency and expertise to jazz. Indeed, a number of great jazz musicians have been rather limited performers from the techni- cal point of view — Miles Davis is a good example, and so quite probably, although nobody knows, since he went mad,

Jazz

A blow for immortali

Martin Gayford on the survival of jazz after the death of the great players unrecorded, in 1907, was Buddy Bolden. Miles put this point himself, writing of Marsalis in his autobiography, `I knew he could play the hell out of classical music .. . but you need more than that to play great jazz. You need feelings and an understand- ing of life that et from living, from experience. I always thought he needed that.'

The relationship between Marsalis and Davis was a notoriously troubled one. Davis once threw him off stage in Vancou- ver, whereupon Wynton denounced Miles to the press for selling out through his espousal of jazz-rock fusion in the 1970s — setting off the process of dilution referred to above. Jazz-rock is indeed light-weight stuff, a great deal less interesting than either jazz or, for all I know, rock. It was a shame that Miles Davis spent so much time, and earned so much money, ($25,000 a night by the early Eighties), playing it. He set an unfortunate example. As an antidote, the acoustic purism of Marsalis — who once sacked his saxophon- ist brother Branford for playing with Sting — is to be welcomed.

But, on the other hand, there is also something worrying about Marsalis's earlier playing. It is accomplished, fluent, a little rythmically stiff, and a touch empty — rather like jazz played by a brilliant classi- cal performer, in fact. The life and urgency are absent. One of the mid-Eighties albums was entitled with unintentional aptness Hothouse Flowers — which said it all. The interesting thing is that Marsalis seemed to recognise this himself. Talking about his teenage days with Blakey he confessed, `I was just playing scales in whatever key my tune was in .. . that was enough to be con- sidered musical in my era'. On another occasion he pondered the difficult position of a musician who comes as late as he did in a tradition 'What I'm trying to do is come up to the standards all of these trum- pet giants have set' — Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, and Dizzy Gillespie among them — `And that's not an easy job.'

But — despite a degree of overnight success that would have turned anyone's head — Marsalis has set himself patient- ly to learning his craft. He has listened to venerable trumpeters like Clark Terry, Harry Edison, Joe Wilder and Doc him- self — rather as a classical musician might go and get tips from Brahms and Elgar if they were still around — and learned from them arcane lore about phrasing and mutes. As a result he has mastered the whole historic vocabulary of the trumpet, and is now playing much better than ever. He's not a performer of the emotional intensity of a Davis or a Charlie Parker — probably he lacks the demon-driven personality for that. But he is a different, less heart-on-sleeve sort of soloist — lyrical, and urbane with a beautiful big buttery sound.

Similarly, Marsalis has learned from jazz composers like Jelly Roll Morton, and — especially — Duke Ellington, and come up with an ensemble style that is both old and new. To date, the climax of this is his long piece 'In This House, On This Morning' (Columbia 474552, 2 CDs) — a tone poem that follows a southern Baptist service from the arrival of the congregation, to the cele- bratory meal afterwards. It constitutes a sort of double return to jazz basics — back to Ellington, unquestionably the greatest of jazz composers, and back to the gospel church, tap-root of jazz, blues and all other Afro-American forms. But despite all these influences and ingredients, it also contrives to sound like Marsalis and nobody else.

The performance of excerpts from this work at the Albert Hall last summer was absolutely triumphant — full of euphoric climaxes and brilliantly rousing playing from Marsalis and his sextet — several of whom seem as talented as their employer. Listening to it, one felt that, far from being moribund, jazz remains alive and full of possibilities. The patriarchal Doc Cheatham, more optimistic than Miles, once remarked 'Seven decades I've watched this music grow, and there's always another guy comes along to carry it on.' It now looks clear that Wynton Marsalis will be one of the foremost among those who will continue jazz into the 21st-century.

Previous page

Previous page