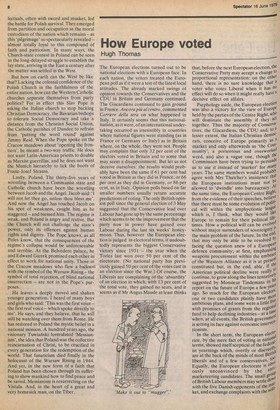

The Pope's new Europe

Neal Ascherson

Cracow Hanging dexterously to the cornice, so that he doesn't pitch out of the window, the Pope talks to the crowds singing and chanting in the night below. 'It's bad enough being that Pope in Rome. It would be far worse being Pope in Cracow, spending all the time standing at this window with no time to sleep and no time to think.' So the Avignon theory has to be discarded. In a Gothic collar, a rumpled group of Cracow intellectuals are drinking Armenian cognac out of tonic bottles: the tor council has forbidden the sale of spirits during the Pope's stay. The Avignon theory was that Pope John Paul II was going to move the Vatican to Cracow. Not only Would this satisfy his yearning to bring Slavic Catholicism back to the centre of the Church. Better still, say the intellectuals in a rench crusted by verdigris, it would provide against the advent of a Communist government in Italy. 'Inadmissible que le Pape reste . dans un pays communiste! . Croaks of laughter. You mount the steps, into the dazzling June afternoon. Today the Pope is going to the Mariacki church on the market square, by the mediaeval cloth hall. He is not setting out for two hours yet. But the route is lined five. deep already. There are yellow-andWhite Vatican flags, banners for 'Holy rather, Our Brother', homemade displays With the tough Wojtyla features done in fairy-lights. The road is already strewn with flowers. In the lane between the crowds, a four-year Old girl in the red-white-blue Krakowiak eostume is kneeling by herself on the street tidying the flowers into a neat row along the She brushes a ribbon off her face. The bells in the Mariacki spire, two hundred feet above her, strike five. A man in the spire begins to play a trumpet fanfare which breaks off in mid-phrase, when a Tartar arrow hit his predecessor in the throat. A faint nish of sound is carried across from the distant palace of the bishops. `Jedzi, jedzi — he's started'. After a week of the Papal pilgrimage through 'Polonia semper fidelis', one's sense of reality shrivels. It no longer seems odd that this second city of a Communist state should be drowned in Christian bunting, or that the population should be living night and day with the Pope — 'our Pope' — or that processions of kids are tramping through the whole inner city with guitars singing about Mary. The police wait in Columns of trucks, as the CRS do when Pans is tense. But their truncheons and pistols have been taken away. Outside the yawning brick gate of Auschwitz-Birkenau, a special 'CocktailBar' had been set up for the press. A million Polish Catholics were tramping merrily in, buying ice-creams, commemorative postmarks, tins of pilchard and Auschwitz keyrings, Down in the `Stammlager', by the wall where twenty thousand people had their brains blown out, photographers were hitting each other's pudgy faces with porky fists. Going to be like that, is it? But it wasn't.

Inside Birkenau, the dais was set square astride the railway line, on the ramp where the 'selections' were made. One of the great speeches of our time began, in this man's classical, sonorous Polish. It was an exorcism. It was a statement that Europe is here, in the ashes of four million people which still give the mud a dirty white hue, not in the paper-mountains of Brussels or the westerners' talking-house at Strasbourg. The people listened, sometimes wiping away tears, behind the wire of the gypsy camp, the mens' camp, the enclosure for Hungarian Jews. They were alive, with the special intensity of Polish living, a million men, women and children standing in the suffocating Silesian heat. At full production, with all five gas-chambers working as they did in the summer of 1944, it would have taken only three months to consume them.

He spoke about the Jews, who first learned the commandment 'Thou shalt not kill'. He spoke about the Russians, the nation and the soldiers who carried the main burden of a war for the freedom of the peoples. Afterwards a man who had been in Mauthausen said to me: 'Now it is really all over'. And a nun, taking communion before the Pope, whispered to him: 'I am a Polish nun. But I am also a Russian Jew'.

This was one of the moments when the Pope wept. And he wept at Nowy Targ, under the Tatra range, when a group of boys and girls began to sing the hymn 'God, King of the Mountains'. He recognised them: they were the 'Oasis' people, the members of a youth movement in his old diocese which dodges the authorities to carry out pastoral work in the hills. Inescapably, the word for all this is love. He receives it from the nation, as only liberators and dictators have taken it in history, but somehow he gives the dangerous gift back again, leaving on one side an intact man and on the other millions of individuals who go home with a better respect for themselves. They smile at him, talk to him, sing for him and clap. They never cheer.

It is harder to guess what can come of it all. The pilgrimage has distinct meanings for the Pope himself, for the whole strategy of the Catholic Church in the world, and for Poland. Pope Karol Wojtyla believes that God selected him — through the Cardinals — because he was a Pole. He has prayed and meditated to discover why Heaven required that a Slav from beyond the Elbe should rule the Church at this moment in history. Now he thinks that he knows. The features of Polish Catholicism are these: the mass classless base in the population; the claim to moral supremacy in society (which for this Pope means that the Church can support any government decently devoted to 'the cause of man', but should not be directly involved in support for a political party); the emphasis on the patriotic and independent nation; the defence of the free peasant on his strip of earth and of the unlimited family where father labours and mother mothers. These, accordingly, are the values which the Catholic Church in the world must now inherit.

But it won't be so easy to 'Polonise' the rest of the world In the first place, the West does not share the Pope's passion for a reunited Gross-Europa, a Christian continent in which the Slav and other eastern nations resume the prominence they had in the middle ages and the early modern centuries. Poland has always had this special enthusiasm for a European idea, the enthusiasm of the periphery. But the fat alliances of lands around Brussels have been separated from the East by forty years of Nazi occupation and Communism. Their commitment to a Christian Europe — as opposed to a 'Christian West', that sly old phrase of German propaganda — is mostly lip-service, an occasional impulse of charity for some remote 'church of silence'.

Secondly, history has sent Catholicism in the two halves of Europe on along quite different angles to the civil power. In the nineteenth century of the West, the violent struggles to draw a frontier of responsibility for society between the lay state and the Church produced modern republicanism — and middle classes which are often Catholic in observance but hotly anti-clerical in politics. The emerging industrial working-class gave its loyalty to Social Democracy or, later, to Communism: to an essentially atheist view of politics.

None of this took place in Poland. The nation spent that century in a desperate struggle, partitioned, to preserve its identity and regain independence. No laic movement, no 'croyant' but anti-clerical republicanism or modern liberalism emerged. Instead, the Church and the Catholic intel lectuals, often with sword and musket, led the battle for Polish survival. They emerged from partition and occupation as the moral custodians of the nation which remains — as this 'pilgrimage' so spectacularly revealed — almost totally loyal to this compound of faith and patriotism. In many ways, the Church-state contest in Poland can be seen as the long-delayed struggle to establish the lay state, arriving in the East a century after the matter was settled in the West.

But how on earth can the West be like that? Lacking the colossal confidence of the Polish Church in the faithfulness of the entire nation, how can the Western Catholic churches separate themselves from party politics? For in effect this Slav Pope is asking the Italian church to stop backing Christian Democracy, the Bavarian bishops to tolerate Social Democracy and take a distance from the Christian Social Union, the Catholic parishes of Dundee to refrain from 'putting the word round' against Jimmy Reid. When the Pope spoke on the Cracow meadows about 'opening the frontiers', he meant a two-way traffic. He does not want Latin-American priests to double as Marxist guerrillas, and he does not want the Munich hierarchy to lick the boots of Franz-Josef Strauss.

Lastly, Poland. The thirty-five years of wrestling between a Communist state and Catholic church have been the wrestling between Jacob and the Angel. Jacob said: 'I will not let thee go, unless thou bless me'. And now the Angel has touched Jacob on his spot of weakness, caught him as he staggered — and blessed him. The regime is weak, and Poland is angry and restive. But the Church will not challenge the state's power, only its offences against human rights and dignity. The Pope knows, as all Poles know, that the consequences of the regime's collapse would be unforeseeable and terrible. At the Belvedere palace, he and Edward Gierek promised each other in effect to work for national unity. Those in the Cracow meadows who flew a balloion with the symbol of the Warsaw Rising—the symbol of total rejection, of blind national insurrection — are not in the Pope's purposes.

He leaves a deeply moved and shaken younger generation. I heard of many boys and girls who said: 'This was the first voice — the first real voice — which spoke directly to me'. He says, and they believe, that he will still be watching over them from Rome. He has restored to Poland the mystic belief in a national mission. A hundred years ago, the visionary Tuwialiski formulated `Messianism', the idea that Poland was the collective reincarnation of Christ, to be crucified in every generation for the redemption of the world. That fanaticism died finally in the holocaust of the Warsaw Rising in 1944. And yet, in the new form of a faith that Poland has been chosen through its suffering to show mankind how to find peace and be saved, Messianism is resurrecting on the Vistula. And, in the heart of a great and very homesick man, on the Tiber.

Previous page

Previous page