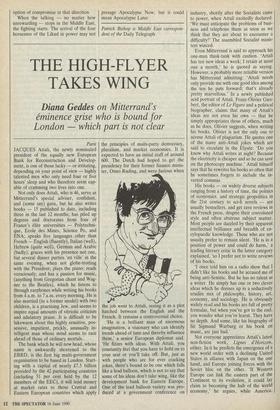

APOCALYPSE LATER

Patrick Bishop fears that

the new government of Israel could have disastrous consequences

Jerusalem IT SOUNDED like the arrival of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse rather than the formation of a new administration. 'A government born in sin,' thundered Shi- mon Peres. 'A government of national disaster,' predicted the Labour Party. The left-wing Citizens' Rights Movement prophesied that Mr Shamir and his part- ners could lead the country into 'a terrible new war'.

That was not how they saw things down at Liberty Bell Park, a pleasant space in West Jerusalem where the -old go to shmooze and the young to play.

`Thanks be to God for Yitzhak Shamir,' said Avraham, a spry 70-year-old with a toothbrush moustache. 'Perhaps now we will have peace in the land.'

Peace. Well yes, but of what kind? For the likes of Avraham and other supporters of the Likud and the far Right, peace means 'peace and quiet' in the occupied territories, and this is what Shamir has promised to deliver.

The new government which came into being on Monday night after six hours of acrimonious debate in the Knesset has been billed as the most conservative in the country's history. The new cabinet is cram- med with hard-liners with David Levy, Yitzhak Modai and Ariel Sharon, whose opposition stymied the Baker plan for talks between Israelis and Palestinians, all get- ting top jobs. To survive, Shamir has to rely on a clutch of ultra-right and ultra- orthodox mini-parties including the zealots of Tehiya and Tsomet who advocate annexation of the territories and mass Jewish settlement.

The wails of foreboding from the Left about the direction in which Israel is going are genuine enough but do not drown the fact that the new government is in step with public opinion in Israel.

When the Palestinian intifada broke like a lanced abscess in December 1988 bring- ing to an end 21 years of local and international complacency about the future of the West Bank and Baza Strip, events might have gone two ways.

The uprising could create a climate inside and outside the country for an equitable end to the whole depressing story. Alternatively a growing belief in the impossibility of peaceful co-existence with the Palestinians could pave the way for harsh solutions regardless of the furore this might raise in the rest of the world. The story told by the opinion polls is of a drift to the political margins, especially the right, and an increased willingness to con- template radical proposals.

In this respect the new coalition is representative. Among Mr Shamir's sup- porters (though outside his government) is Mr Rahamin 'Gandhi' Ze'vi, a former general with a disconcertingly icy gaze who was famous from his army days for keeping pet lions and patrolling the streets of Kiryat Shmona at night with a machine gun. His Moledet party advocates the annexation of the West Bank and the `transfer' (ie expulsion) of its Arab inhabi- tants.

This proposal finds favour with no less than 20 per cent of Israelis, according to a recent survey. Despite the daily death toll and the routine brutality shown towards the Palestinians, many — perhaps most Israelis are convinced that the army's handling of the intifada is not tough enough and that the Palestinians' aspira- tion to have their own country is a sense- less dream.

Some on the Right feel that it would be kinder to tell them so. 'At the moment we are throwing dust in their eyes,' said Yossi Chapinsky, a tenth-generation Israeli who used to vote Likud but thinks he will now support Moledet. 'We should tell them that we're not going to offer them peace talks or land. I know it's unfair but that's the way it is. We should say to them, "Look, nothing is going to happen." ' The new government's agenda is an alarming one — smash the intifada, plough on with settlements, slam into reverse on the peace process — but despite the doomladen forecasts of their opponents they are unlikely to rush to implement it.

The men at the top are mostly practical and practised politicians. The new defence minister, Moshe Arens, was rattled during his time at the foreign ministry by the depth of the Bush administration's distaste for Shamir and his policies. His likeliest course will be to make greater use of the extensive array of repressive measures at his disposal to wear the Palestinians down, rather than try any dramatic new tactics, as Ariel Sharon is constantly urging. David Levy, the new foreign minister, will also be inclined to tread carefully. He is a Moroccan-born Sephardi and in the past has shown himself to be less ideologically driven than his Ashkenazi partners. Unlike Shamir and Arens he backed the Camp David talks and was the only Likud minis- ter to vote in favour of pulling the army out of Lebanon.

Which brings us to Ariel Sharon. His return to the centre of political events after resigning from the government last year in protest at Mr Shamir's reluctantly received plan for elections in the occupied territories — has been the biggest cause of alarm among Palestinians and the Israeli Left. Ideally he would have liked to have returned to the defence ministry which he was forced to leave following the Kahan Report into the massacre of Palestinians by Christian militiamen in the Sabra and Shatilla camps in Beirut in 1982. As it is he has been appointed to the high-profile job of Housing Minister with special responsi- bility for supervising the absorption of Soviet Jews flooding into the country at the rate of more than 7,000 a month. In the newly created role of 'immigration Tsar' he has authority over the government's first priority.

It seems unlikely that Sharon will set out to provoke by immediately launching a programme of new settlements. It is diffi- cult enough filling the old ones. Nonethe- less there is plenty of scope for expanding existing settlements and strengthening the Jewish presence in the centre of large Arab towns like Nablus and Hebron.

The real push will be in East Jerusalem, occupied territory according to the world, but not to Israel. Unlike the dusty, sun- baked hilltops of the West Bank, Jeru- salem is somewhere the highly educated and largely unideological newcomers are prepared to live. According to unofficial counts some 10 per cent of them are already being channelled there (which puts in perspective the government claim that only half a per cent of Russian Jewish immigrants are settling in the territories.) Despite all the sound and fury of Shar- mir's rhetoric and his undoubted commit- ment to the notion of Eretz Israel, the prime minister detests action and is at his happiest stopping things happening. This tendency is all to the good when it is used against Ariel Sharon, who is as much hated by Shamir as he is by anyone in the Labour Party. It becomes dangerous, maybe catas- trophically so, when it is employed to delay, frustrate and finally cripple the latest American-inspired attempts to find an Israeli-Palestinian settlement. But the ideological constituents of the new govern- ment mean that Shamir does not have the option of compromise in that direction.

When the talking — no matter how unrewarding — stops in the Middle East, the fighting starts. The arrival of the four horsemen of the Likud in power may not presage Apocalypse Now, but it could mean Apocalypse Later.

Patrick Bishop is Middle East correspon- dent of the Daily Telegraph

Previous page

Previous page