See What I Mean ?

BY ROBERT HANCOCK TO use its own clichds, the development of the British popular dance tune record business since the war. `growthwise, profitwise and saleswise, has been sensa- tional. See what I mean?'

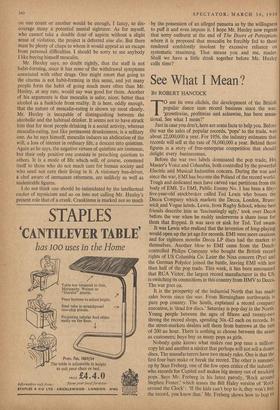

Just in case you don't, here are some facts to help you. Before the war the sales of popular records, 'pops' to the trade, was about 22,000,000 a year. For 1956, the industry estimates that records will sell at the rate of 58,000,000 a year. Behind these figures is a story of free-enterprise competition that should delight every businessman.

Before the war two labels dominated the pop trade, His. Master's Voice and Columbia, both controlled by the powerful Electric and Musical Industries concern. During the war and since the war, EMI has become the Poland of the record world. Tough and dedicated men have carved vast partitions from the body of EMI. To EMI, Public Enemy No. 1 has been a fifty- five-year-old stockbroker called Ted Lewis who bosses the Decca Company which markets the Decca, London, Bruns- wick and Vogue labels. Lewis, from Rugby School, whose best friends describe him as 'fascinatingly ugly,' took over Decca before the war when he rashly underwrote a share issue for them that flopped. It was save or sink for Ted. Ted swain.

It was Lewis who realised that the invention of long-playing would open up the jet age for records. EMI were more cautious and for eighteen months Decca LP discs had the market Ii' themselves. Another blow to EMI came from the Dutch- controlled Philips Company who bought the British record rights of US Columbia Co. Later the Nixa concern (Pye) and the German Polydor joined the battle, leaving EMI with less than half of the pop trade. This week, it has been announced that RCA Victor, the largest record manufacturer in the US. is switching its connections in this country from HMV to Decca. The war goes on.

It is the prosperity of the industrial North that has made sales boom since the war. From Birmingham northwards is pure pop country. The South, explained a record company executive, is 'dead for discs.' Saturday is pop day in the North. Young people between the ages of fifteen and twenty-two throng the record shops, spending 30s.-£2 each on records. In the street-markets dealers sell them from barrows at the rate of 200 an hour. There is nothing to choose between the sexes as customers; boys buy as many pops as girls.

Nobody quite knows what makes one pop tune a million- copy hit and another a stinker that perhaps will not sell a dozen discs. The manufacturers have two steady rules. One is that the first four bars make or break the record. The other is summed tip by Stan Freberg. one of the few open critics of the industry• who records for Capitol and makes big money out of mocking pops. Says Mr. Freberg in his latest parody, 'Rock around Stephen Foster,' which teases the Bill Haley version of `Rock around the Clock' : 'If the kids can't bop to it, they won't buy the record, you know that.' Mr. Freberg shows how to bop lo 'Jeannie with the Light Brown Wig.' Fortunately Mr. Foster, the author of 'Jeannie,' is dead.

The kids won't bop to it and they won't buy it unless they hear the record or hear and see someone play it on TV. So to plug pops a new and sometimes sinister character has come to Tin Pan Alley. He is known as the 'A & R' man—the Artists and Repertoire manager. Prewar he hardly existed. A record executive explained : 'When EMI had the grip on the business they didn't bother much about plugging. They had a few characters in old school ties around the joint who wore monocles.' Today monocles are out of fashion at EMI too.

The A & R man—there are about twelve in Britain—decides what artist shall record what song, who will provide the accompaniment, what songs shall be bought and the way in which they shall be sung. He is also responsible for arranging the maximum number of 'airings' on the BBC and ITV for his firm's product. Probably his most important duty is the dis- covery of new talent to record for his firm. Public fancy in pops is fickle and today's stars may be tomorrow's dead ducks.

It is common ground that the BBC is run by worthy men and women who put up with poor pay for the sake of their souls. This is also true of the Metropolitan Police. Sometimes allegations of corruption and favouritism are made against both bodies. Sometimes they are true. It is on the weaker members of the BBC who have any influence on the choice or presenta- tion of records on the BBC (and the same men in ITV) that the heavy guns of the A & R man's expense accounts are sighted. Top A & R men have expense accounts of around £4,000 a year. More, if the firm thinks it necessary.

Apart from the normal business entertaining of influential record-programme personnel, the A & R man will sometimes make cash payments to the weak, help them buy new cars, pay for their holidays, furnish their homes, or indulge their passions for antiques or any other domestic interest. An A & R man explained to me : 'Look, son, the gimmick is nothing ostenta- tious, see what I mean, like mink coats. They just make for harsh comment from people who know what the geezer earns. see what I mean?' Sometimes recipients of gifts write to A & R givers and ask them not to do it again. Commented one A & R man : 'They're usually so embarrassed about it, they forget to return the gift.'

Purity among A & R men is a bit off-white sometimes too. A favourite fiddle is to sign up a well-known star on the quiet and agree to see that he or she gets the best songs in return for a 25 per cent. share of the artist's earnings. These can be £10,000 a year once he is a success on discs. For then he can get a threepenny royalty on every record and be assured of fourteen weeks' work a year—at £300 a week—in the top variety halls. Previous stage ability is not required. By the time the artist has paid 5 per cent. of his gross earnings to a publicity man—usually a friend or relative of the A & R man— and up to 25 per cent. to his agent, another friend of the A & R man, his gross income is halved.

A good 'bent' A & R man prefers to discover his own talent and get hilt under contract, through a nominee, at a fixed wage, say £20 a week. He will then see that his discovery gets the right songs to build him up. It is, of course, expensive to groom an ex-fudge-stinger from Southport. Perhaps his nose will require plastic surgery, his voice will need polishing, his accent changing, his teeth fixing and his hair and hands glamorising.

One A & R man had so much talent under contract that he became too ambitious. His firm fired him when they discovered that his artists were getting fifty-eight plugs a month on the BBC, and theirs only two. Another addition to some A & R men's incomes is the 'rewrite percentage.' This comes from publishers or song writers who want their work recorded. For 10 per cent. of the song's royalties the A & R man will 'rewrite' the number to suit his needs. The rewriting usually consists of changing about two words.

I read this story over to an A & R friend. 'Look,' he said, 'I'm not arguing about this stuff, but don't use it, pal. Prestigewise it would be bad for the industry, see what I mean'?'

Previous page

Previous page