New York theatre

Broadway buys British

Matt Wolf

Think Broadway,' exhorts the large, boldly-lettered sign in front of New York's St James Theatre, but, in context, what does this mean? Such cogitation has been increasingly rare of late, as the erstwhile Great White Way publically airs its grie- vances. Declining audiences, rising ticket prices and excessive critical severity: these are just some of the phenomena insiders point to in order to account for the diminution of a once-significant theatrical street. Nowadays, a Broadway thought more likely than not leads to Britain. Some fine indigenous shows are, of course, around — Tina Howe's Coastal Disturb- ances, to cite one current example. Yet more and more, everything has a familiar ring, as Broadway and the West End become increasingly interchangeable. New York theatre, in some form, will no doubt survive, but will it be anything besides a mutant cousin to London's?

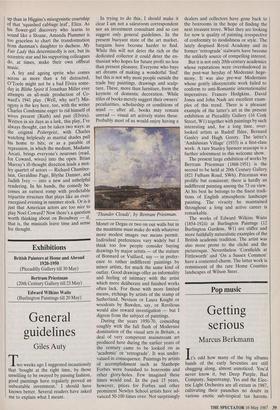

If audience approval alone is any guarantor, Britain's primary strength now lies in the musical, Broadway's once pre- eminent contribution in which London now dominates. Home-grown American musicals (Rags and Smile among them this season) open to mixed reviews and promptly close, insufficently pre-sold to surmount initial financial hurdles. By con- trast, Starlight Express opens to general vilification and proceeds to break box- office records at the cavernous Gershwin Theatre. Spectacle now rules the day and in that the British excel: Cats, Starlight and Les Miserables spin lucratively on, and Trevor Nunn, of all people, has become New York demiurge of the spectacular.

Les Miserables, in particular, makes an interesting case, since the social urgency and fervor of Victor Hugo's novel promises a musical that transcends spectacle. What chance, after all, for a show about faith if you cannot see the Godhead for the glitz? Unfortunately, its clouded vision is as apparent on Broadway as it was in Lon- don, where the stage at least looked amply populated compared to a New York coun- terpart that seems to have lost several bodies in the transatlantic crossing. (19th- century proles, I guess, are more expensive in New York.) Once upon a time, Trevor Nunn also directed the classics of Broadway, but his 1982 All's Well That Ends Well was a flop, so Shakespeare got the heave-ho. Noel Coward and George Bernard Shaw are the closest Broadway now gets to the world repertoire, and their track records might be less good if they weren't so damned English and elegant. (Neither Ibsen nor Strindberg has fielded a commercial New York production since 1982; small chance on Broadway of the Vanessa Redgrave Ghosts.) Currently, both Britons are on view: Coward in a starry American revival of Blithe Spirit (Neil Simon Theatre) directed by the expatriated Brian Murray; and Shaw in Val May's revival of Pygma- lion.(Plymouth Theatre).

Neither production hits the mark, though Pygmalion at least offers three British stalwarts in superb supporting per- formances: John Mills as the sooty social upstart Alfred Doolittle; Lionel Jefferies as a sonorous but gentle Pickering; and Joyce Redman as the canny Mrs Higgins, bent on defending Eliza from the dubious inquiry of her own phonetician son. For most observers, the real interest lies in the belated Broadway debut, at 54, of Peter O'Toole. Looking tall and pinched and faintly otherworldly, O'Toole arrives on the New York stage firm of voice and unsteady of foot, a mesmeric — if peculiar — presence who locates more drama in the tortuous act of sitting down and standing up than in Higgins's misogynistic courtship of that 'squashed cabbage leaf, Eliza. As his flower-girl discovery who learns to sound like a Sloane, Amanda Plummer is too graceless to chart the transformation from dustman's daughter to duchess. My Fair Lady this determinedly is not, but its eccentric star and his supporting colleagues do, at times, make their own offbeat music.

A fey and ageing sprite who comes across as more than a bit distracted, O'Toole might not be a bad Elvira some- day in Blithe Spirit if Jonathan Miller ever attempts an all-male production of Co- ward's 1941 play. (Well, why not?) Mis- ogyny is the key here, too, with the writer Charles Condomine eager to rid himself of wives present (Ruth) and past (Elvira). Written in six days as a lark, this play, I've always thought, can be taken two ways: as the original Poltergeist, with Charles watching helplessly as marital shades pull his home to bits; or as a parable of repression, in which the medium, Madame Arcati, brings everyone's neuroses (read, for Coward, wives) into the open. Brian Murray's ill-thought direction leads a mot- ley quartet of actors — Richard Chamber- lain, Geraldine Page, Blythe Danner, and Judith Ivey — into a new and unhelpful rendering. In his hands, the comedy be- comes an earnest romp with predictable tripartite structure that plays like an over- energised evening in summer stock. Or is it Just that American actors are too nice to play Noel Coward? Now there's a question worth thinking about on Broadway — if, that is, the musicals leave time and sense for thought.

Previous page

Previous page