It's the culture as well as the market

Robert Oakeshott

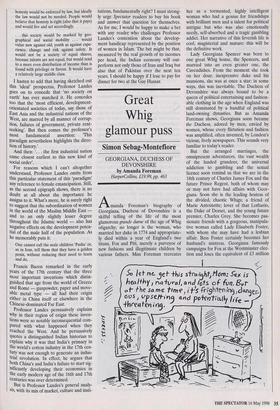

THE WEALTH AND POVERTY OF NATIONS by David Landes Little, Brown, £20, pp. 650

In countries like India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Nigeria and Ghana, I have always felt ener- vated by the slightest physical or mental exer- tion, whereas in the UK, France, Germany or the US I have always felt reinforced and stimulated by the temperate climate.

(Jayantanuja Bandyopadhyaya. Climate as an Obstacle to Development in the Tropics) Good government is not to be had for the asking. It took Europe centuries to get it, so why should Africa do so in mere decades, especially after the distortions of colonial- ism? And how about no government? At the moment, for example, Somalia is a political vacuum .. .

(David Landes p. 507) In general the best clue to a country's growth and development potential [emphasis added] is the status of women. This is the greatest handicap of Muslim Middle Eastern societies today, the flaw that most bars them from modernity.

Though it begins with some geography and ends with the question looking to the future — where are we going? — most of this wonderful book is history. More pre- cisely it is, of course, economic history, in the sense that it tells the story of the world's economic success and seeks to uncover what has underpinned and pro- pelled it.

Professor Landes is as much interested in the latter as in the phenomena or the numbers on the surface. His is not econom- ic history of the kind which calls for any algebraic expression. It is not even eco- nomic history which relies on endless tabu- lations of detailed statistics. There are fewer than ten tables in over 500 pages of text. On the other hand there are some rather notable maps. One depicts 'Ocean currents around the world'. Among these is one, north of Alaska, which goes round in a quite small circle. It is called the Beaufort Gyre (BG). I was not aware either of BG's existence or that the word gyre can be used to mean an ocean current. (For this review- er one of the real if less exalted charms of a book of this kind is when you stumble on something previously quite outside your

(David Landes p. 413)

knowledge and something which prompts the reaction, Well, fancy that! After the unforgettable Beaufort Gyre, my favourite example from Professor Landes's book is a people called the Guanches. They were found by the Spaniards in the 14th century inhabiting the Canary Islands and 'still liv- ing in the Stone Age'. Alas, none has sur- vived but their language was apparently linked to that of the Berbers, possibly with traces of Phoenician.) In his opening (geographical) chapter, entitled 'Nature's Inequalities', Professor Landes cites, as well as the first epigraph, a most telling observation by Paul Streeten:

Perhaps the most striking fact is that most underdeveloped countries lie in the tropical and semi-tropical zones, between the Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn. Recent writers (about economic development) have too easily glossed over this fact and consid- ered it largely fortuitous.

Given the effects of this particular exam- ple of Nature's Inequalities', I had rather expected Professor Landes to see it as an alibi for black Africa's rather moderate economic performance over the long march of history since most of us stopped hunting and gathering. Perhaps in a sense he does, because he never poses the ques- tion in relation to Africa, as he carefully does in the case of India and Latin Ameri- ca as well as most obviously of China and Japan: why did not serious and continuing modernisation start there, rather than in Europe? Perhaps by this very omission he offers Africa if not an alibi, then at least what Oxbridge graduates will know as an aegrotat: viz the special degree awarded to people prevented from being examined because of illness. But whether that is what he implies or not, he feels entirely free, as the second epigraph shows, to criticise almost without qualification the post- colonial economic development record of black Africa.

This kind of history is, of course, inescapably comparative. We discover why Europe went into the lead — from at least the early 15th century, say, from Henry the Navigator onwards — by reviewing the non-developmental performance of other possible leaders. Even if it does not excite the most interest, it is Professor Landes's treatment of those 'negatives' which will almost certainly provoke the most wrath in the non-Western world.

But I want next to share what I think is Professor Landes's main message and illus- trate how he arrives at it by focusing on his treatment of the primacy both of Britain with its first industrial revolution and of the earlier development achievements of west- ern Europe's Middle Ages. The author invites his readers to think of those Middle Ages as characterised by an array of most valuable inventions and innovations, or anyway of their widespread geographical diffusion: the 'wheeled plow with deep cut- ting iron share', the water wheel and, quite unrecognised by me before reading this book, eyeglasses. But we are also reminded of windmills and, not least, perhaps indeed Professor Landes's favourite example, of the mechanical clock. The author concludes by inviting us to see Europe's Middle Ages as 'one of the most inventive societies that history had known' and not 'as a dark interlude between the grandeur of Rome and the brilliance of the Renaissance'.

And underneath all that innovation and inventiveness? Well, following Adam Smith, Professor Landes concludes by say- ing: 'In the last analysis I would stress the market.'

On the other hand he also invites us to recognise three key elements in the Judeo- Christian culture as having played their part:

The Judeo-Christian respect for manual labour.

The Judeo-Christian subordination of nature to man.

The Judeo-Christian sense of linear time.

I suspect that there may well be those who find the first and third of those cultur- al components as rather too Cromwellian for comfort. However, the point to stress is that Professor Landes adopts the same approach when he turns his attention to the world's first industrial revolution in Britain in the 18th century. There are, of course, its material antecedents: improved agriculture, improved transport and indeed improvements, technical and otherwise, in almost every aspect of the country's economic life. Having covered these in review, he continues with what are perhaps two of the most striking passages in this whole marvellous book:

The early technological superiority of Britain in these key branches was itself an achieve- ment — not God-given, not happenstance, but the result of work, ingenuity, imagination and enterprise.

And he goes on: The point is that Britain had the makings; but then Britain made itself. To understand this, consider not only material advantages (other countries were also favourably endowed for industry but took ages to follow the British initiative) but also the non-materi- al values (culture) and institutions [emphasis added].

What follows is a long list of the legal and political preconditions — including both 'secure rights of property' and 'secure rights of personal liberty' — which were present in 18th-century Britain and provid- ed the framework in which people like Newcomen, Hargreaves and Arkwright could make their pioneering and creative inventions. That list in turn is followed by a sketch of the main values which would need to be reflected in a society which sought to perform the best from the view- point of economic development and wealth creation:

This ideal society would be . . honest. Such honesty would be enforced by law, but ideally the law would not be needed. People would believe that honesty is right (also that it pays) and would live and act accordingly.

. . . this society would be marked by geo- graphical and social mobility . . . would value new against old, youth as against expe- rience, change and risk against safety. It would not be a society of equal shares, because talents are not equal, but would tend to a more even distribution of income than is found with privilege or favour. It would have a relatively large middle class.

I hasten to add that having sketched out this 'ideal' prospectus, Professor Landes goes on to concede that 'no society on earth' has ever matched it. He concedes too that the 'most efficient, development- orientated societies of today, say those of East Asia and the industrial nations of the West, are marred by all manner of corrup- tion, failures of government, private rent- seeking'. But then comes the professor's most fundamental assertion: 'This paradigm nevertheless highlights the direc- tion of history.' And then: `. . . the first industrial nation came closest earliest to this new kind of social order'.

For reasons which I can't altogether understand, Professor Landes omits from this particular statement of this 'paradigm' any reference to female emancipation. Still, as the second epigraph shows, there is no doubt at all about the importance he assigns to it. What's more, he is surely right to suggest that the subordination of women in the world of the Muslim Middle East and to an only slightly lesser degree throughout the Islamic world — also has negative effects on the development poten- tial of the male half of the population. As he memorably puts it:

One cannot call the male children 'Pasha' or, as in Iran, tell them that they have a golden penis, without reducing their need to learn and do.

Francis Bacon remarked in the early years of the 17th century that the three most important inventions which distin- guished that age from the world of Greece and Rome — gunpowder, paper and move- able metal type — all had their origin either in China itself or elsewhere in the Chinese-dominated Far East.

Professor Landes persuasively explains why in their region of origin these inven- tions were so notably inconsequential com- pared with what happened when they reached the West. And he persuasively quotes a distinguished Indian historian to explain why it was that India's primacy in the world's cotton industry in the 17th cen- tury was not enough to generate an indus- trial revolution. In effect, he argues that both China's and India's failure to start sig- nificantly developing their economies in the early modern age of the 16th and 17th centuries was over determined.

But is Professor Landes's general analy- sis, with its mix of market, culture and insti- tutions, fundamentally right? I must strong- ly urge Spectator readers to buy his book and answer that question for themselves. As for me, I would be happy to make a bet with any reader who challenges Professor Landes's contention about the develop- ment handicap represented by the position of women in Islam. The bet might be that, measured by the real growth of its incomes per head, the Indian economy will out- perform not only those of Iran and Iraq but also that of Pakistan over the next ten years. I should be happy if I lose to pay for dinner for two at the Gay Hussar.

Previous page

Previous page