Fingers Crossed in Helsinki

By RICHARD BAILEY

Tarc no direct flights from Helsinki to Brussels, and the majority of Finns appear

to see no reason for changing this situation at present. This does not mean that the Finns have not been following the Common Market negotia- tions very closely. But it is a characteristic of buffer States that they must contrive to look in both directions at once, and 800 miles of com- mon frontier with the Soviet Union serve to con- centrate the attention of Finnish politicians most wonderfully.

Two clear impressions emerge from a visit to Finland. First, that neutrality is a mobile and flexible condition with as many permutations and combinations as membership of the Com- monwealth. The other is that sA hilc the Finns clearly take more pleasure in looking West rather than East, they are understandably not prepared to do more than adopt a wait-and-see attitude to Britain's attempt to enter the Common Market.

Earlier last year the Finns were adopting a similar attitude 10 their own application for association with the EFTA. In the event they were able to associate, by persuading the Russians that EFTA had no political Overtones. Neutrality for Finland means much more than not joining this or that group. For example, the Finns were forced to, give house-room to the Youth Festival held at Helsinki at the beginning of August as a proof that they were not pro- Western. As things worked out the Festival proved that Finland was not pro-Eastern either, a demonstration that considerably embarrassed the Government and led President Kekkonen to make a special personal appearance at the Festival. The favourite Finnish syllogism for 'neutrality' is non-involvement. This implies not so much minding your own business as going out of our way to keep out of trouble. The sudden withdrawal of the main opposition candidate in the presidential elections this spring

after Mr. Kekkonen's sudden summons to Moscow, has been the most spectacular illustra- tion of this principle to date.

What would non-involvement mean if it came to negotiations for Finnish association with an expanded European Economic Community? The short answer is that the Finns have got to go slow ahead while concentrating on what is happening astern. They will be confronted with a very difficult economic situation if Sweden secures some form of association with EEC that gives its pulp, paper and sawn wood products a tariff advantage in the EEC. It was a similar position in relation to the British market that led the Finns to make an all-out effort to become associate members of EFTA. Looking eastwards the Finns are confronted by two hard economic facts. The first is that the USSR will certainly claim most-favoured-nation treatment for its products in Finland. The second is that an uncomfortably high proportion of Finland's engineering and shipbuilding industry is working for the Soviet market. A wholesale cancellation of orders for ships, as was done by the Soviets in 1958, could throw anything from 5,000 to 15,000 men out of work. The shipyards are particularly vulnerable with the majority of the items in their order books marked down for different iron-curtain destinations. But manY people doubt if the Russians would play this card again.

When the EFTA-Finland agreement was made the Finns had far more trouble negotiating with the Russians, who were not a party to it, than they had with the Seven. A major concession made by the EFTA Governments was the grant- ing of permission for Finland to maintain quota restrictions on certain goods featuring in the bilateral trade agreement with the Soviet Unio°. la particular this affected oil, of which Finland receives about 90 per cent of its requirements from the USSR, but cotton. sugar and fertilisers art also involved. Apart from maintaining quotas for USSR exports, the Finns negotiated tariff reductions on the so-called EFTA goods, items on which the Seven would have enjoY:cd advantage over the USSR in the Finnish market.

Similar action on both commercial fronts will probably be undertaken if Finland decides that some form of association with the EEC is desirable. This decision will not be taken until it is quite clear whether Britain is going to be or out of the EEC. The main questions put to visiting Anglo-Saxons at this time all touch orl this point. In particular, the Finns want to know whether, if Mr. Heath is able to secure 3 suitable agreement, Mr. Macmillan will be able to get the Conservative Party to endorse it. British participation in the EEC is regarded by manY Finns as an absolute condition of their Govern- ment having any closer connection with the Six - In economic terms the position is seen as a matter of maintaining access to the principal markets for Finnish pulp and paper on the same terms as Sweden. Politically, association in any form

raises considerable snags. It will be far more difficult for Mr. Kekkonen to persuade the Soviet Union that association with the EEC involves no pblitical commitment than it was in the case of the EFTA agreement. Many Finns think that it Would be much better for them, and for their Swedish neighbours, if Norway was not a mem- ber of NATO. The fact that it is, is regarded as an example of over-enthusiasm and under- experience on the part of the US State Depart- ment. The optimists claim to believe that Fin- land will be treated generously by an expanded EEC. The pessimists point to Mr. Khrushchev's attacks on the Common Market as a very un- favourable portent for the future.

On the home front conditions are reasonably good. Employment is still high and order books are reasonably full. One cloud on the horizon is that the negotiations between the employers and trade unions due to start shortly promise new wage agreements at a higher level. But for the time being the Finns are busy quietly waiting and seeing. Mr. Kekkonen has recently been to Russia for a meeting with Mr. Khrushchev and the feeling is that there is not much point in making any forecasts until the results of his discussions have been pondered.

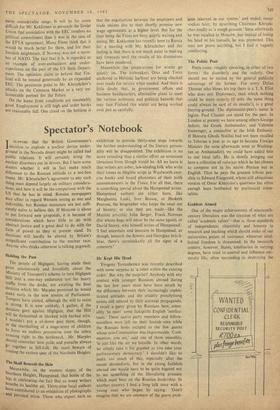

Meanwhile the preparations for winter go quietly on. The icebreakers Otso and Torso anchored in Helsinki harbour are being checked over ready for service when needed. And there is little doubt that, in government offices and business headquarters, alternative plans to meet the various economic and political hazards that may face Finland this w inter are being worked over just as carefully.

Previous page

Previous page