It's the rich wot gets the blame

Jonathan Clark

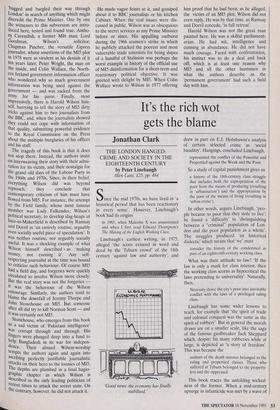

THE LONDON HANGED: CRIME AND SOCIETY IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY by Peter Linebaugh Allen Lane, £25, pp. 484 Since the mid 1970s, we have lived in 'a historical period that has been reactionary in every sense'. However, Linebaugh's book had its origins

in 1965, when Malcolm X was assassinated and when I first read Edward Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class.

Linebaugh's earliest writing, in 1975, alleged 'the scorn evinced in word and deed by the Tyburn crowd' of the 18th century 'against law and authority', and drew in part on E.J. Hobsbawm's analysis of certain selected crime as 'social banditry'. Hangings, concluded Linebaugh,

represented the conflict of the Powerful and Propertied against the Weak and the Poor.

So a study of capital punishment gives us

a history of the 18th-century class struggle that includes both the expropriation of the poor from the means of producing (resulting in 'urbanisation') and the appropriation by the poor of the means of living (resulting in 'urban crime").

In other words, argues Linebaugh, 'peo- ple became so poor that they stole to live': he found a 'difficulty' in `distinguishing between a "criminal" population of Lon- don and the poor population as a whole'. The struggles produced `an historical dialectic' which means that `we' must

consider the history of the condemned as part of an eighteenth-century working class.

What was their attitude to law? 'If the law is only a mask for class interest, then the working class scorns as hypocritical the laws pretending to universality'. Naturally, then,

Necessity drove the city's poor into inevitable conflict with the laws of a privileged ruling class.

Linebaugh has some wider lessons to teach, for example that 'the spirit of trade and colonial conquest was the same as the spirit of robbery'. But in general the morals drawn are on a smaller scale, like the saga of the famous gaolbreaker Jack Sheppard which, despite his many robberies while at large, is depicted as 'a story of freedom'. This was because the

authors of the death statutes belonged to the ruling and propertied classes. Those who suffered at Tyburn belonged to the property- less and the oppressed.

This book traces the unfolding wicked- ness of the former. When a mid-century upsurge in infanticide was met by a wave of hospital building, for example, this merely indicated 'a new organisation of reproduc- tion in the London labour market'. In the decades after c. 1760, men were coming to 'understand the materialism of historical dynamics'. This only made things worse. The industrial revolution did nothing to help the worker: 'the wealth was based upon inequality and riches meant poverty'; but this was just a new twist to the rule of a `thanatocracy' — 'the form of state power that had for two centuries maintained discipline in the capital by periodic mas- sacres at the gallows'.

The remarkable thing about these obiter dicta is that no single one of them is proved by the rich and fascinating evidence Linebaugh marshals in their support. This indeed seems to point the other way. Most robbery was for small sums: criminals robbed the poor rather than the rich, and the poor resented it. Crowds usually sanctioned public executions, demonstrat- ing only against specific ones, and it was highminded patrician reformers, not proletarian class warriors, who abolished the public spectacle of Tyburn in 1783.

Other evidence is not brought to bear. It might show, however, that although power and weakness, property and poverty, lived side by side in 18th-century London, class conflict (as distinct from the frictions and antagonisms which attend the human con- dition) did not emerge until the 19th. Social support and private charity, not theft, were the chief means of support of the indigent, and the populace could quite easily distinguish crime from honesty. Labourers did not scorn all laws, all of the time; they lastingly resisted some legisla- tion, like the Game Acts, which offended their keen sense of fairness. Only a minori- ty systematically embraced crime as a negation of the system as a whole; most were tempted into crime by ill fortune or chance opportunity, and, recognising this, the great majority of death sentences were commuted.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, England passed from an ancien regime where 'custom, license, usage, perquisite, "pillage and plunder" prevailed' to a care- fully quantified world in which input and output, costs and profits were measured, labour timed and regulated, and customary perquisites were often redefined as theft. On these distinctions, Marxist historians have built a whole theory of 'the repressions of gender, race, class and law'. It is, in its way, a peculiar achievement: Linebaugh has produced a perfect compendium of classic Marxist one-liners, redolent of the mood of 1975 when theories like this burst on the world in a volume entitled Albion's Fatal Tree. But Linebaugh is uniquely unfortunate: his long-meditated magnum opus, written in the vocabulary of the Brehznev era, is pub- lished after the failed Soviet coup. It is quite astonishing how different everything now looks.

Previous page

Previous page