ENGLISH, OUR ENGLISH

THE TROUBLE with viewers and listen- ers is that although they do not watch or listen with much care, they are absolutely certain that they have seen and heard cor- rectly. A week or so ago, a group known as Tin Machine appeared on Top of the Pops. Its drummer was a man called Hunt who, for some reason, had had his name tat- tooed on his knuckles. Twenty-nine pruri- ent prudes, mistaking the H for a C and assuming it was one of those words which Lord Rees-Mogg tells us are now used by Professors in private, rang in to complain about the BBC's use of bad language, campaign to subvert the morals of the young, left-wing bias, etc.

Britain is a country Where people apologise if someone else barges into them; they are far less forbearing towards the people who broad- cast to them. Bad lan- guage, whether misread on people's knuckles or Spoken. upsets some viewers greatly, though fewer now than in the past. Politics, by con- trast, seems to bother People less. Rank-and- file Conservatives were asked recently by their Party chairman to Com- Plain to the BBC if they believed it was dealing Unfairly with the Government, yet there have been far more calls Complaining about the recent post- ponement of Star Trek. The greatest passions are probably stirred up by the use of English on the 88C. Some people — judging by their let- ters to the BBC — are goaded beyond endurance by what they hear: can't stand it any longer! Over a period of years I have suffered under BBC mis- Pronunciation of this Gulf State [Qatar], Which has varied from "Catter", "Quater" (to rhyme with crater) and other hopeless variations, but you now appear to have set-

tled for "Catarrh".'

'Could you do something about financial experts who talk about "Wawn thay-ousand pay-ounds"? It grates so.' 'When will you stop employing idiots who cannot distinguish between "disinter- ested" and "uninterested"?'

'Can yon please do something to prevent the, demise of the sibilant "s" from the English language? In just the last week on BBC Radio 4 and BBC TV I have heard Dezember, dezolate, dizgrace, perzist, dezi- sion and Loz Angeles.'

Most of us have our King Charles's heads: 'REsearch' as opposed to `reSEARCH', perhaps, or misbegotten grammatical imports like the American subjunctive ('she asked that she not be identified'), or the home-produced anti-toff tendency which is killing off the gerund CI had no objection to him leaving'). Indeed, almost everything seems to be disliked by someone, even the standard English which the BBC is usually accused of abandoning: 'I propose your announcers etc. give us a widely used diet of words instead of what is often known as "affected speech" suitable to "clever" people in West London.'

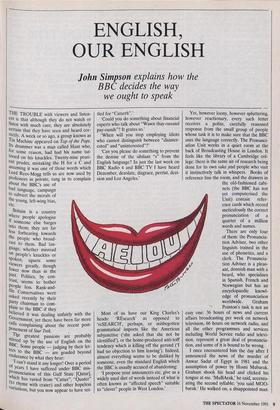

Yet, however loony, however spluttering, however reactionary, every such letter receives a polite, carefully reasoned response from the small group of people whose task it is to make sure that the BBC uses the language correctly. The Pronunci- ation Unit works in a quiet room at the back of Broadcasting House in London. It feels like the library of a Cambridge col- lege: there is the same air of research being done for its own sake and people who visit it instinctively talk in whispers. Books of reference line the room, and the drawers in the old-fashioned .cabi- nets (the BBC has not yet computerised the Unit) contain refer- ence cards which record meticulously the correct pronunciation of a quarter of a million words and names.

There are only four of them: the Pronuncia- tion Adviser, two other linguists trained in the use of phonetics, and a clerk. The Pronuncia- tion Adviser is a pleas- ant, donnish man with a beard, who specialises in Spanish, French and Norwegian but has an encyclopaedic knowl- edge of pronunciation worldwide. Graham Pointon's task is not an easy one: 36 hours of news and current affairs broadcasting per week on network television, 66 hours on network radio, and all the other programmes and services including World Service radio and televi- sion, represent a great deal of pronuncia- tion, and some of it is bound to be wrong.

I once encountered him the day after I announced the news of the murder of Anwar Sadat of Egypt in 1981 and the assumption of power by Hosni Mubarak. Graham shook his head and clicked his tongue at me. 'MuBArak,' he said, accentu- ating the second syllable; 'you said MOO- barak.' He walked on, a disappointed man. I long ago gave up trying to use travelman- ship as a counter to the Units edicts: claim- ing to have been to the place or to have met the person in question has no effect. The Pronunciation Adviser and his staff, like cricket umpires, are never wrong.

Yet they appreciate that rightness is something to. be re-examined at frequent intervals. And there is, of course, no single rule which applies. With some names the Unit accentuates the foreignness ('Gor- baCHEV', when every instinct makes one want to say `GORbachev). With others it favours the familiar; the Unit recommends 'Peking' rather than 'Beijing', has returned to 'Cambodia' from 'Kampuchea' and never left 'Burma'. Until a month or so ago, Maastricht was just 'a town in the least attractive part of the Netherlands, and the few people who mentioned it on the BBC tended to call it MAAstricht, because the first syllable usually catches the stress in British English. Now newsreaders and cor- respondents seem to be saying it all the time; and since the Dutch are a second-syl- lable people, accuracy demanded that the instruction should go out: MaaSTRICHT. Soon, no doubt, the place will slip back into pronunciation limbo and the unnatu- ral-sounding stress will lapse. Going native has its limits; the Unit prefers 'Felipe Gonthaleth', but that sounds too much like Violet Elizabeth Bott and the broadcasters rebelled. Ultra-authenticity has been out of fashion at the BBC since the days when Angel Rippon read the Nine O'Clock News, and would speak of `guerrEEyas', or pro- nounce 'Joshua Nkomo' Ndebele-fashion.

The legacy of Empire died slowly. The BBC was asked by the Kenyan government to change from the colonial `Keenya', so it did. It clung on to 'Sy-nee-eye' until the BBC correspondents in the Middle East pointed out that `Sinai' hadn't been pro- nounced like that since biblical days. The Pronunciation Unit does not like to move hastily: once a recommendation has been made those broadcasters who are on the BBC's staff are required to follow it. Great efforts are made to ensure accuracy. The prime minister of Grenada, Mr Nicholas Brathwaite, pronounces his name in vari- ous ways. After 14 lengthy calls to former ministers and leading. Caribbean journal- ists, the Unit settled on the home-grown version, 'Brathere.

In Britain, the Unit rings up every candi date in every parliamentary election to get the correct version of his or her name. BBC local radio stations compile lists of the worthies in their area, and these go back to the Unit as well, In the matter of place names, the Unit always checks two reliable contacts: the postmistress, say, or the local schoolmaster. It has learned to be wary of clergymen, because they usually come from outside. The Unit wants the local pronunciation of villages and some towns, though with others, and with cities, a standard version exists and `Newcasser or `1-lool' might sound mocking.

Yet even place names change. Outsiders move into a town or village and start pro- nouncing the name as it is spelt, rather than as the natives say it: `Skelmersdale' instead of `Skemmersdale', for instance. I asked about the choice of Daintree' or `Daventty'; the index-card, furry with age, said 'Recommended pronunciation: davventri; daintree accepted as used. Then it went on, 'From a contact at the home of the late Viscountess Daventry in Kensing- ton, 1515157. Our contact was horrified at the idea of the pronunciation deintri, which she maintained was 'modern', dating back only to the 1500s, whereas davventri went back to the Domesday Book.'

What enrages viewers and listeners most is the way they hear everyday English spo- ken. Regional accents have annoyed them since Wilfred Pickles was recruited to newsreading. When John Cole became Political Editor in 1981, his Northern Ire- land accent aroused a frenzy of Home Counties criticism: now he is one of the- best-regarded broadcasters in the country, a national figure who is genuinely liked and admired. Studies have shown that certain accents — West Country, Scots, Southern Irish — find general favour among viewers and listeners, while those of Birmingham, London, Liverpool and Belfast do not.

Some of the usages people criticise most fiercely derive from these unfavoured areas: `DISpute' instead of `disPUTE', for instance. Others come from the general haste which is an inevitable part of broad- casting: I often hear myself saying `seketry' for 'secretary'. It is ugly, but producing the necessary dexterity of tongue and jaw to give the first 'r' and the third syllable their proper force isn't always easy. Within the BBC a guerrilla ('guerrEEya) war is being fought out between those who think it sounds sharper and better to omit the defi- nite article before people's titles — 'Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir said today . . . — and those who feel that the time saved by such shorthand doesn't make up for the unreflective feeling it conveys. The habit comes from Fleet Street via commer- cial radio and is still spreading: though with luck it will never wholly conquer the BBC.

'FOR HEAVEN'S SAKE,' says a letter in the files, written in capitals to show extra anguish, 'INSTRUCT YOUR NEWS- CASTERS, WHO INFLUENCE SO MANY, TO USE CORRECT ENGLISH.' But correct English is like the BEF on the retreat towards the Channel: it never gets the chance to regroup and make a stand.

Since 1914 the pace of change in British English has been extraordinary, and it is unrealistic to expect that the BBC in gener- al, or the three linguists plus their clerk in the Pronunciation Unit, could possibly halt it, even if English were in the habit ...of accepting codification, which it isn't.

In the 1930s, John Reith set up the Broadcasting Advisory Committee, precise-

ly because listeners were continually com- plaining about the BBC's use of English. The Committee, like the Pronunciation Unit today, accepted that the language couldn't stand still, but its handbook, Broadcast English, recommended all sorts of usages which nowadays sound ludicrous: `balCOny' not `BALcony', 'cal-EYE-bre' not `CALibre', `HOSele' not 'hostile'. And yet in some sectors the front line remains surprisingly static; the Pronunciation Unit's files contain furious letters from the 1940s complaining about `conTROVersy' and our old friend liarASSmene as used in the case of Judge Clarence Thomas. The letters of complaint in 1981 were about precisely the same subjects as those in 1991: not a single new issue seemed to have emerged during the decade.

The greatest change, and the fastest, has come in terms of accent. I spoke recentlY to a university audience, and realised how different my accent and slang, the result of a 1950s childhood, seemed from theirs: all my `jolly goods' and `absolutelys', and all those vowels which are on their way to becoming museum pieces. Nor is this a new

process: recordings of Gladstone or Neville Chamberlain seem monstrosities of affecta- tion now, and the Queen herself had to tone down her English in the 1960s to something closer to that of her subjects. Where, then, arc we heading? My daugh- ters, cultivated young women reading,

respectively, Russian at Bristol and Classics

at Oxford, display an encroaching Ameri- canism which is no doubt the sound of the

future. In casual conversation they leave out some of the basic building-blocks of language: 'I said' becomes, 'I'm, like' — as in 'I'm, like, "What am I supposed to do now?'." On their lips, of course, I find it enchanting, but I shall not be so happy when it becomes general. If, in five years time, viewers and listeners write in to blame the BBC for it, they will be wrong: my daughters' generation hasn't picked it up from the BBC's own broadcasters, but from the great wave of American cultural and linguistic domination which started with talking pictures. Graham Pointon will have the difficult task of explaining this in his replies. And he will, perhaps, point cut that he is merely the BBC's adviser on such matters, and not its dictator.

John Simpson is Contributing Editor at The Spectator and Foreign Affairs Editor of the BBC.

Previous page

Previous page