Divided island in the sun

Richard West

Kyrenia In about 1956, a friend of mine who was trying to earn a living in journalism in Manchester, said he had just been offered a job on a newspaper in Cyprus, and did I think he should accept. Yes, of course, I said, for Nicosia sounded so much more fun than Manchester. He took the job, and on his second or third day was shot in the back and killed by an EOKA man, Nicos Samson, a very prolific murderer, who went on to lead the coup d'etat of 1974, and is now in prison; for ever, I hope. Partly because of that killing, and also because of the shrill hysteria over Enosis that made Greece inhospitable during the Fifties and eatly Sixties, I never enthused over the Greek Cypriot cause, as did, for instance the late Lord Bradwell (Tom Driberg). Nor for that matter did I accept the rival Turkish position, so I can claim impartiality, indeed a complete ignorance of the Cyprus issue; and therefore accepted this journal's offer to fly to the northern, Turkish-occupied zone at the expense of the self-styled Turkish Federated State of Cyprus.

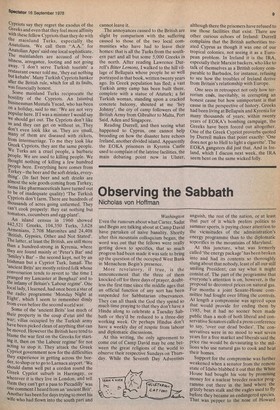

The offer to send a journalist came after the Turkish Cypriots took a three-page advertisement in the The Spectator, expressing their side of their case brought against them by Greeks who have lost their hotels in the northern part of the island. In particular the Greeks object to the continued use of the Dome Hotel in Kyrenia, which, so they claim, is wearing the carpets, rusting the taps and in general, bringing down the value. Although it is true that the plumbing gurgled a bit, the Dome seemed to be in good shape, and probably better maintained than the hundred hotels at Famagusta, now sealed off in one of the Turkish army's military zones, forbidden to foreigners, even to Turkish Cypriots. For anyone who detests the tourist industry, there is no more pleasant sight than this crescent of high-rise empty hotels, built so near to the beach that they used to blot out the afternoon sun. 'Cement concentration camps' they were described to me by a Turkish Cypriot who thinks the island is better off without the package tours from Birmingham and Bremen. However, even he was not too happy that tourists from Western Europe have now been replaced by visitors from mainland Turkey. Of these the most conspicuous are the 30,000 or so troops who have taken much land as militarY zones, including, besides the tourist quarter of Famagusta, a six mile beach near Kyrenia. Their military police, in shining helmets, white polo-neck shirts and matching gloves, parade up and down Kyrenia harbour, no doubt to the terror of any boisterous soldiers on leave, but rather to the disquiet of visitors. If you go for a walk and turn off from the main road, you soon find yourself stopped by a Turkish sentry guarding an artillery post or barracks. Indeed for a walking holiday, northern Cyprus is even more difficult than modern Rhodesia, or Vietnam during the war there. Some Cypriots still express gratitude to the mainland Turks. For instance a waiter at the Dome Hotel, told me before he took away my soup plate: 'We are better off now. There are 30,000 Turkish army, and have you ever seen such disciplined troops? They don't drink like the British troops did. In the Greek time (before 1974) when a Turk bought a bus ticket, they used to put aside his shilling to buy guns. When we bought an ice-cream they would ask why are you Turkish dogs buying ice-cream?' He even blamed the Greeks for leaving them with the Dome Hotel: 'They have brought all this on us. We don't want to run hotels. We would rather be happy even if it meant living under a tree'. In the 'Greek time' the Turks in Kyrenia were outnumbered four to one, as they were in the island generally; but this was the onlY Cypriot town in which the two communities were not entirely divided. Even so, a British resident recalls: The Greeks would send children into the Turkish quarter chanting 'Enosis'. It's amazing how many Turks have lost at least one of their family, or lost a limb or an eye. I get fed up at the pro-Greek slant of the British press and TV. I was living near here at the time of the coup and the Turkish invasion, and the Turks went out of their way not to attack villagers. The only screams we heard was during the coup when the EOKA people were roar' dering the Makarios supporters'. Although of course both Greeks and Turks accuse.d the other side of atrocities, it seems that in the Kyrenia area, especially at three villages on the Nicosia road, the Turks were the greater sufferers. In spite of past hatreds, many Turkish Cypriots say they regret the exodus of the Greeks and even that they feel more affinity With these fellow Cypriots than they do with the mainland Turks, especially the Anatolians. 'We call them "A.A." for Anatolian Apes' said one local sophisticate. Th. e mainlanders are accused of boorishness, arrogance, looting and not going away. 'I don't serve Turkish tourists' a restaurant owner told me, 'they eat nothing but kebabs'. Many Turkish Cypriots hanker after the British rule, which for all its faults, was financially honest. Some mainland Turks reciprocate the hostility of the Cypriots. An Istanbul businessman Mustafa Yucad, who has been on a holiday, said to me: 'We are not very Popular here. If I was a minister I would say we should get out. The Cypriots don't like US and they can get on without us. They don't even look like us. They are small, many of them are diseased with rickets, from intermarriage. To me they look like Greek Cypriots, they are the same people. We Turks are a cruel people, a barbaric People. We are used to killing people. We thought nothing of killing a few hundred People here. Everything here comes from Turkey the beer and the soft drinks, everything'. (In fact beer and soft drinks are almost the sole goods coming from Turkey; items like pharmaceuticals have turned out to be of inadequate quality) 'The Turkish Cypriots don't farm. There are hundreds of thousands of acres going unfarmed. They can't cook properly: they eat nothing but tomatoes, cucumbers and egg-plant'.

An island census in 1960 showed 442,521 Greeks, 104,350 Turks, 3,628 Armenians, 2.708 Maronites and 24,408 'British, Gypsies, Other and Not Stated'. The latter, at least the British, are still more than a hundred-strong in Kyrenia, where they are found mainly at 'Peter's Bar' and Smiley's Bar' the second kept, not by an Inshman but a Cypriot Turk, Ismail. The ancient Brits' are mostly retired folk whose conversation tends to revert to 'the time I Pranged my Lancaster at Benghazi' and to the infam y of Britain's 'Labour regime'. One local lady, I learned, had once been a star of the radio programme 'Monday Night at Eight', which I seem to remember dimly from even before the second world war.

Some of the 'ancient Brits' lost much of their property in the coup d'etat and the war; villas occupied by the Turkish army have been picked clean of anything that can be moved. However the British here tend to blame the war first on the Greeks for starting it, then on 'the Labour regime' for not acting to stop it. They attack the Greek Cypriot government now for the difficulties they experience in getting across the border, to shop or to go to Larnaca airport. 'We Should damn well put a cordon round the Greek Cypriot suburb in Harringay, or Wherever it is they live in London, and tell them they can't get a pass to Piccadilly' was one comment I heard from an 'ancient Brit'. Another has been for days trying to meet his Wife who had flown into the south part and cannot leave it.

The annoyances caused to the British are slight by comparison with the suffering caused to those of the two local communities who have had to leave their homes: that is all the Turks from the southern part and all but some 5,000 Greeks in the north. After reading Lawrence Durrell's Bitter Lemons, I walked to the hill village of Bellapaix whose people he so well portrayed in that book, written twenty years ago. Its Greek population has fled; a vast Turkish army camp has been built there, complete with a statue of Ataturk; a fat Turkish woman, standing upon a cracked concrete balcony, shouted at me 'hey Johnny', the cry of camp followers of the British Army from Gibralter to Malta, Port Said, Aden and Singapore.

Reading Durrell, and then seeing what happened to Cyprus, one cannot help brooding on how the disaster here echoes Ireland, another divided island. Apparently the EOKA prisoners in Kyrenia Castle used to complain of the latrine facilities, the main debating point now in Ulster, although there the prisoners have refused to use those facilities that exist. There are other curious echoes of Ireland: Durrell complains that the British authorities treated Cyprus as though it was one of our tropical colonies, not seeing it as a European problem. In Ireland it is the IRA, especially their Marxist backers, who like to talk of themselves as a British colony comparable to Barbados, for instance, refusing to see how the troubles of Ireland derive from Britain's relationship with Europe.

One sees in retrospect not only how terrorism ends, inevitably, in corrupting an honest cause but how unimportant is that cause in the perspective of history. Greeks had been living at Bellapaix and Kyrenia for many thousands of years; within twenty years of EOKA's bombing campaign, the Greeks have been forced out altogether. One of the Greek Cypriot proverbs quoted by Durrell makes that point exactly: 'One does not go to Hell to light a cigarette'. The EOKA gangsters did just that. And in Ireland, which I discuss next week, the IRA seem bent on the same wicked folly.

Previous page

Previous page