DRAWN BY THE SOUND OF GUNS

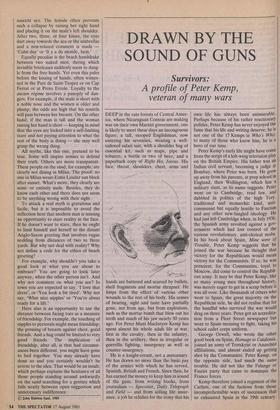

Survivors: A profile of Peter Kemp, veteran of many wars

DEEP in the rain forests of Central Amer- ica, where Nicaraguan Contras are making war on their own Marxist government, one is likely to meet these days an incongruous figure, a tall, stooped Englishman, now entering his seventies, wearing a well- tailored safari suit, with a shoulder bag of essential kit, such as maps, pipe and tobacco, a bottle or two of beer, and a paperback copy of Right Ho, Jeeves. His face, throat, shoulders, chest, arms and

hands are battered and scarred by bullets, shell fragments and mortar shrapnel. He limps from the effect of various other wounds to the rest of his body. His senses of hearing, sight and taste have partially gone, not from age, but from explosions, such as the mortar bomb that blew out his teeth and much of his jaw nearly 50 years ago. For Peter Mant Maclntyre Kemp has spent almost his whole adult life at war, first in the cavalry, then in the infantry, then in the artillery, then in irregular or guerrilla fighting, insurgency as well as counter-insurgency.

He is a knight-errant, not a mercenary. He has drawn no more than the basic pay of the armies with which he has served, Spanish, British and French. Since then, he has earned the money to keep him in sound of the guns, from writing books, from journalism — Spectator, Daily Telegraph and Field — and from selling life insur- ance, a job he relishes for the irony that his own life has always been uninsurable. Perhaps because of his rather reactionary politics, Peter Kemp has never enjoyed the fame that his life and writing deserve; he is not one of the 17 Kemps in Who's Who; to many of those who know him, he is a hero of our time.

Peter Kemp's early life might have come from the script of a left-wing television play on the British Empire. His father was an Indian civil servant, becoming a judge at Bombay, where Peter was born. He grew up away from his parents, at prep school in England, then Wellington, which has a military slant, as its name suggests. Peter went on to Cambridge, read law, and dabbled in politics of the high Tory, traditional and monarchic kind, anti- communist but equally hostile to Fascism and any other new-fangled ideology. He had just left Cambridge when, in July 1936, the Spanish army revolted against a gov- ernment which had lost control of the various revolutionary, anti-clerical mobs. In his book about Spain, Mine were of Trouble, Peter Kemp suggests that he joined the war because he thought that victory for the Republicans would mean victory for the Communists. If so, he was prescient, for the Communists, loyal to Moscow, did come to control the Republi- can army. It may be that Peter Kemp, like so many young men throughout history, was merely eager to get in a scrap before it was all over. Like thousands of others who went to Spain, the great majority on the Republican side, he did not realise that for, the handful who survived the war would drag on three years. Peter got an accredita- tion from a Fleet Street newspaper but went to Spain meaning to fight, taking his school cadet corps uniform.

George Orwell, who wrote the other good book on Spain, Homage to Catalonia, joined an army of Trotskyist or Anarchist affiliations, and almost ended up getting shot by the Communists. Peter Kemp, On the opposite side, had much the same trouble. He did not like the Falange or Fascist party that came to dominate the Franco forces.

Kemp therefore joined a regiment of the Carlists, one of the factions from those incomprehensible wars of succession that so exhausted Spain in the 19th century. The Carlists were led into battle by their ferocious priest. Having survived some months with the Carlists besieging Madrid, Peter Kemp became an officer in a still more fire-eating regiment, the Spanish Foreign Legion, whose motto was 'Long Live Death'. The punishment for trifling offences was to be whipped round the head with a bull's pizzle; all more serious crimes were punished by a firing squad. The French Foreign Legion sound like milksops besides these Spaniards and Portuguese, who thought nothing of settling down to sleep at night on a pile of corpses, shifting them round like pillows, for comfort. Even reading Mine were of Trouble Induces shell-shock. It seems incredible that anyone could have survived even a year of that war; and very few did. Near Teruel, in one of the bitterest fights, the Legion lost almost as many dead from cold as from the enemy. At one point Kemp visits the birthplace of Goya, who had depicted the horrors of war in Napoleon's time. Spain in the Thirties was just as ravaged by torture and death. Orwell, on his side, spoke lightly, almost approvingly, of the persecution of the Church. Peter Kemp, on his side, found villages where the Republicans had crucified the priest. He took pains to disprove some atrocity stories told against the Franco troops. He spent a grisly half-hour inspecting the Corpses of men killed by the Moors to show they had not been castrated. The Spanish Foreign Legion were merciful to Spanish Prisoners but shot all foreigners that they captured. Peter Kemp protested about this, and for his pains was ordered to execute a Northern Irish deserter from the International Brigade. It is one of the most painful episodes in a gruesome book. Kemp is still bitter against the Franco government because of the tens of thousands of people they shot after the war ended. 'It was very Spanish,' he adds, 'and the Communists would have killed even more.' In 1939 he met the English com- mandant of the International Brigade he had fought against on the Aragon front, lie said they'd have shot me if they'd caught me,' Kemp recalls.

Peter Kemp saw much more action in Spain than Orwell did. Unlike Orwell, he also enjoyed himself when he was not fighting. He went back to England once, he had jaunts to France and to his brother's ship in the Royal Navy; there were many boozy dinners and parties with fellow officers, visiting politicians and war corres- pondents, including Kim Philby. By the end of 1938, Kemp's luck had run out. He was wounded in quick succession in the chest, the throat and the shoulder. After a short sp,-.1 of sick leave in Jerez, drinking the local product, and Biarritz where he met Esmond Romilly, en route for the Republican side, Kemp returned to the front line. A grenade, 'it was only a small one, luckily', almost blew off his jaw. Lying conscious, in agonising pain, at a forward hospital, he heard one of his brother officers say that 'Peter will be dead in a few hours'. He managed to survive a series of hideous operations made worse by burns to the throat and long journeys bumping around in the back of a lorry. When he was well enough, the surgeons did an operation, without anaesthetic, to clear the shrapnel and pus out of his face and sew up his jaw. Kemp drank a whole bottle of brandy at intervals in the opera- tion. His account is good to read for people who fear the dentist.

Six weeks after getting demobilised from the Spanish Army, Peter Kemp was trying to join the British Army to fight in the war that had just broken out against Germany. He was at first turned down on the grounds of health, not, as some have said, because he had served in a foreign army. This ban applied only to those who had joined a foreign political party and even then was loosely applied. He eventually made his way into a special irregular unit that was to be SOE (Special Operations Executive). In April 1940, Kemp set off on a mission to Norway for his first experience of war on skis, but on the way his submarine was torpedoed by a German U-boat. After surviving this mishap under water, Kemp took to the air, learned to parachute, made several raids on France and was later dropped into enemy-occupied Albania. He and his friends there, like Julian Amery, managed not to get murdered by enemy Fascists and scarcely less venomous allies such as the Communist leader, Enver Hoxha. The Yugoslav Vane Ivanovie (now Consul-General of Monaco in London) recalls meeting Kemp at Bari and asking him what he thought of the Albanians. `What can one think of a nation,' came the reply, 'whose emblem is a two-faced buz- zard?' (Actually, a two-headed eagle.) In Leon, Nicaragua, this year, Richard West was having a drink with Kemp when: `Suddenly Peter let out a whoop of joy. He had seen on the back of a paper the news of Enver Hoxha's death. He got to his feet, lifted his mug of beer and exclaimed: "Stoke well . . . the furnaces of Hell" ' After Albania, and southern Yugosla- via, Kemp was dropped into Poland. He saw in the New Year of 1945 with a band of warriors of the Home Army, the non- Communist guerrillas, who celebrated with vodka and joyful fusillades into the night air, which of course alerted the Germans. At dawn he managed to escape, while his hosts held off an attack with a couple of Bren guns. When the Red Army overran their positions, Kemp and his colleagues were told by London to make themselves known to the Russian allies, who instantly arrested them. For a month he and his group were prisoners of the NKVD, who shot the Poles and would have shot Kemp but for interventions from London.

After recovering from the Russian pris- on, and a bibulous holiday in Ireland, Kemp flew to the East to fight the Japanese. He parachuted into Thailand, having just swallowed a flask of brandy to overcome the effects of dysentery and malaria, and proceeded on horseback into the forest near Laos. As soon as the Japanese surrendered, Kemp found him- self fighting side by side with the French against the Vietnamese Communists (then known as Vietminh and later as Vietcong) who had embarked on the massacre of the former colonialists. One French officer was shot dead, point-blank, at his side. He started running guns to the French and had his first taste of naval warfare, fighting machine-gun battles up and down the Mekong River. The Vietminh put a price on Kemp's head and managed to kidnap him; but he escaped. Not to be outdone, Kemp set out to kidnap or murder the. Vietminh chieftain. After six months of fighting in Laos, in which he had almost single-handedly opened the Vietnam War, Kemp was told to liberate Bali. His third book of memoirs, Arms for Oblivion, carries a breath-taking photograph of one of the semi-naked women he freed.

After ten years of fighting, Kemp mar- ried again (the first time was a failure), went to live in Rome but then came down with tuberculosis. His long illness, includ- ing a painful year in a Swiss sanatorium, kept him away from the Greek civil war, which otherwise, one would imagine, might have been irresistible. He did, however, turn up in Budapest in October 1956 for the brief, tragic uprising against the Russians. One hardly needs to say which side he took. It was at this time, the late Fifties, that Kemp wrote three volumes of memoirs that cry out for republication. From authorship it was a small step to journalism, of course as a war correspondent, and back again to Indo- china. He went as a reporter for, of all papers, the News of the World. He was around Vietnam and Laos, on and off, for as long as the Americans, and longer. All these expeditions put a strain on the second marriage, which ended, amicably. He gave up drink for a while, and now takes nothing stronger than beer. Some heart trouble responded well to surgery.

During the last decade Kemp launched again into journalism, for the Spectator, visiting Czechoslovakia, El Salvador and Ian Smith's Rhodesia. His host there, Rowlinson Carter, was rather taken aback when Kemp expressed the desire to go on a parachute drop with the Selous Scouts, and still more to be asked if it was socially acceptable at the Umtali Club to wear tennis bags. Some of Kemp's friends, who do not cover the whole spectrum of views politically, were in turn surprised when he wrote an article praising Robert Mugabe. When last heard of, in Costa Rica, Kemp was full of admiration for Eden Pastora, the Nicaraguan guerrilla, who is a man of the Left. He did not think so well of the Contras he met in Honduras. But at least, in Tegucigalpa, the beer was good.

This is the last in our series of profiles of survivors. A short series on travellers will begin soon.

Previous page

Previous page