Notebook

Last week Thomas Szasz was in London. Not surprisingly, on the day that most of our papers decided that the naming of Princess Anne's baby was the main news story, his visit was scarcely reported. This is a pity since he does not often come here; and since he is in my own humble but firm view not only the most important psychiatric thinker since Freud, but more to the point, a social and political thinker of the first order. I suspect that Dr Szasz is not much read. His seminal The Myth of Mental Illness is out of print, though The Second Sin, the brilliant, epigrammatic summary of his thought, is in paperback. He is certainly not much understood: I have grown bored of explaining to people who haven't bothered to work it out what he means by 'Mental illness is a metaphor'. And when he is understood he is not much liked. Too many people now have come to accept in its various guises the 'nanny state', or the 'therapeutic state' as Szasz calls it, which controls their medical treatment, including psychiatric, treatment; which says what stimulants they may or may not ingest; which for that matter makes them wear car seat-belts. No one wants to hear the ancient truth that 'life is an arduous and tragic struggle; and that what we call "sanity"...ltas a great deal to do with competence,. with integrity...and with Modesty and patience... acquired through silence and suffering'. Least of all when it comes from an unrepentant Millite who believes that the free choice to do harm or good to oneself, unrestricted by others, is the basis of human liberty.

Szasz was speaking at a seminar organised by the 'Citizens' Committee on Human Rights', which protests against the compulsory admission to mental hospitals under the 1959 Mental Health Act, a worthy cause if ever there was one. However, the Committee is a front for the 'Church of Scientology', and my immediate reaction was, Non tali auxilio. . I put this to Szasz who answered with characteristically ruthless logic that he had no illusions about the Scientologists, but that he had more than once defended them against arbitrary attempts to suppress them. He is, of course, right. However much we may instinctively loathe certain organisations we must protect their right to behave as they wish within the law. A new campaign is now being worked up against the Unification Church, or Moon cult. Now, it is no doubt very unpleasant that young people should learn that 'Jesus taught us that we should hate our father and mother' and should be encouraged to give up their worldly goods to the cult. But clever, silly, late adolescents have always been susceptible to this sort of thing (ten years ago at Oxford the boobies all joined something called the Process). And until Mr Paul Rose MP can find evidence of criminal behaviour by the Mooners (Moonies? Moonists?) I suggest that he might observe a period of silence.

Yet another nannyish crusade is being started, this time by the Temperance Council of the Christian Churches, under its new general secretary, the Rev Kenneth Lawton, This turbulent priest regards alcoholism as the 'primary social disease of the age'. He is trying to persuade the no less egregious Mr David Ennals to start a 'campaign in favour of moderate drinking'. Mr Lawton wishes to atone for his authorship of a churches' report on sex ten years ago which advocated a 'permissive situation ethic'. He now thinks he was wrong and that 'people are not generally mature enough to use such freedom'. I can't say that I give Mr Lawton much chance of success in his aim to establish a 'drug-free culture with. . .nonalcoholic meeting places, alternative social customs'. And they wonder why we drink. Contemplating the Roses, Ennalses and Lawtons one can only cry with Chesterton: Is that the last of them? 0 Lord, Will someone take me to a pub?

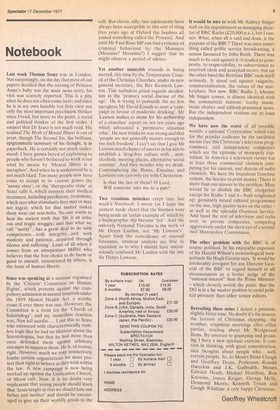

Two vexatious mistakes crept into last week's Notebook. I wrote (as I hope the context made clear) that the firemen were being made an 'unfair example of' which by a haplographic slip became 'fair'. And the unlovely National Threatre is the work of Mr Denys Lasdun, not 'Mr Lowson's'. Apart from the coincidence of unusual forename, amateur analysts are free to speculate as to why I should have unconsciously confused Mr Lasdun with the late Sir Denys Lowson. It would be nice to wish Mr Aubrey Singer well on his appointment as managing director of BBC Radio (£20,000p.a.), but I cannot. What, when all is said and done, is the purpose of the BBC? There was once something called public service broadcasting, a notion favoured by John Reith. There was much to be said against it: it tended to pomposity, to respectability, to subservience to received ideas and accepted mores; but on the other hand the Reithian BBC took itself seriously. It stood out against vulgarity, commercialisation, the values of the marketplace. Not now. BBC Radio 2, whence Mr Singer comes, is almost identical with the commercial stations: trashy music, inane chatter and tabloid-presented news. But the independent stations are at least independent.

We have now the worst of all possible worlds: a national 'Corporation' which vies for the popular audience by the tawdriest means (see this Christmas's television programmes), and independent companies which are the epitome of monopoly capitalism. In America a television viewer has at least three commercial channels competing for his custom, and dozens of radio channels. We have the iniquitous franchise system, the licence to print money. There is more than one answer to the problem. Mine would be to abolish the BBC altogether except for Radio 3 and 4 — both toughened up: genuinely mixed cultural programmes on the one, high quality news on the other— as well as the splendid Overseas Service. And hand the rest of television and radio over to private companies, competing aggressively under the stern eye of a revitalised Monopolies Commission.

The other problem with the BBC is of course political. In his enjoyable exposure of Sir Harold Wilson's terminological inexactitude Sir Hugh Greene says, 'It would be intolerably arrogant for any Director General of the BBC to regard himself in all circumstances as a better judge of the "national interest" than the Prime Minister? — which cleverly avoids the point: that the DG is in a far weaker position to avoid political pressure than other senior editors.

Rereading these notes I detect a petulant, slightly bitter tone. No doubt it's the season: the horrors of Christmas shopping, the weather, crarulous mornings after office• parties, reading about Mr Wedgwood Benn. By contrast to grumping and groaning I have a new spiritual exercise. It consists in thinking, with great concentration, nice thoughts about people who. . .well, certain people. So, to Messrs Brian Clough and Geoffrey Drain, Professors Ronald Dworkin and J.K. Galbraith, Messrs Edward Heath, Michael Heseltine, Ron Knowles, James Kruger, George Melly, Desmond Morris, Kenneth Tynan and Gough Whitlam: a very happy Christmas,

Geoffrey Wheatcroft

Previous page

Previous page