Grounds for cautious optimism

Robert Oakeshott

HIGHER THAN HOPE: THE AUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY OF NELSON MANDELA by Fatima Meer

Hamish Hamilton, £15.99, pp. 425

If Nelson Mandela was an Afrikaner rather than an African politician, we should know him not by his first name but by his initials. These, we learn on page 43 of Fatima Meer's 'authorised biography' of the world's most famous sometime political prisoner, are N.D.R. N.D.R.M.'s re- ported characterisation of the historic 2 February speech of the South African President, F. W. de Klerk, was notably generous and, in marked contrast to some other comments, quite ungrudging and unqualified. He called it 'bold and courageous'. That must be a good first omen. For whether South Africa can now find an even relatively peaceful path through to majority rule will depend more than a little on the relationship which develops between N.D.R.M. and F. W. de K. Of course it will also depend on how far these two captains succeed in controlling the inescapably violent minorities in the black and white communities.

Despite the shortcomings of Higher than Hope, the picture of N.D.R.M. which emerges from it seems to me to be plausi- ble and persuasive as well as predictably positive. Given that the author is a close friend of her subject and that she has been involved in the struggle against apartheid for at least a generation, it would be expecting too much to look for a critical approach. But though it is no doubt unfashionable and perhaps unacceptably naive to be optimistic about black African politicians, I would myself bet quite heavi- ly on N.D.R.M. The jacket quotes a judgment about him offered by the Commonwealth's so-called Eminent Per- sons Group in 1987: We found him unmarked by arty trace of bitterness despite his long imprisonment. His overriding concern was for the welfare of all races in South Africa in a just society; he longed to be allowed to contribute to the process of reconciliation.

I hope I won't seem to be trivialising a serious ;ssue if I propose a bet of a good lunch to the Spectator's literary editor that

my optimism about N.D.R.M. will stand up fairly well a year from now. I propose that bet with cautious confidence because of a combination of his family background, of the unusually honorable record of the African National Congress, anyway for most of its life and especially under Chief Luthuli in the 1950s and early 1960s; and thirdly because of the manifest quality of many of his close friends, some still living, some now dead. To deal with the last point first, I would mention, among Europeans, Bram Fisher, Alan Paton and David Astor; and among Africans not only his fellow sometime political prisoner, Walter Sisulu, but his fellow Fort Hare graduate, Seretse Khama.

Like Seretse Khama's, N.D.R.M's fami- ly is aristocratic, indeed royal: when, in 1978, his daughter Zeni took as her hus- band one of the Swazi royal princes, she was not marrying above her station. It is plausible to suppose that like •the first President of Botswana, Nelson Mandela owes to his family background his sense of public service — and his self-confidence — as well as his university education.

The parallels with Seretse Khama go further. At the 1963 Rivonia trial, from which his continuous detention dates, Mandela declared his 'great respect for British political institutions and for the country's system of justice', and he went on: 'I regard the British Parliament as the most democratic institution in the world'. In many ways his political values, like Seretse Khama's, come across as those of a good old-fashioned Liberal.

But it would probably be more accurate to describe N.D.R.M. as a social liberal, for from the ANC and from the ethical Fabianism which substantially inspired it in the 1940s and 1950s, when he served his political apprenticeship, he must have ac- quired stronger sympathies with the under- dog and a stronger belief in the benefits of government intervention in the economy than is normal with orthodox Liberals. Indeed shortly before the Rivonia trial he endorsed the ANC's so-called 'Freedom Charter'. That was a policy paper which called, among other things, for taking into Public ownership the 'commanding heights' of the South African economy.

And that brings me on to the last, and admittedly most problematic ingredient in the mix of influences which must have shaped the values and attitudes of N.D.R.M. — the South African Commun- ist Party. It is true that among the key public figures in the dramatis personae of nigher than Hope, only one, the great lawyer Bram Fisher, is explicitly identified as having belonged to the Party. But its influence on the ANC has, of course, been long and more or less continuously sus- tained. Indeed any fair-minded assessment of South African history since the 1920s would have to acknowledge invaluable Contributions by the Party to the ANC — and thus to the country — of at least two kinds: first its role in keeping the struggle against apartheid multiracial, and second its nurturing contribution in the early days and especially between the wars. It is surely true, as Professor Edward Roux, then one of the South African Communist Party's most distinguished ex-members, wrote in Time Longer than Rope in 1948, that: In South Africa the communists did pioneer work in organising the oppressed when members of other creeds and parties were not interested, and history will remember them for this.

So far as I know, N.D.R.M. has always denied being either a communist or a Marxist. But he has many times publicly acknowledged making common cause with the Party. It seems plausible to suppose that it was he himself who insisted to F. W. de' K. that the South African Communist Party, as well as the ANC, must be unbanned as one of the preconditions of his emergence from prison.

Spectator readers may see his links with the communists and his debt to them as a major ground for pessimism about the future. At least if the worry is about programmes of nationalisation, like those of the 1945 Attlee Government, I would be inclined to discount it. The Russians are known to have been advising the ANC against anything of the kind for several years.

A more serious ground for worry may be N.D.R.M.'s wife, Winnie, who has made a number of what look like errors of judg- ment in the last few years. But for what it is worth I would rate the chances of the world's most famous sometime political prisoner of controlling her as quite good. Apart from anything else, we know from a recent issue of the London Evening Stan- dard that his daily routine still includes two hours of exercise. All in all, it seems to me to be little short of providential that South Africa's blacks should be led at this time by an aristocratic social liberal and one who has kept himself remarkably fit. Spectator readers should also be encouraged by one other specific from his prison years: he not only kept himself fit; he also devoted a good deal of his limited correspondence to encouraging and even nagging his daughters in the matter of their 'A' levels and university entrance. This biography does not begin to give a rounded picture of the man. But it unquestionably supplies grounds for cau- tious optimism. Its otherwise almost meaningless title must presumably be a reference back to Edward Roux's — itself a lightly sanitised version of a West Indian slave saying: 'Time longer dan Rope'.

It is tempting, if perhaps self-indulgent, to see N.D.R.M. and F. W. de K. (or perhaps, given the former's aristocratic background, de K. F. W.) as the rival captains of two teams roughly halfway through a test match. De K. F. W., after carrying his bat to an undefeated century, declared his side's first innings closed on 2 February. N.D.R.M has been batting strongly since then and had reached 71 not out at the last rest day. The commentators are divided in their prognosis about which side will lead on the first innings and there is no consensus at all about what will happen thereafter. Yet the commentators are agreed on one point: that the disgrace- ful diversion created by the presence in the country of a crew of so-called cricket professionals under one Gatting (M.W.) should be brought to an end at once. It is a pity that N.D.R.M. did not stipulate the expulsion of Gatting and his lamentable team as one of the conditions of accepting his release. At the very least the team's matches should be expunged from the record of first-class cricket and totally ignored by Wisden.

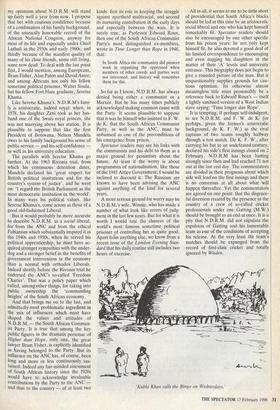

abla Khan calls the Bingo on Wednesdays.'

Previous page

Previous page