ARTS

Exhibitions

Velazquez (Museo del Prado, Madrid, till 30 March)

In the presence of genius

Giles Auty

For me, one major effect of looking at Velazquez's paintings is the way those of other artists from almost any other period pale by comparison. Wonderful breadth, colour and all-round painterly brilliance alert us that we are in the presence of great genius. Which artists can live with Velaz- quez at his finest? Rembrandt, Titian and Veronese perhaps but, at most, only a handful of others. Interestingly, Velazquez himself was not an admirer of Raphael.

By chance, Velazquez and the Prado Museum played a vital formative role in my own growing-up. Trying to describe an experience which occurred at the Prado back in 1963, I wrote later '... the main galleries, being almost empty at the time, exuded a strangely mellow and sepulchral air as the winter daylight faded rapidly in the streets outside. Standing there, I felt an extreme stillness as though I had entered some very Holy Place of Painting where the spirits of dead painters might almost speak to me if I listened attentively enough. Why, all of a sudden, did every argument for the art of the 20th century seem so completely inadequate in the face of Velazquez?'

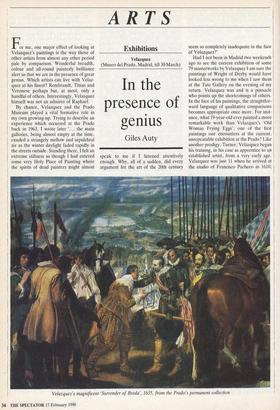

Had I not been in Madrid two weekends ago to see the current exhibition of some 79 masterworks by Velazquez I am sure the paintings of Wright of Derby would have looked less wrong to me when I saw them at the Tate Gallery on the evening of my return. Velazquez was and is a pinnacle who points up the shortcomings of others. In the face of his paintings, the straightfor- ward language of qualitative comparisons becomes appropriate once more. For inst- ance, what 19-year-old ever painted a more remarkable work than Velazquez's 'Old Woman Frying Eggs', one of the first paintings one encounters at the current, unrepeatable exhibition at the Prado? Like another prodigy, Turner, Velazquez began his training, in his case as apprentice to an established artist, from a very early age. Velazquez was just 11 when he arrived at the studio of Francisco Pacheco in 1610; Velazquez's magnificent 'Surrender of Breda', 1635, from the Prado's permanent collection by 1617 he had served his apprenticeship and could set up as an artist in his own right. Whilst we may wonder at the precise nature of the system of early 17th-century training Velazquez underwent, there was clearly something to be said for it judged simply by results. On the other hand, Velazquez seems to have possessed great natural ability from the outset. Manet described him aptly as 'le peintre des peintres'. Like his 19th-century French successor, Velazquez was fundamentally a realist, saving most of his powers of inven- tion for the practice of painting itself. Thus he was not a pictorial inventor in the manner of Rubens; his fairly early paint- ings of mythological and Old Testament subject matter, 'The Forge of Vulcan', 1630, and 'Joseph's Bloody Coat Brought to Jacob' of the same year, are both, in essence, carefully arranged studies of six male figures. Nevertheless, 'The Surrender of Breda', painted only five years later, is an absolute triumph of complex formal composition with an appearance that is at once convincing yet cool and dispassion- ate. A beautiful, bluish-green light and limpid, mildly melancholy sky illuminate the scene of post-siege devastation and contrasting human chivalry. In the flesh, this treasure from the Prado's permanent collection seems every bit as worthy of public awe as Rembrandt's so-called 'Night Watch' from the Rijksmuseum.

The current exhibition in Madrid ex- ceeds even the scope of that on view last year at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and takes place, moreover, in its true habitat. By the adding of extensive borrowings from major collections in other countries to the works held already in Spain, the exhibition's organisers present us with a unique and unrepeatable experi- ence of one of the greatest and most elegant of European masters. Here is an exhibition every true art lover should try to see. Bearing the inflated price of so many European air fares in mind, British Air- ways' current offer of an economy return to Madrid for little more than £.100 pro- vides an added incentive. Those who live in Madrid have treated the return of one of that city's more famous former inhabitants With extraordinary enthusiasm. During the first weekend of the show, visitors queued Patiently for up to five hours. Even by the time of my visit whole families were waiting in the February sunlight for two hours or more. The good humour of those waiting to see and, later, leaving the show was exemplary. I went round twice in a day and came out uplifted sufficiently to help me survive my more habitual viewing fare — which consists largely of contemporary shows — for many months to come. Velazquez was not only a great observer and draughtsman but also a consummate organiser of his picture area. We observe this latter aspect not just in full-length Portraits wherein even the precise pictorial proportions he chose have such subtle bearing on the final effect. Seldom can this have been more true than in the contrast- ing portraits of his royal patron Philip IV and his younger brother Don Carlos, both painted 1626-28. The paintings are almost identical in height but the thinner propor- tion of that of the king serves to emphasise his height and greater gravitas. In a sense, Velazquez's series of paintings of Philip IV echo the function of Rembrandt's self- portraits as we observe a man's slow decline in confidence and vigour and the effects of growing burdens in his life. Velazquez's human characterisations are generally more sober and also less arch somehow than those of Hals. There are interesting comparisons, too, in their joint abilities to render drapery with dazzling freedom and facility. Yet even Hals could not aspire to a portrait with the astonishing presence of that Velazquez painted of Juan de Pareja, his mulatto assistant.

This great Prado exhibition is a triumph both of organisation and orchestration. Skilled hanging makes the last great room, containing las Meninas', the great eques- trian portraits and other superb examples, a fitting climax to an overwhelming visual and spiritual experience. I have never left an exhibition feeling more richly fed.

Previous page

Previous page