MAMMON CHEATS THE BOMB

The IRA believes that hitting the City

weakens British resolve. Martin Vander Weyer

says money is tougher than that

Though it is a sad reflec- tion on modern life, a full- scale security alert is in effect the normal state of affairs for London's financial district. The ceasefire may rapidly come to be thought of as an unnatural lull. The phlegmat- ic attitude of those who work there, the business-driven pri- orities of their bosses and the .

high state of preparedness for attack makes the City a peculiarly pointless target for terrorism.

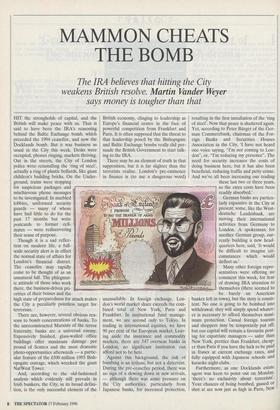

There are, however, several obvious rea- sons to bomb concentrations of banks. To the unreconstructed Marxists of the terror fraternity, banks are a universal enemy. Expensively finished, glass-walled office buildings offer maximum damage per pound of Semtex and the most dramatic photo-opportunities afterwards — a partic- ular feature of the £500 million 1993 Bish- opsgate outrage, which wrecked the giant NatWest Tower.

And, according to the old-fashioned analysis which evidently still prevails in Irish bunkers, the City, in its broad defini- tion, is the only successful element of the British economy, clinging to leadership as Europe's financial centre in the face of powerful competition from Frankfurt and Paris. It is often supposed that the threat to that leadership posed by the Bishopsgate and Baltic Exchange bombs really did per- suade the British Government to start talk- ing to the IRA.

There may be an element of truth in that supposition, but it is far slighter than the terrorists realise. London's pre-eminence in finance is (to use a dangerous word) unassailable. In foreign exchange, Lon- don's world market share exceeds the com- bined total of New York, Paris and Frankfurt. In institutional fund manage- ment, we are second only to Tokyo. In trading in international equities, we have 90 per cent of the European market. Leav- ing aside the insurance and commodity markets, there are 547 overseas banks in London; no significant institution can afford not to be here.

Against this background, the risk of bombing is an irritant, but not a deterrent. During the pre-ceasefire period, there was no sign of a slowing down in new arrivals, — although there was some pressure on the City authorities, particularly from Japanese banks, for increased protection, resulting in the first installation of the 'ring of steel'. Now that peace is shattered again. Yet, according to Peter Burger of the Ger- man Commerzbank, chairman of the For- eign Banks and Securities Houses Association in the City, 'I have not heard one voice saying, "I'm not coming to Lon- don", or, "I'm reducing my presence". The need for security increases the costs of doing business here, but it has also been beneficial, reducing traffic and petty crime. And we've all been increasing our trading these last two or three years, so the extra costs have been readily absorbed.'

German banks are particu- larly expansive in the City at present; some, like the West- deutsche Landesbank, are moving their international activities from Germany to London. A spokesman for another German group, cur- rently building a new head- quarters here, said, 'It would be difficult to imagine cir- cumstances which would deflect us.'

Many other foreign repre- sentatives were offering no • comment this week, for fear of drawing IRA attention to themselves (there seemed to be barely an American banker left in town), but the story is consis- tent. No one is going to be bombed into withdrawal: they will simply spend whatev- er is necessary to afford themselves maxi- mum protection. Casual foreign tourists and shoppers may be temporarily put off, but our capital will remain a favourite post- ing for expatriate managers — safer than New York, prettier than Frankfurt, cheap- er than Paris if you have the luck to be paid in francs at current exchange rates, and fully equipped with Japanese schools and karaoke night-clubs. Furthermore, as one Docklands estate agent was keen to point out on Monday,, 'there's no exclusivity about terrorism . Your chances of being bombed, gassed or shot at are now just as high in Paris, New York, Oklahoma, Colombo or Kasumiga- seki in central Tokyo, on the doorstep of the Japanese ministry of finance. Terrorist attack has become a random threat in every major city, some minor ones and on most forms of international transport. The level of risk has become quite unpre- dictable, but it probably increases with the concentration of financial services: for that rather twisted reason, some European cities might be happier not to take banking business away from London.

And London is generally acknowledged to be as well protected as it can be, without creating a gridlock of security checks. The City has the advantage of its own police force, now highly trained in the necessary techniques. The Canary Wharf develop- ment proper — as opposed to the nearby South Quay district which was bombed — is geographically self-contained and rela- tively secure. 'Every time I go down there, they ask for my passport,' one European banker said.

All large companies in these areas now have, at a price, anti-terrorist insurance cover, so that the £100 million-plus cost of Friday's explosion will largely come to rest with the members of Lloyd's, rather than with the blasted businesses themselves. And many of them will have been able to activate elaborately rehearsed contingency procedures: South Quay tenants like Abbey National and Midland Bank will have rapidly switched staff, telephone lines and computer links to other buildings, and car- ried on more or less as normal. Smaller businesses in the area, lacking these protec- tive arrangements, will have suffered most. It is a hideous irony, if the bomb was sup- posed to remind us of the IRA's power to damage bastions of big capitalism, that the two men who died, man Ul-haq Bashir and John Jefferies, were standing in a newsagent's shop, the humblest enterprise close to the blast.

The IRA has grasped that the killing of innocents — as in Warrington — hardens popular resolve to see them brought to submission, rather than advancing their cause through fear. So their new targets are likely to be 'economic' ones, in which death and injury can somehow be presented as incidental. The City and Docklands are obvious, and not impregnable — but the financial community is familiar with the risk, and the effect on business growth will be negligible.

If I were a terrorist seeking maximum impact on the British economy I would be looking elsewhere — at new, foreign- owned factories, for instance. But let us not be too specific. It is bad enough that we ever offered these bone-headed brutes the hand of peace; we certainly shouldn't offer them business advice as well.

'Actually, we just wanted someone to talk about road safety.'

Previous page

Previous page