A question of morale

Patrick Cosgrave

The morale of a political party is a curious, evanescent, mercurial thing: for no very tangible reason it takes sudden leaps up and down. I remember, some years ago, having a drink with Mr William Whitelaw, after he had returned &Om a long trip to the United States. The Tories were in opposition at the time and Mr Whitelaw while in America formed a very favourable view of their prospects, because in every American newspaper he read there was news of fresh disasters for Mr Wilson's government. He was desperately puzzled and depressed, poor man, when, on his return to London he found his own party in the dumps, and Labour members running around with their tails up. Neither 1 nor anybody else could give him a reasonable explanation for that state of affairs. It was not even the case, indeed, that the parliamentary performance of ministers

. had been markedly superior to that of their shadows. It had just happened, that was all. 'So we ought to treat with some caution the increase in the Tory bump of self-esteem first noticed just before the recess, and which, one could see on the first day back, had even grown a little larger over the holiday. Likewise, the shambles to which the Labour Party was reduced during the Chrysler affair is in the process of being repaired, though there is no great evidence yet of improvement in Labour spirits, in spite of the Chancellor's continued repetition of his claim that he is bringing inflation under control. The probability here is that what appear to backbenchers to be the consequences of Mr Healey's efforts — particularly increased unemployment and a falling standard of living — are exceptionally worrying to his supporters: they and the Conservatives alike know that it has too often happened that a government which succeeds in the aims it sets itself to achieve through a tightly disciplined economic policy promptly gets thrown out because people are thoroughly fed up with the effects of that policy, and the heritage of virtue thus goes to an opposition that does not deserve it.

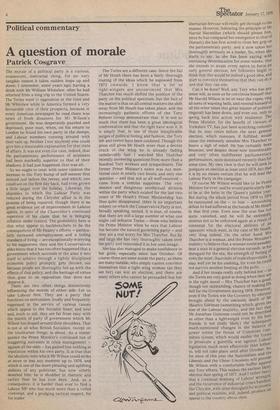

There are two other things distinctively influencing the morale of either side. Let us take Labour first. They are a party that functions on enthusiasm, loudly and frequently expressed in the service of various causes which appeal to the Socialist heart and soul and, truth to tell, they are far from easy with the mantle of party of government which Mr Wilson has draped around their shoulders. That is not at all what British Socialism, except on the totalitarian fringe, is about. As a consequence the Prime Minister's continued run of staggering successes in crisis management — against all the odds — has gained him nothing in reputation within his own party. It is true that the idealistic note which Mr Wilson could strike at more or less any moment up to 1970, and which is one of the more pleasing and uplifting abilities of any politician, has now utterly deserted him: he is shoddier in rhetoric and tactics than he has ever been. And, as a consequence, it is harder than ever to find a Labour MP who has much more than a veiled contempt, and a grudging tactical respect, for his leader. The Tories are a different case. Since the fall of Mr Heath there has been a fairly thorough routing of the ideas which he espoused from 1972 onwards. I know that a lot of right-wingers are unconvinced that Mrs Thatcher has much shifted the position of the party on the political spectrum: but the fact of the'matter is that on all central matters the shift away from Mr Heathhas taken place, and the increasingly pathetic efforts of the Tory Reform Group demonstrate that. It is not so much that there has been a great ideological confrontation and that the right have won it. It is simply that, in one of those inexplicable surges of political feeling and fashion, the Tory left and centre have been outdated. Though the press still gives Mr Heath more than a decent crack of the whip he is already fading unbelievably fast: I watched Mrs Thatcher' recently answering questions from more than a hundred Tory workers and sympathisers. The former Prime Minister's name was not men: tioned once in nearly two hours, and only one question — and that not at all welt-received — came from a centrist supporter. The very distinct and dangerous intellectual division within the party which existed for the last two years of Mr Heath's Prime Ministership has thus quite disappeared: thbre is no important subject on which the Conservative Party is not, broadly speaking, united. It is true, of course, that there are still a large number of what one might call defeatist Tories — those who believe the Prime Minister when he says that Labour has become the natural governing party — and they are a real worry for Mrs Thatcher. But by and large she has very thoroughly taken over the party and remoulded it in her own image.

She has also managed to make confidence in her grow, especially since last October. Of course there are some inside the party, as there are many outside, who simply cannot convince themselves that a right-wing woman (as they see her) can win an election; and there are many others who cannot be persuaded that her

masses. However, following the principle of Mr Harold Macmillan (which should please him, since he has compared her emergence to that of Disraeli) she has first acted to close her grip on the parliamentary party, and it now takes her thoroughly seriously as a leader. So, when she starts to say, as she has been saying with increasing determination for some weeks, that she intends to strain every nerve to force an early general election,, her followers begin to think that this would be indeed a good idea, and start to convince themselves that they can do it and that they can win.

Can it be done? Well, any Tory who has anY sense will, as soon as he convinces himself that Mr Harold Wilson is on or near the ropes, ring all sorts of warning bells, and remind himself of all the other times this great master of political ringcraft has been down, and even out, only to spring back into action with resilience. The Prime Minister, for the benefit of viewers of Yorkshire TV, has just been scotching rumours that he may retire before the next general election; which rumours, if fulfilled, would cause the eminently sensible Mrs Thatcher to heave a sigh of relief. He has certainly been bouncier, and despite those now interminable and very often indifferent parliamentary performances, more dominant recently than for some time. My own view is that he will seek to postpone an election at least until 1978, but that it is by no means certain that he will lead the Labour Party in the campaign. Of course Mr Wilson would like to be Prime Minister for ever; and he would particularly like to be at the helm in the Queen's jubilee year. But during the whole period from 1970 to 1974 he ,ruminated on the — to him — astonishing defeat he had suffered at the hands of Mr Heath in that first year. Even now the scar has not quite vanished, and he will be extremely anxious not to be unhorsed again as a result of contempt for the electoral abilities of an opponent which went, in the case of Mr Heath, very deep indeed. On the other hand Mrs Thatcher is a woman, and the Prime Minister's inability to believe that a woman could possibIY beat a man in a general election exceeds, in hise disregard for the sex, the strength of feeling c" even the most chauvinist of male chauvinists. It may well yet be his undoing, for even he could not survive another beating at the polls.

And if her troops really rally behind her — the Tories are very good at doing when they are in the right mood — Mrs Thatcher has a good' though not outstanding, chance of making fife hell for the Government during 1976. However, even if the Tories win the Coventry by-election brought about by the untimely death of Mr Maurice Edelman (something which, given the size of the Labour majority, and the fact that Mr Jonathan Guinness could not be describedt as other than a lightweight even by his best friends, is not really likely) the subsequen much-mentioned changes in the balance of power within the House of Commons committee system, which would enable the Toner to prosecute a guerrilla war against Lab(u legislation much more effectively than hitherto, will not take place until after October. Shoe, for most of this year the Nationalists andt. e Liberals and the Ulster Unionists will provid t

Mr Wilson with a comfortable buffer agains any Tory efforts. This makes the earliest likely

election date spring of 1977. And I rather fanchy that a continual draining of Labour strenngietd, and the recurrence of industrial crises had•c like Chrysler, with utter disregard for economain and political realities, will, indeed, produce appeal to the country about then.

Previous page

Previous page