SANDINISTA BOMBING

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard sees evidence of outrages against civilians

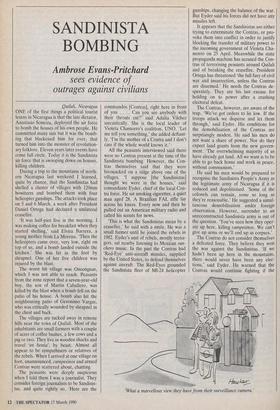

Quilali, Nicaragua ONE of the first things a political tourist learns in Nicaragua is that the late dictator, Anastasio Somoza, deployed the air force to bomb the houses of his own people. He committed many sins but it was the bomb- ing that blackened him for ever, that turned him into the monster of revolution- ary folklore. Eleven years later events have come full circle. Today it is the Sandinista air force that is swooping down on houses, killing children.

During a trip to the mountains of north- ern Nicaragua last weekend I learned, quite by chance, that the Sandinistas had shelled a cluster of villages with 120mm howitzers and bombed them with four helicopter gunships. The attacks took place on 5 and 6 March, a week after President Daniel Ortega had declared a unilateral ceasefire.

'It was half-past five in the morning. I was making coffee for breakfast when. they started shelling,' said Elvira Barrera, a young mother from La Morena. 'Then the helicopters came over, very low, right on top of us, and a bomb landed outside the kitchen.' She was hit in the foot by shrapnel. One of her five children was injured by the blast.

The worst hit village was Onconguas, which I was not able to reach. Peasants from the zone report that a seven-year-old boy, the son of Martin Caballero, was killed by the blast when a bOmb fell on the patio of his house. A bomb also hit the neighbouring patio of Geronimo Vargas, who was critically wounded by shrapnel in the chest and back.

The villages are tucked away in remote hills near the town of Quilali. Most of the inhabitants are small farmers with a couple of acres of coffee bushes, a few cows and a pig or two. They live in wooden shacks and travel 'en bestia', by beast. Almost all appear to be sympathisers or relatives of the rebels. When I arrived at one village on foot, unannounced, campesinos and armed Contras were scattered about, chatting.

The peasants were deeply suspicious when I told them I 'was a journalist. They consider foreign journalists to be Sandinis- tas, and quite rightly so. 'Here are the commandos [Contras], right here in front of you . . . Can you see anybody with their throats cut?' said Adalia Vilchez sarcastically. She is the local leader of Violeta Chamorro's coalition, UNO. 'Let me tell you something,' she added defiant- ly. 'I'm the mother of a Contra and I don't care if the whole world knows it.'

All the peasants interviewed said there were no Contras present at the time of the Sandinista bombing. However, the Con- tras themselves said that they were bivouacked on a ridge above one of the villages. 'I suppose [the Sandinistas] thought we were in the houses,' said comandante Eyder, chief of the local Con- tra force. He sat smoking cigarettes, a quiet man aged 28. A Brazilian FAL rifle lay across his knees. Every now and then he pulled out an American military radio and called his scouts for news.

'This is what the Sandinistas mean by a ceasefire,' he said with a smile. He was a small farmer until he joined the rebels in 1982. Eyder's unit of rebels, mostly teena- gers, sat nearby listening to Mexican ran- chero music. In the past the Contras had 'Red-Eye' anti-aircraft missiles, supplied by the United States, to defend themselves against aircraft. The Red-Eyes grounded the Sandinista fleet of MI-24 helicopter gunships, changing the balance of the war. But Eyder said his forces did not have any missiles left.

It appears that the Sandinistas are either trying to exterminate the Contras, or pro- voke them into conflict in order to justify blocking the transfer of military power to the incoming government of Violeta Cha- morro on 25 April. Meanwhile the state propaganda machine has accused the Con- tras of terrorising peasants around Quilali and of breaking the ceasefire. PreSident Ortega has threatened 'the full fury of civil war and insurrection, unless the Contras are disarmed.' He needs the Contras de- sperately. They are his last excuse for holding on to power after a crushing electoral defeat.

The Contras, however, are aware of the trap. 'We've got orders to lie low. If the troops attack we disperse and let them through,' said Eyder. His conditions for the demobilisation of the Contras are surprisingly modest. He said his men do not want a share of power. Nor do they expect land grants from the new govern- ment. 'The overwhelming majority of us have already got land. All we want is to be able to go back home and work in peace, without communism.'

He said his men would be prepared to recognise the Sandinista People's Army as the legitimate army of Nicaragua if it is reduced and depoliticised. 'Some of the colonels can remain, some so long as they're reasonable.' He suggested a simul- taneous demobilisation under foreign observation. However, surrender to an unreconstructed Sandinista army is out of the question. 'You've seen how they oper- ate up here, killing campesinos. We can't give up arms or we'll end up as corpses.'

The Contras do not consider themselves a defeated force. They believe they won the war against the Sandinistas. 'If we hadn't been up here in the mountains, there would never have been any elec- tions,' said Eyder. He warned that the Contras would continue fighting if the 'What a marvellous view they have rom their surveillance camera.' Sandinistas try to hold on to power, indirectly, through control over the armed forces and party cadres equipped with AK-47 assault rifles. Not even the United States can tell them what to do. 'We haven't had military aid for two years and we're still intact. We're ready to keep going until there's no more communism in Nicaragua.'

A stretch of beautiful green woodlands lay between the rebels and the army. As I crossed back into government territory a battalion of Sandinista troops were mobil- ised in full combat gear. They too were teenagers. Some of them waved and grin- ned as I went past.

The Sandinista commanding officer in Quilali, an army major, was a striking contrast to his opposite number across the lines. He was jovial, loquacious, and edu- cated. Before joining the Sandinistas in 1978 he had been an architecture student. `The last thing I ever expected was to end up as an army officer,' he said, his great beefy frame swinging back and forth in a rocking-chair.

His manner was a cross between a student intellectual and a yuppie. It was deceptive. Not realising that I had already spoken to the wounded, he said there had been no bombing of villages. 'You are misinformed. We haven't used helicopters in this region for two years.' Pressed on the details, he admitted that helicopters might have been used to pick up wounded. Finally he said: 'Maybe some of our pilots were shot 'at and fired back to defend themselves.'

He insisted that civilians had not been hurt. 'Look, bombing houses, that kind of thing, it happened under Somoza, but we'd never do a thing like that.'

The major said the army had not violated the ceasefire. 'Our troops are in static, defensive positions. They're not deployed for combat.' Shortly after I went out of his office, heavy shooting erupted in the distance. It sounded as if the second offensive had begun.

Previous page

Previous page