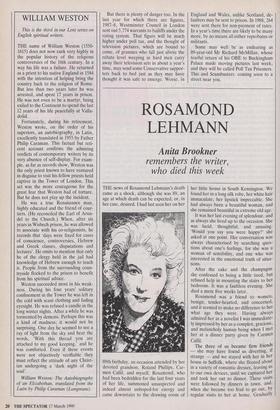

ROSAMOND LEHMANN

Anita Brookner remembers the writer, who died this week

THE news of Rosamond Lehmann's death came as a shock, although she was 89, an age at which death can be expected, or, in her case, desired. I had last seen her on her 89th birthday, an occasion attended by her devoted grandson, Roland Phillips, Car- men Callil, and myself. Rosamond, who had been bedridden for the last four years of her life, summoned unsuspected and indeed almost unhoped-for energy and came downstairs to the drawing room of her little house in South Kensington. We found her in a long silk robe, her white hair immaculate, her lipstick impeccable. She had always been a beautiful woman, and she remained beautiful in extreme old age.

It was her last evening of splendour, and as always she lived up to the occasion. She was lucid, thoughtful, and amusing. `Would you say you were happy?' she asked at one point. Her conversation was always characterised by searching ques- tions about one's feelings, for she was a woman of sensibility, and one who was interested in the emotional truth of situa- tions.

After the cake and the champagne she confessed to being a little tired, but refused help in mounting the stairs to her bedroom. It was a faultless evening. She died a mere five weeks later.

Rosamond was a friend to women, benign, tender-hearted, and concerned, and it seemed to make no difference to her what age they were. Having always admired her as a novelist I was immediate- ly impressed by her as a complex, gracious, and melancholy human being when I met her at a dinner party given by Carmen Callil.

The three of us became firm friends — she may have found us diverting, if strange — and we stayed with her in her house in Suffolk, where she floated about in a variety of romantic dresses, leaving us to our own devices, until we captured her and took her out to dinner. These visits were followed by dinners in town, and, when she became too frail to go out, by regular visits to her at home. Gradually death began to attract her, and eventually she longed for it. Since the death of her daughter, Sally, she had believed ardently in the existence of a further world and another life, of which she was confident that she had received intimations. To see Sally again was her dearest wish and her most constant hope. By the time she took to her bed she was already losing her sight, and could no longer read. Although wearied beyond endurance I believe that she was not entirely unhappy. Sometimes she would go back into the past, and sometimes, startled, she would speak of people whom she could not possibly have known. At the end she was completely herself, as if the divagations of those endless days had been mere figments of our imagination. She died quickly and quietly at home.

Rosamond was such an impressive per- son that it was an effort to remember that she was also a novelist in the grand tradition, and, more than this, an innova- tor, the first writer to filter her stones through a woman's feelings and percep- tions. She succeeds in giving a unique account of the world seen through femi- nine eyes, and this she manages better than Virginia Woolf, whom she knew, ever did.

Her greatest attribute is her straightfor- wardness, her candour: this gives her writing an air of ardour, and of youth, yet her stories are tragic. They are of course love stories, complicated, sophisticated, perhaps bitter; they have to do with innocence, hope, betrayal, disappoint- ment. Her second greatest attribute is her extraordinarily flexible style, which can modulate from formality to informality, and which has the inestimable virtue of perpetual clarity. It is perhaps seen at its finest in Invitation to the Waltz. She can also shock, as The Weather in the Streets was to prove. As befits a true original, she left no followers, although, strangely, Simone de Beauvoir was to 'acknowledge her as an influence. She was in fact far in advance of most other female novelists, both among her contemporaries and those who came after, following, or rather stumbling, in her wake.

Her method was a strange one, and speaks volumes for the degree of uncon- scious life that went into her books. She once told me that she never planned what she would write, or how she would write it: something just happened — the conjunc- tion of time and memory, perhaps — and she would sit down and produce a novel. And I never worried about whether or not I should write another,' she told me. 'I just went on with my life, and one day a novel would tap me on the shoulder. And I knew it would always be like that. There was no need for me to interfere or rack my brains. The book would either come along or not, as the case might be. There was nothing I could do about it.' Are you writing?' she would ask me. 'No, not at the moment.' It will be all right, you'll see. One will come

along.' I never had her confidence that this would happen; in any case, I never had her gift. But if I said I had started something she would lift her beautiful hands and silently clasp them. I dedicated Hotel du lac to her because I hoped it might be the kind of novel she would find to her taste. When I wrote to her, asking if she would accept the dedication, she wrote back, in her pretty Edwardian hand, Will I just!'

It was a deep source of pleasure to her that she was so respected by the French. Dusty Answer (Poussieres) has never been out of print in France, and is read by young and old alike. Perhaps they think that an emotionally articulate Englishwoman is a

phenomenon, and indeed Rosamond's case is unique. There was no confusion in her, no malice, no self-deception. She possessed a strange brooding tenderness, eternally preoccupied by love and its anx- ieties. In society she never spoke of her work: I doubt if she thought of it as work so much as some sort of visitation. She believed firmly in those things which can- not be proved. With her painfully acquired certainties — for that degree of experience does not come cheaply — she was that very real thing, a tower of strength. I shall miss her very much, as will the many people, known and unknown, who read her and remain in her debt.

Previous page

Previous page