ARTS

Exhibitions 1

A kind of humility

Christopher Howse

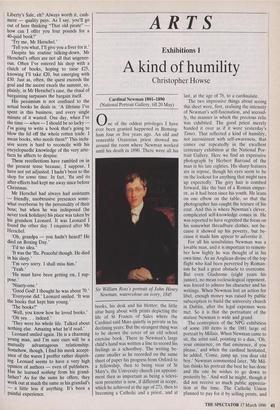

Cardinal Newman 1801-1890 (National Portrait Gallery, till 20 May) 0 ne of the oddest privileges I have ever been granted happened in Birming- ham four or five years ago. An old and venerable Oratorian priest showed me around the room where Newman worked until his death in 1890. There were all his Sir William Ross's portrait of John Henry Newman, watercolour on ivory, 1845 books, his desk and his blotter; the little altar hung about with prints depicting the life of St Francis of Sales where the Cardinal said Mass quietly in private in his declining years. But the strangest thing was to be shown the cover of an old school exercise book. There in Newman's large child's hand was written a line to record his feelings as a schoolboy. The writing be- came smaller as he recorded on the same sheet of paper his progress from Oxford to a fellowship, then to being vicar of St Mary's, the University church (an appoint- ment then as important as being a televi- sion presenter is now, if different in scope, which he achieved at the age of 27), then to becoming a Catholic and a priest, and at last, at the age of 78, to a cardinalate.

The two impressive things about seeing this sheet were, first, realising the intensity of Newman's self-fascination, and second- ly, the manner in which the precious relic was exhibited. The good priest merely handed it over as if it were yesterday's Times. That reflected a kind of humility, not inconsistent with self-awareness, that comes out repeatedly in the excellent centenary exhibition at the National Por- trait Gallery. Here we find an expressive photograph by Herbert Barraud of the man in his late eighties. His sharp features are in repose, though his eyes seem to be on the lookout for anything that might turn up expectedly. The grey hair is combed forward, like the bust of a Roman emper- or, as it had been since his youth. He leans on one elbow on the table, so that the photographer has caught the texture of his coat. And this is where Newman's clever, complicated self-knowledge comes in. He was reported to have regretted the focus on his somewhat threadbare clothes, not be- cause it showed up his poverty, but be- cause it made him appear to advertise it.

For all his sensibilities Newman was a lovable man, and it is important to remem- ber how highly he was thought of in his own time. As an Anglican divine of the top flight who had been perverted by Roman- ism he had a great obstacle to overcome. But even Gladstone (eight years his junior), no mean ecclesiological opponent, was forced to admire his character and his writings. When Newman lost an action for libel, enough money was raised by public subscription to build the university church in Dublin, after the legal expenses were met. So it is that the portraiture of the mature Newman is wide and grand.

The centrepiece of the NPG exhibition of some 180 items is the 1881 large oil portrait by Millais. When Newman came to sit, the artist said, pointing to a dais, `Oh, your eminence, on that eminence, if you please,' and when the cardinal hesitated, he added, 'Come, jump up, you dear old boy.' Newman commented later, 'Mr Mil- lais thinks his portrait the best he has done and the one he wishes to go down to posterity by.' And well he might, though it did not receive so much public apprecia- tion at the time. The Catholic Union planned to pay for it by selling prints, and then to present the painting to the National Portrait Gallery. But the prints did not sell, and the Duke of Norfolk had to save matters by buying the picture. His heir finally relinquished it to the gallery on his death in 1981.

There are things less splendid but more moving in the current show. There is an amateur painting of Newman and his dear friend Ambrose St John as Oratorian neophytes in Rome the year after New- man's conversion. It is by Maria Giberne, one of his many female admirers, and, it seems, one of the more strong- charactered, judging by her unflinching self-portrait, also in the exhibition, done in her sixties when she had been a nun for some years. And there is a watercolour of the young Gerard Manley Hopkins (whom Newman received into the Church).

If we, as we prepare to leave the 20th century, are beginning to understand the Victorian era a little better than Strachey and his imitators, then Newman is a useful window into that world. The exhibition catalogue (NPG, £9.95) by Dr Susan Fois- ter is a good supplement to the admirable recent biography by Ian Ker (OUP). But it is not the same as going to see Newman's viola, or the crozier he never needed, or the early photographs of the gin distillery (with a door marked 'Passage for British spirits') that he turned into the Birming- ham Oratory.

Previous page

Previous page