Exhibitions 2

Alison Watt

(The Scottish Gallery, London, till 31 March) Eliot Hodgkin 1905-1987: Painter and Collector (Hazlitt, Gooden & Fox, till 10 April)

Oddly enough

Giles Auty

In April 1987 Alison Watt won the very grown-up £10,000 John Player/National Portrait Gallery Award not long after outgrowing her short trousers. I was pre- sent at the ceremony and, not for the first time in such matters, was not in entire agreement with the judges' verdict. However, others, less cautious than I, rushed to their typewriters to hail a new- found prodigy. Nearly three years later, we get the chance to see how right or wrong we may all have been as 22 new paintings by the now 25-year-old Miss Watt are set before us at the Scottish Gallery, London (28 Cork Street, WI). With the clamour of last June's London acclaim for the equally youthful Scottish artist Stephen Conroy ringing still in their ears, artists seeking comparable success may reflect how indis- pensable it is to be young and Scottish at this hour. Both Watt and Conroy studied at Glasgow School of Art, which can lay claim also to such earlier high-flying ex- students as Steven Campbell, Peter How- son and Adrian Wiszniewski.

Alison Watt's paintings are predomi- nantly pale in hue and, except when they are portraits of other people, are basically portraits of herself doing singular or sym- bolic things with buckets, pitchers, ewers and bath-tubs. Miss Watt's culture, like that of Southern India, seems to be a very watery one. The artist represents herself wryly and none too flatteringly, elongating her features and wearing an expression suggesting slight but persistent toothache. Do not gather from the foregoing that I dislike or dismiss these paintings. Far from it. Most are cleverly constructed and quite decently painted, certainly by the stan- dards of our time. Miss Watt's multiple self-portraits do strange-seeming things with their rather stiff-looking hands. Perhaps she is making an amusing allusion to early Gothic art? In a work entitled 'The Loved One' the artist prepares to karate- chop a teacup having previously dispensed with her paint-brush ingeniously by tucking it into her hair. What does this all mean?

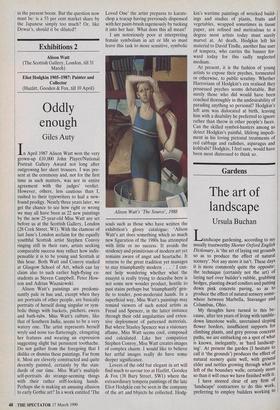

I am notoriously poor at interpreting female symbolism in art or life so must leave this task to more sensitive, symbolic Alison Watt's The Source', 1988 souls such as those who have written the exhibition's glossy catalogue: 'Alison Watt's art does something which so much new figuration of the 1980s has attempted with little or no success. It avoids the stridency and primitivism of modern art yet remains aware of angst and heartache. It returns to the great tradition yet manages to stay triumphantly modern . . I can- not help wondering whether what the essayist is really trying to describe here is not some new wonder product, hostile to past stains perhaps but 'triumphantly' gen- tle to tender, post-modernist hands. In a superficial way, Miss Watt's paintings may remind viewers of such noted artists as Freud and Spencer, in the latter instance through their odd angularities and exten- sive deployment of patterned materials. But where Stanley Spencer was a visionary aflame, Miss Watt seems cool, composed and calculated. Like her compatriot Stephen Conroy, Miss Watt creates images of complex charm. I would like to believe her artful images really do have some deeper significance.

Lovers of the odd but elegant in art will find much to savour too at Hazlitt, Gooden & Fox (38 Bury Street, SW1) where the extraordinary tempera paintings of the late Eliot Hodgkin can be seen in the company of the art and objects he collected. Hodg- kin's wartime paintings of wrecked build- ings and studies of plants, fruits and vegetables, wrapped sometimes in tissue paper, are refined and meticulous to a degree most artists today must surely marvel at. At death, Hodgkin left his material to David Tindle, another fine user of tempera, who carries the banner for- ward today for this sadly neglected medium.

At present, it is the fashion of young artists to expose their psyches, tormented or otherwise, to public scrutiny. Whether Harrovians of Hodgkin's era realised they possessed psyches seems debatable. But surely those who did would have been coached thoroughly in the undesirability of parading anything so personal? Hodgkin's left arm was dislocated at birth, leaving him with a disability he preferred to ignore rather than throw in other people's faces. Can the skilled symbol-hunters among us detect Hodgkin's painful, lifelong impedi- ment in his loving pictorial treatments of red cabbage and radishes, asparagus and kohlrabi? Hodgkin, I feel sure, would have been most distressed to think so.

Previous page

Previous page