Irritable Powell syndrome

Bevis Hillier

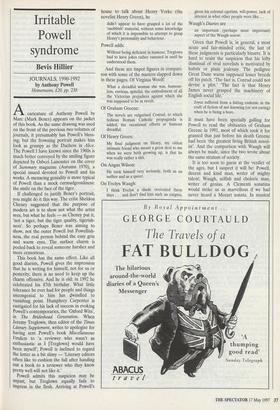

JOURNALS, 1990-1992 by Anthony Powell Heinemann, £20, pp. 238 Acaricature of Anthony Powell by Marc (Mark Boxer) appears on the jacket of this book. As the same drawing was used on the front of the previous two volumes of journals, it presumably has Powell's bless- ing; but the frowning portrait makes him look as grumpy as the Duchess in Alice. The Powell I have known since the 1960s is much better conveyed by the smiling figure depicted by Osbert Lancaster on the cover of Summary magazine (Autumn 1970), a special issued devoted to Powell and his works. A menacing geniality is more typical of Powell than a mock curmudgeonliness: the smile on the face of the tiger.

If challenged to justify Boxer's portrait, you might do it this way. The critic Sheldon Cheney suggested that the purpose of modern art is to show not what the artist sees, but what he feels — as Cheney put it, 'not a tiger, but the tiger quality, tigerish- ness'. So perhaps Boxer was aiming to show, not the outer Powell but Powellish- ness, the real person behind the easy grin and warm eyes. The surface charm is peeled back to reveal someone harsher and more censorious.

This book has the same effect. Like all good diarists, Powell gives the impression that he is writing for himself, not for us or posterity; there is no need to keep up the charm offensive. And he is old: in 1992 he celebrated his 87th birthday. What little tolerance he ever had for people and things uncongenial to him has dwindled to vanishing point. Humphrey Carpenter is castigated for his lack of success in evoking Powell's contemporaries, the 'Oxford Wits', in The Brideshead Generation. When Jeremy Treglown, then editor of the Times Literary Supplement, writes to apologise for having sent Powell's book Miscellaneous Verdicts to 'a reviewer who wasn't as enthusiastic as I [Treglown] would have been myself, Powell is inclined to regard the letter as a bit slimy — 'Literary editors often like to cushion the fall after handing out a book to a reviewer who they know pretty well will not like it.'

Powell admits this suspicion may be unjust; but Treglown equally fails to Impress in the flesh. Arriving at Powell's house to talk about Henry Yorke (the novelist Henry Green), he

didn't appear to have grasped a lot of the 'snobbish' material, without some knowledge of which it is impossible to attempt to grasp Henry's personality and behaviour.

Powell adds:

Without being deficient in humour, Treglown had to have jokes rather rammed in until he understood them.

And these are tinpot figures in compari- son with some of the masters slapped down in these pages. Of Virginia Woolf:

What a dreadful woman she was, humour- less, envious, spiteful, the embodiment of all the Victorian prejudices against which she was supposed to be in revolt.

Of Graham Greene:

The novels are vulgarised Conrad, to which tedious Roman Catholic propaganda is added, the occasional efforts at humour dreadful.

Of Henry Green:

My final judgment on Henry, my oldest intimate friend who meant a great deal to me when we were both growing up, is that he was really rather a shit.

On Angus Wilson:

He took himself very seriously, both as an author and as a queer.

On Evelyn Waugh:

I think Evelyn a shade overrated these days . . . and don't find him such an enigma, given his colossal egotism, will-power, lack of interest in what other people were like. ..

Waugh's Diaries are

an important (perhaps most important) aspect of the Waugh oeuvre.

Given that Powell is, in general, a most acute and fair-minded critic, the last of these judgments is particularly bizarre. It is hard to resist the suspicion that his lofty dismissal of rival novelists is motivated by hubris or plain jealousy. The pedigree Great Dane warns supposed lesser breeds off his patch. 'The fact is, Conrad could not devise a plot.' The fact is that Henry James never grasped the machinery of English social life.'

Joyce suffered from a failing endemic in the craft of fiction of not knowing (or not caring) when he is being a bore.

It must have been specially galling for Powell to read the obituaries of Graham Greene in 1991, most of which took it for granted that just before his death Greene had been 'the greatest living British novel- ist'. And the comparison with Waugh will always be made, since the two wrote about the same stratum of society.

It is too soon to guess at the verdict of the ages, but I suspect it will be: Powell, decent and kind man, writer of mighty talent; Waugh, selfish and choleric man, writer of genius. A Clementi sonatina would strike us as marvellous if we had never heard a Mozart sonata. In musical terms, Powell's novels are closer to opera — aria-like set-pieces, such as the pouring of sugar on Widmerpool's head, joined together by stretches of dullish recitative. With Waugh the juice never runs out. Powell's greatest achievement, perhaps, has been to restore ambition to the British novel in his A Dance to the Music of Time sequence; but there he courts a more formidable comparison. Inevitably he is labelled a poor man's Proust — though he does his best to see him off, too, in these pages:

Sex transposition begins to show awkward- ness with the entry of Albertine. The little band, as such, might be girls, but their behaviour, conversation, always sounds more like boys . . Over and above this one is struck by perpetual emphasis on Marcel's popularity, charm, good looks, women who fall for him, confidences given him by `great aristocrats' of both sexes.

Why is it that Waugh's characters, even when grotesque caricatures, engage our interest, even sympathy, while we don't care if Powell's end up in a mincing machine? Why is the snobbery of Proust's and Waugh's novels more palatable and funnier than that of Powell's? The answers lie in Powell's detachment. This trait was immortally hit off in an entry to a literary competition in which the challenge was to parody a Powell novel. The winning entry contained a line something like this: `Across the room, at Lady Elspeth's party, I caught sight of Deirdre, to whom, I recalled, I had once been married.'

The detachment gives him some extraordinary advantages. He observes everything, remembers everything. Each fragment of experience is assimilated, like a speck of food being engulfed by the two groping pseudopodia of an amoeba. His most famous line is 'Books do furnish a room', the title of the 1971 volume of the Dance sequence. The hilarious slogan is confidently ascribed to him in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. But in fact it first appeared more than 40 years earlier, in Cherwell, the Oxford University magazine of 2 March 1929. In a column headed `Sayings of the Week' it was attributed to Mr G. E. Coke — a future director of the Royal Academy of music and chairman of the Rio Tinto Company. (Coke died in 1990.) Powell was no longer at Oxford in 1929 but somehow this gem of gaucherie reached him and was sucked into his vora- cious vacuum bag.

I have experienced this process of absorption at first hand. Reading the open- ing paragraph of Powell's 1986 novel, The Fisher King (no relation whatever to Terry Gilliam's 1992 film of the same title), I was half startled, half flattered to find that it was loosely based on the opening of an article I had contributed to Alan Coren's Punch five months earlier about leaving England to work in America. A compari- son of the two passages shows Powell's pro- cess of transmutation at work:

Punch (27 November 1985): I felt like a Greek king going into exile. `No Garrick Club! No London Library!' I wailed to Catherine Bennett of the Mail on Sunday on the transatlantic telephone. `But, Bevis, that was your life!' she said.

The Fisher King (April 1986): Exile is the wound of kingship. When someone, recently returned from a transatlantic business trip, spoke of seeing a man on crutches taking photographs in the back streets of Oregon City, the rumour at once spread that Saul Henchman had settled in America.

That is a good example of how Powell doctors his material in the novels, broaden- ing the particular into the general and adding a touch of the transcendental, per- haps too a touch of the portentous. The process works even better in his volumes of reminiscences, grouped under the odd title, To Keep the Ball Rolling. Powell is one of the great autobiographers: that, it seems to me, rather than a novelist, is what he was born to be. But here, in the Journals, the raw morsels of experience are laid out for us. There is none of the contrivance of the novels and memoirs. It is like seeing Shel- ley plain or Freya stark.

Some of the morsels are mysteriously missing. The biggest public stir about Powell in the three years covered by this book was his resigning as lead book review- er of the Daily Telegraph in 1990 after Auberon Waugh slanged his collected book reviews, Miscellaneous Verdicts, in the Sunday Telegraph (27 May 1990). Waugh not only ridiculed the reviews, declaring Powell's literary style 'abominable' and censuring his use of 'the diffident double negative' and of 'dissociative inverted commas'; he also attacked Dance as 'an early, upmarket soap opera', adding that in giving the illusion of understanding English society, Dance was 'one of the cruellest practical jokes ever played by a Welshman'.

Private Eye had a field day over Powell's flouncing-out. 'Top Novelist Quits in Shock Review Drama' was the headline in its issue of 8 June 1990:

The world of books was rocked to its founda- tions today when Britain's most famous novelist, Sir Anthony Powell, stormed out of the coveted lead-reviewer slot on the Daily Telegraph, following a savage review of his latest book of collected book reviews, A Lot of Old Book Reviews, by the enfant terrible of British journalism, Mr Auberon Wasp ...

Said Sir Anthony from his West Country mansion, The Laundry: `This is the biggest insult I have ever received . . . ' But Wasp, 62, speaking last night from his West Country mansion, Combe Dancing, was unrepentant. 'Powell was a friend of my father's, but I don't see why that should stand in the way of my saying that he is a tremendous old bore.'

Powell was still smarting from the Waugh assault when I visited him in Somerset on 22 June 1990 — a visit record- ed in these journals. I remember confessing that I had not seen the offending review. Powell asked if I would like to. I said that I would, but that I felt rather like the Scot- tish (Government) minister who was invit- ed by Margaret and Denis Thatcher to accompany them to the satirical show Any- one for Denis? — I wouldn't know whether to laugh or keep a straight face.

Of all this great literary-world brouhaha there is no mention in the book. The only faint spoor of it is found in the entry for 6 July 1990: 'A sweet letter from Selina Hast- ings, expressing regret that I was leaving the Telegraph . . . ' Of his reason for leaving the paper there is no indication, in a foot- note or anywhere else. What explains this hole in the book? Was Powell so trauma- tised by the episode that he could not bring himself to write about it? Or did he write about it but censored that passage so as not to expose his wounded feelings? Or did he write about Auberon Waugh so venomous- ly that the libel lawyers crossed the words out? There is a tiny clue. The index, under `Auberon Waugh', refers us to page 49 the page on which Lady Selina Hastings's condolences are noted. But on page 49 we find no mention of Auberon Waugh. Hercule Poirot conclusion: there was previ- ously a mention of Waugh which was dis- creetly removed at proof stage, after the index was done. 0 Wasp, where is thy sting?

What the book does contain are all the elements that have made the previous volumes such an entertaining read. First, Powell's only rarely quiescent sense of humour. When his granddaughter Georgia is poisoned by a Chinese take-away, he notes, 'equivalent of attempted suicide'. (Surely even the most politically correct will not class this wokery-mockery as racist?) Disturbed in the bath by a tele- phone call from a French journalist, he takes the call, 'wrapped in a towel, feeling rather like Marat'. An encounter between Powell and his niece's husband, Harold Pinter, inspires the funniest passage in the book: There is always a slight sense of tension with Harold, and when I told him that one of Dracula's hide-outs in England had been at Sidcup (destination of the Tramp [in Pinter's play The Caretaker]), he did not laugh as much as did Antonia.

There are many delicatessen for the con- noisseur of Powell snobbery to enjoy, though nothing quite as flagrant as his reproducing, in the last volume, the Hon- ours list in the Times that announced his CH — his transparent purpose being to show that, in the list, his gong took prece- dence over mere knighthoods. But he is pleased to learn that Monet was elected a member of the Beefsteak Club. After root- ing round in a second-hand bookshop in Frome he comes away with

Contarini Fleming by 'the Right Honourable B. Disraeli', with an Earl's coronet stamped in gold on the cover.

Marcus Scriven, then on the Londoner's Diary of the Standard, turns out to be

an eminently presentable young man (Hadley, Christ Church, regular Captain Welsh Guards):

But Powell's snobbery is more romantic than pernicious. After making a Radio 3 recording with Paul Bailey, he writes:

Really a great relief to be interviewed by an intelligent man like Bailey . . . I rather think he said somewhere that his father was a dust- , man.

Jonathan Stedall, who made television films of John Betjeman during the poet's last years, has said that he regrets not film- ing him a year or two earlier. But he feels there was one advantage to leaving the filming so late. Through infirmity, Betje- man's defences were down:

He was almost totally unselfconscious in front of the camera. The performer in him was largely laid aside . . . He became more transparent, more truly what he was in essence.

Powell was not decrepit in the early 1990s, though a prostate operation laid him pretty low. But his defences were down. We see him here as unselfconscious as he ever gets. Concentrated essence of Powell smells good but has some corrosive proper- ties.

As Edith Sitwell once said to me [he writes on 3 June 1990], 'It's wonderful being able to make people so angry when one is so old. '

Previous page

Previous page