Exhibitions

Gilbert & George: Fundamental Pictures (Sonnabend and Lehmann Maupin, New York, till 28 June)

What an achievement!

Roger Kimball

It is one of the oddities of being an art critic today that so much of what one is called to comment upon qualifies as art only in a technical or honorific sense. The relevant definition of 'art' in my dictionary refers to 'the production of the beautiful in a graphic or plastic medium' How much 'cutting-edge' contemporary art has any- thing to do with beauty? (How much even has to do with 'a graphic or plastic medi- um'?) To ask such questions is to highlight the fact that much of what is regarded as art today occupies a place in human experi- ence that is not merely indifferent but downright antithetical to beauty it is ugly, yes, and also perverse, disgusting, banal, tendentious, blasphemous, silly and vapid. The real novelty of contemporary art the part of it that counts as 'avant-garde', anyway — is that it manages to be so many of these things at the same time: ugly and silly, disgusting and vapid, perverse and banal. In a way, it is quite an achievement — though not, of course, an artistic achievement.

I had occasion to muse about such mat- ters recently when I went to see the exhibi- tion of new pictures by Gilbert & George at two trendy SoHo galleries in New York. I hasten to acknowledge that, for anyone interested in art, too little cannot be said about this pair of industrious self-promot- ers. But for those interested in the psy- chopathology of culture, Gilbert & George present a noteworthy specimen — an unusually malignant boil or pustule on the countenance of contemporary art.

For those fortunate souls unacquainted with Gilbert & George, it is enough to explain that, like so many bad things, they emerged on the art scene as performance artists in the late 1960s. At first, they pro- claimed themselves 'living sculptures'. Dressed in identical suits, they would stand on pedestals pantomiming to a popular tune for hours on end. In the early 1970s, they began to exhibit black and white photo-montages, usually with themselves and other young men as the main subjects.

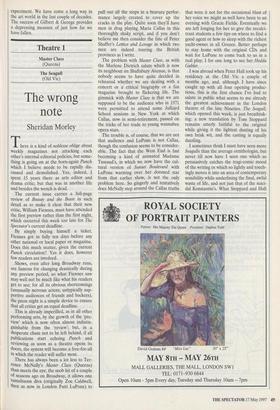

By the mid-1970s they hit upon the for- mula they have followed ever since. They create large, brightly coloured square or rectangular photo-montages by joining together many individually framed pictures. The result is a kind of scatological Pop Art. Images of the two men, usually naked, sometimes in various obscene postures, occupy the foreground of most of the pic- tures, some of which cover an entire wall. The background usually consists of photo- graphic images of bodily fluids or waste products, magnified beyond recognition except when the waste product is excre- ment: then the image is merely grotesquely enlarged. Fond of using dirty words, Gilbert & George tend to title their works after the bodily effluvia they portray.

It is part of Gilbert & George's act to pose as moralists whose art is wrestling with deep existential and religious ques- tions. 'We believe our art can form morali- ty, in our time,' George tells us in one typical statement. 'Our art is based on human life. All the important subjects of existence are involved,' Gilbert says in 'Spat On' by Gilbert & George, 1996 another. They act like drunken pornogra- phers, but tell us they are engaged in a holy mission. It's what Marxists used to call increasing the contradictions.

It is a sign of the degraded times we live in that this sort of thing has been a wild commercial success. In 1986, Gilbert & George won the Turner Prize. In the last several years journalists regularly describe them as England's most famous and richest contemporary artists. Pictures in the New York exhibition are on sale for between $40,000 and $120,000.

It is hardly surprising that words like `shocking', 'transgressive', and 'controver- sial' are regularly used to describe — and to praise — Gilbert & George's work. What really is shocking, however — and I use the word in the old, negative sense is the extent to which important critics have fallen over themselves to celebrate this lat- est expression of narcissistic nihilism. Already in the mid-1980s, Simon Wilson wrote that Gilbert & George had 'come to be seen as being among the leading artists of their generation' and that the young men who populate their pictures are `equivalents, performing the same function in art, of the classicising male figures of Michelangelo and Raphael'.

In 1995, when Gilbert & George exhibit- ed 'The Naked Shit Pictures' in London, Richard Dorment, writing in the Daily Tele- graph, invoked the Isenheim altarpiece as a precedent. John McEwen, in the Sunday Telegraph, spoke of their 'self-sacrifice for a higher cause, which is purposely moral and indeed Christian'. Not to be outdone, David Sylvester, in the Guardian, wrote that 'these pictures have a plenitude, as if they were Renaissance pictures of male nudes in action'. And in the catalogue for the present exhibition, Robert Rosenblum really takes flight: 'Brilliantly transforming the visible word into emblems of the spirit, Gilbert & George create from these micro- scopic facts an unprecedented heraldry that, in a wild mutation of the Stations of the Cross, fuses body and soul, life and death. Once again, they have crossed a new threshold, opening unfamiliar gates of eter- nity.'

It might be tempting to dismiss this as harmless journalistic persiflage: nonsense, of course, but merely what one expects of critics these days. I cannot agree. The pre- posterous praise critics have lavished upon Gilbert & George is a sign of deep cultural malaise. After all, without the collusion of critics, Gilbert & George would have remained where they belong, as a footnote to late 20th-century cultural pathology. Instead, they are celebrated as important artists. Walking up Greene Street with me after seeing Gilbert & George at the Lehmann Maupin Gallery, a friend remarked, 'Think of how much had to hap- pen in our culture for Gilbert & George to be accepted as art.' And not only accepted, but accepted without qualm or protest indeed, embraced as a beneficent spiritual experiment. We have come a long way in the art world in the last couple of decades. The success of Gilbert & George provides a depressing measure of just how far we have fallen.

Previous page

Previous page