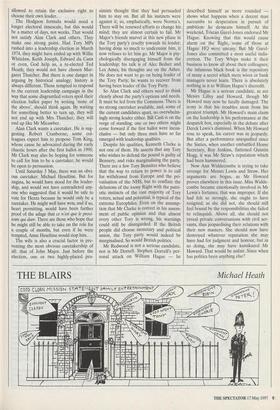

NEW LEADER, NEW VOTING?

An electoral college, a caretaker leader.

Bruce Anderson reports on the plots and

schemes of the Tories in opposition

MARX wrote that history repeats itself: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. In the light of the party leadership campaigns of 1990 and 1997, many Tory MPs would now agree with the old boy.

For those closely involved, leadership campaigns are enjoyable. After the Major campaign of 1990 was all over, the minis- ters returned to their official duties with all the enthusiasm of small boys returning to school at the beginning of term; leadership campaigning was much more fun. So it is this time — to the exasperation of every Tory MP who is not closely involved. One former minister describes the campaign as a beauty contest between the ugly sisters.

As usual, Alan Clark is best at capturing the mood. The Tory party is like a newly- occupied country, he says. All the power structures have been shattered; even the cur- rency is now worthless. Yet the leadership teams are behaving as if the old symbols of authority still had meaning. `You should know that my man has always admired your work; he'd definitely have you as a front-bench spokesman' — all this said, as it were, to individuals only interested in working out how to find bread and potatoes.

There is pressure for postponing the leadership election. Alan Clark wants to wait until November; the former Transport Secretary, George Young, has talked about a two-year delay. There is even more pres- sure for widening the franchise. Most of the 164 Tory MPs know that their prestige has never stood lower. If, despite this, they insisted on their sole right to choose a new leader, the party in the country would revolt. One of the new leader's first duties might be to attend the Scottish party con- ference in late June; if Scots Tories had had no say in his election, some of them would express their feelings. Traditionally, new Tory leaders present themselves to be ratified by a meeting of the party's voluntary side; up to now, a challenge would have been as unthinkable as a challenge at a coro- nation. This time, however, unless the fran- chise is widened, there will be a challenge.

The umbrella organisation of the volun- tary wing of the Conservative party is the National Union (of Conservative and Unionist Associations). Its chairman, Robin Hodgson, is a reformer. Even before the election, he was convinced of the need for a reconstruction of the party machine, including a wider franchise for the election of the leader. He is not challenging the MPs' primacy; he accepts that one of the leader's principal functions is to dominate the Commons, and that it is for MPs to judge a fellow MP's ability to do this. So only MPs could nominate a leadership can- didate, but once the runners and riders had been saddled in the Commons, the Nation- al Union should form 20 per cent of the electoral college; its votes distributed to each candidate according to their perfor- mance in a ballot of all party members.

At present, there is no minimum entrance fee for joining the Tory party, and hardly anyone is minded to change that. Francis Maude — the former minister who is Michael Howard's campaign manager thinks that there should be a new category of voting member, paying, say, £25 a year with concessionary rates for the old and the very young. That strikes me as a good idea, but Mr Hodgson wants every member to be able to vote for the leadership.

There is one problem: a ballot of party members might require George Young's two years to organise. But Mr Hodgson has an interim solution; a National Union electoral college of 894 constituency chairmen, area functionaries et al. who would reflect the party's membership.

By Tuesday evening, all the leadership candidates except Michael Howard had accepted Mr Hodgson's proposals, with greater or lesser enthusiasm. The Howard team recognise the need for change in the longer term, but believe that the imminent ballot should be held on the old system. They have other things on their mind at the moment; when they do address the matter, they will realise that only an election conducted under the Hodgson formula could possi- bly be regarded as legitimate.

There is a second problem with the proposal for a wider franchise. If the House of Commons gave up its monopoly of the choice of leader, why should the senior branch of the Tory Parliamentary party not recover via democracy the rights it lost with the pass- ing of the old magic circle? Lords Cran- borne and Strathclyde would settle for the Tory peers having 10 per cent of the vote; they will probably have their way. Then there is a further, unwelcome, complexity. This is one of those moments when the rest of the Tory party remembers, to its dismay, that it has Euro-MPs. They will want a say; hardly anyone else apart from Ken Clarke will want to give them one, unless and until rather more of them are worthy of being called Tories. There is a general feeling that they should be fobbed off, by being allowed to retain the exclusive right to choose their own leader.

The Hodgson formula would need a longer electoral timescale, but this would be a matter of days, not weeks. That would not satisfy Alan Clark and others. They make one strong point. Had Tory MPs rushed into a leadership election in March 1974, they might have ended up with Willie Whitelaw, Keith Joseph, Edward du Cann or even, God help us, a re-elected Ted Heath; they would not have chosen Mar- garet Thatcher. But there is one danger in arguing by historical analogy; history is always different. Those tempted to respond to the current leadership campaign in the way that some disgruntled voters spoil their election ballot paper by writing 'none of the above', should think again. By waiting for something better to turn up, they will not end up with Mrs Thatcher; they will end up like Mr Micawber.

Alan Clark wants a caretaker. He is sug- gesting Robert Cranborne; some col- leagues expect him to propose Tom King, whose cause he advocated during the early chaotic hours after the first ballot in 1990. Mr Clark may also be hoping for someone to call for him to be a caretaker; he would be open to persuasion.

Until Saturday 3 May, there was an obvi- ous caretaker: Michael Heseltine. But for angina, he would have stood for the leader- ship, and would not have contradicted any- one who suggested that it would be safe to vote for Hezza because he would only be a caretaker. He might well have won, and if so, heart permitting, would have been further proof of the adage that ce n'est que le provi- soire qui duce. There are those who hope that he might still be able to take on the role for a couple of months, but even if he were tempted, Anne Heseltine would stop him.

The wife is also a crucial factor in pre- venting the most obvious caretakership of all: that of John Major. Just before the election, one or two highly-placed pes- simists thought that they had persuaded him to stay on. But all his instincts were against it; so, emphatically, were Norma's. There will be renewed efforts to change his mind; they are almost certain to fail. Mr Major's friends marvel at this new phase in the Tory party's cruelty towards its leader; having done so much to undermine him, it now refuses to let him go. Mr Major is psy- chologically disengaging himself from the leadership; his talk is of Alec Bedser and Les Ames, his thoughts are on the Ashes. He does not want to go on being leader of the Tory Party; he wants to recover from having been leader of the Tory Party.

So Alan Clark and others need to think clearly about the party's options and needs. It must be led from the Commons. There is no strong caretaker available, and, some of the current candidates apart, no overwhelm- ingly strong leader either. Bill Cash is on the verge of standing; one or two others might come forward if the first ballot were incon- clusive — but only three men have so far emerged with leadership qualities.

Despite his qualities, Kenneth Clarke is not one of them. He asserts that any Tory who wishes to defend the pound is guilty of Bennery, and risks marginalising the party. There are a few Tory Bennites who believe that the way to return to power is to call for withdrawal from Europe and the pri- vatisation of the NHS, but to conflate the delusions of the loony Right with the patri- otic instincts of the vast majority of Tory voters, actual and potential, is typical of the extreme Europhiles. Even on the assump- tion that Mr Clarke is correct in his assess- ment of public opinion and that almost every other Tory is wrong, his warnings could still be disregarded. If the British people did choose monetary and political union, the Tory party would indeed be marginalised. So would British politics.

Mr Redwood is not a serious candidate, nor is Mr Dorrell. Stephen Dorrell's per- sonal attack on William Hague — he described himself as more rounded shows what happens when a decent man succumbs to desperation in pursuit of ambition: he demeans himself. At the weekend, Tristan Garel-Jones endorsed Mr Hague. Knowing that this would cause alarm on the Right, some of those at Hague HQ were uneasy. But Mr Garel- Jones also committed a most useful indis- cretion. The Tory Whips make it their business to know all about their colleagues; the infamous black book is the repository of many a secret which mere wives or bank managers never learn. There is absolutely nothing in it to William Hague's discredit.

Mr Hague is a serious candidate, as are Messrs Lilley and Howard, though Mr Howard may now be fatally damaged. The irony is that his troubles stem from his greatest triumph. Mr Howard's main claim on the leadership is his performance at the despatch box, especially in the debate after Derek Lewis's dismissal. When Mr Howard rose to speak, his career was in jeopardy. But after a performance unequalled since the Sixties, when another embattled Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, flattened Quintin Hogg, it was Mr Straw's reputation which had been hammered.

Now Ann Widdecombe is trying to take revenge for Messrs Lewis and Straw. Her arguments are bogus, as Mr Howard proves elsewhere in this issue. Miss Widde- combe became emotionally involved in Mr Lewis's fortunes; that was improper. If she had felt so strongly, she ought to have resigned; as she did not, she should still feel bound by the responsibilities she failed to relinquish. Above all, she should not reveal private conversations with civil ser- vants, thus jeopardising their relations with their new masters. She should now have destroyed whatever reputation she may have had for judgment and honour, but in so doing, she may have kamikazed Mr Howard. That would be unfair. Since when has politics been anything else?

Previous page

Previous page