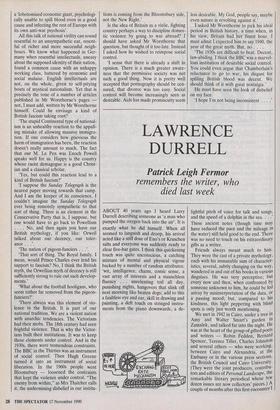

LAWRENCE DURRELL

Patrick Leigh Fermor remembers the writer, who died last week

ABOUT 40 years ago I heard Larry Durrell describing someone as `a man who pumped the oxygen back into the air'. It is exactly what he did himself. When all seemed to languish and droop, his arrival acted like a stiff dose of Eno's or Kruschen salts and everyone was suddenly ready to clear five-bar gates. I think this quickening touch was quite unconscious, a catching mixture of mental and physical vigour backed by a number of random attributes: `wit, intelligence, charm, comic sense, a vast array of interests and a staunchless fluency . . unrelenting toil all day, punishing nights, hangovers that slink off next morning like beaten dogs; add to this a faultless eye and ear, skill in drawing and painting, a deft touch on stringed instru- ments from the piano downwards, a de- lightful pitch of voice for talk and songs, and the speed of a dolphin in the sea. . . These ancient notes (though time may have reduced the pace and the mileage in the water) still held good to the end. There was no need to touch on his extraordinary gifts as a writer.

Friends always meant much to him- They were the cast of a private mythology, each with his immutable sum of character- istics; several, subtly changing on the way, wandered in and out of his books in various disguises. He was very perceptive; but every now and then, when confronted by someone unknown to him, he could be led astray by misinterpretation of the data, or a passing mood; but, compared to his kindness, this light peppering with blind spots is only just worth mentioning.

We met in 1942 in Cairo, under a tree in Amy and Walter Smart's garden in Zamalek, and talked far into the night. He was at the heart of the group of gifted poets and writers — Robin Fedden, Bernard Spencer, Terence Tiller, Charles Johnston and several others — who were working, between Cairo and Alexandria, at the Embassy or in the various press sections, the British Council and Cairo University- (They were the joint producers, contribu- tors and editors of Personal Landscape, the remarkable literary periodical whose few dozen issues are now collectors' pieces.) A couple of months after this first encounter I met another old friend of Larry's when I joined Xan Fielding in German-occupied Crete; there, in caves and goat-folds, Xan told me about The Black Book, and followed it up with a score of anecdotes about their pre-war life in Athens.

When the war was over, I read Pros- pero's Cell in its actual literary setting of Corfu, during that first miraculous post- war summer, and soon Xan and I and the Corn Goddess (as Larry called her; we eventually married) went to see Larry on Rhodes. We found him settled into the Villa Cleobolus among old Turkish tomb- stones and elaborate black-and-white peb- ble mosaics dappled with the shadows of leaves. It was an amazing sojourn, spent in talk and music and feasting. Strange things always happened in his company, and one afternoon, in the ruins of ancient Camirus, wine-sprung curiosity set the four of us crawling on hands and knees through the bat-infested warren of underground water- conduits. We climbed out covered in drop- pings and dust and cobwebs, and our exploration reached an extraordinary cli- max when Xan leaped a couple of yards from the coping of a high ruined wall onto an Ionic column 12 feet high. It rocked frighteningly on its stylobate for several seconds. At last, as we watched with held breath, it became static, with its new arrival poised on the capitol — for some reason, but most appropriately, with no- thing on — like a flying stylite.

Reflections on a Marine Venus, which captures these Rhodian months, was an admirable successor to Prospero's Cell. Each island gave birth to a book and a new sheaf of poems, and they made one look at Greece with a different glance and the same excitement and zest as the Tyrrhene coast and Calabria prompted in the pages of Norman Douglas. We visited him later in Cyprus and the midnight echoes of the vaults of Bellepaix Abbey resound in the memory still.

In Athens we shared many of the same friends — George Katsimbalis chiefly, and George Seferis and Niko Hadjikyrnkon- Ghika; indeed, most of the cast of The Colossus of Maroussi — but, by the time we too became inhabitants of Greece, he had taken wing for Provence. He lived briefly in Sommieres and then settled on the edge of the garrigue above Nimes in a house which he seemed to be building, very capably, with his own hands. Like a marine Vulcan, he hammered out the successors to Justine; you could almost see the sparks flying as Balthazar, Mountolive, and Clea were thrown sizzling from the forge. A marvellous new Alexandria was being fitted over the old and then peopled by his amazing denizens.

His next house lay a dozen miles to the west of the old on the banks of the Vidourle, and here, under the scaling plane trees with the clank of boules seldom out of earshot, the task continued; after a couple of decades, he seemed to have taken root at last. It was a good place to halt on the way to Greece and draw corks in and catch up. If it had only been closer to the Peloponnese, where these lines are being written! These joyful reunions didn't happen often enough. Still, it was hearten- ing to think that there Larry was, at his desk, with vigour and imagination undim- med, surrounded with glory and, I hope, with a carafe of wine cooling close by.

As though to prove undiminished im- agination and vigour, this morning's post has brought a new publication by Faber not yet out. It is about his beloved Provence, and it is called Caesar's Vast Ghost. It Is full of the stories, landscapes, comedy, history, heresies, animals, food, drink and songs of the Midi, as though he had planned to leave us on a note of hope and cheer.

Previous page

Previous page