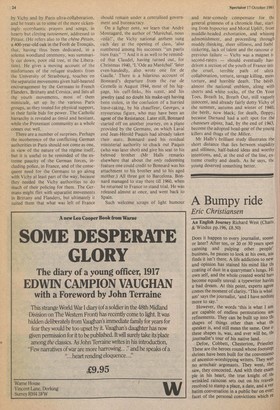

A Bumpy ride

Eric Christiansen

An English Journey Richard West (Chatt( Windus pp.196, £8.50) Does it happen to every journalist, soone or later? After ten, or 20 or 30 years spell canning and pulping other people' business, he pauses to look at his own, ant finds it isn't there. A life addiction to new and opinion has stained his mind like tilt coating of dust in a quarryman's lungs. Hi own self, and the whole created world hot become equally unreal: a typewriter havim a bad dream. At this point, experts agree comes the moment of clarity. 'This is what am' says the journalist, 'and I have nothim more to say.'

However, the words 'this is what I ant are capable of endless permutations ant refinements. They can be built up into tit( shapes of things other than what tilt speaker is, and still mean the same. One o these shapes is, was, and ever will be, tilt journalist's tour of his native land.

Defoe, Cobbett, Chesterton, Priestley These are the heroes round whose footstep' shrines have been built for the convenienc( of ancestor-worshipping writers. They wet( no armchair argonauts. They went, the saw, they concocted. And with their exam pie in his heart, the true knight of th' wrinkled raincoat sets out on his travels resolved to stamp a place, a date, and a vet batim conversation in a public bar on ever: facet of the personal convictions which re main the only solid thing in a world of exhausted illusions.

The latest domestic rover needs no introduction here, for it is Richard West, one of the many African correspondents who have been pouring out the heart of darkness over the cornflakes of Spectator readers for the last decade. It could be said of him, as of Cobbett, that he would excel in any company by the breadth of his experience and by the narrowness of his sympathies, and when he decides to travel from Manchester to Manchester by way of Lowestoft, we must be prepared for a bumpy crossing.

The trouble with this cobbetting lark, by the way, is that everybody loves Cobbett, but Cobbett did not want to be loved. He wanted to teach, to be followed as a guide to political decency, common-sense, and the right way to grow potatoes. His fate was to be admired for his nonsense and passion. Now the question is, has Mr West the gift of eloquent irascibility and nothing more, or has he the power to persuade, instruct and plant potatoes?

Well, the book starts at Manchester, Which he finds a derelict dump where 'people still drink, but no longer work,' and moves on to Liverpool where 'more even than in Manchester one gets the feeling of Purpose and glory gone.' Then to the Lake District, where he meets a young victim of television who informs him that 'We are not interested here in Wordsworth, or in his torrid love affair with his sister.' Then over to Newcastle and a warning to Whitehall: 'Expect no gratitude from the Geordies, the more money you spend on them, the more they will want, the more they will make you subsidise their indolence and cantankerousness.' Durham next, the 'Home of Postal Bingo' and of labour councillors whom a publican describes as 'complete morons, pissed out of their minds most of the time.' Then to Yorkshire, including Bradford, 'a maze of ring-roads and flyovers and hideous blocks and desolation. Manchester looks almost untouched by comparison. Bradford is far worse even than Liverpool or Newcastle'. That was one month's travelling, and it inspired almost continuous vituperation. The ugliness and decrepitude of what Mr West saw would have driven him to drink, had he not foresworn hopeless intoxication before setting out. It was not only bad, it was worse than 25 years ago, and much worse than before the usurpation of Henry IV in 1399.

But why? He gives three explanations. The corruption of local government: the corruption of the Unions: and the idiocy of contemporary culture. The Queen's ministers, particularly so-called conservative ministers, have merely licensed and fostered these distempers from a distance. .Corruption really began not under Attlee In 1945, but under Macmillan 12 years and corruption takes two forms: tens of thousands of people are drawing salaries and expenses for useless jobs: and some of them have been taking bribes on top., Many, perhaps most readers of the Spectator and of 'Peter Simple' will agree with all this, and will enjoy Mr West's exposure of Northern England accordingly. The selfexposure is also very entertaining; but why should anyone else take any notice of what he says? In fact, the people of England, who are notorious for not having spoken yet, might still be moved by the sound of his mountainous disenchantment to utter the question 'What's it all in aid of?' Cobbett complained, but Cobbett thought he knew what was wrong and how to put it right. Mr West is loud in elegy, inaudible in remedy. If it is all true what he says, if every modern English institution is rotten to the roots, except the Campaign for Real Ale (and that has been infiltrated by Trotskyites), then there is really nothing to be done. Even if you force-feed 10,000 malingering civil servants with Theakston's Old Peculier, they will still have nothing useful to do and expect to be paid for doing it. And if it is not true, Mr West is no prophet. He is just one of the overmanned ENSA of respectable eccentrics which keeps the troops happy on the job.

Anyway, the journey continues in an easterly and then a southerly direction, and here Mr West finds more to praise — 'stinking rich' farmers, splendour of the countryside, splendour of Felixstowe harbour, splendid Kent opera, Norwich, Adnam's bitter, Mr Aspinall's zoos, the Royal Family, Ely and Winchester cathedrals, Clifton, a second-hand bookshop in Lichfield, and the purposeful government of King John. This is not a complete list, but from it you get a picture of what the better 'ole resembles, where it is to be found. It contains people untouched by, or emancipated from the habits of mind that have become dominant over the last 25 years, minding their own business and making it pay in defiance of unions and governments.

Mr West draws comfort from his discovery of these people and things, but only as reminders of what has been irretrievably lost elsewhere.

It would be presumptuous to pass judgment on Mr West's judgments, because they follow logically from a fear which he seems to share with a majority of his fellowcountrymen. They do not want to be conducted into an alien wilderness of innovation by morons and tricksters disguised as European MPs, Social Workers, Bishops, and Civil Servants. But the experience of the last 25 years suggests that there is very little they can do about it, and the pervading despondency of An English Journey is a faithful echo of this impotence. However, it may be some consolation to recall that this fear is very ancient, predating even the usurpation of Henry IV, not confined to England, and has never yet been wholly justified — not because the worst does not happen, but because nations have not yet proved 100 per cent efficient even in self destruction. Individuals survive, and on Mr West's evidence they are surviving now.

Previous page

Previous page