BOOKS

The last Labour PM

Jo Grimond

TIME AND CHANCE by James Callaghan

Collins, f15.95

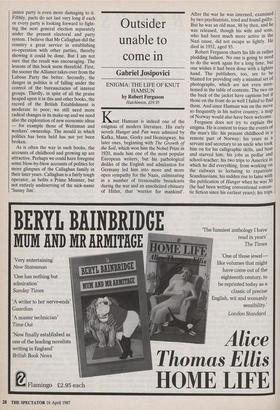

Why did Sunny Jim allow his pub- lishers to put such a preposterous dust- jacket on his autobiography? The back- ground appears to be a hell of bogus brimstone, like the back-cloth in a panto- mime from which the demon-king leaps. But in the foreground is no leaping demon but a figure compounded of one of the American Presidents of the 1920s and a dispensing chemist who has just laced a prescription with a dose of arsenic. It is very misleading both as to the character and activities of the subject. The book might indeed be more read- able with a touch of arsenic. But in these days when political abuse according to the Papers has got out of hand (though this seems an unnecessarily squeamish attitude — the only Prime Minister to be shouted down in the House of Commons was Mr Asquith by the yelping Cecils) it is rather nice to read a book in which all politicians seem to have run pretty well and all get Prizes.

Mr Callaghan filled all four great offices of state, Prime Minister, Foreign Secret- ary, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Home Secretary. I used to think that the one for which he was peculiarly suited was Prime Minister, an office which nowadays demands more of temperament than intel- lectual ability. After reading this book I am not so sure. In spite of its main drawback, Which is that like all books packed out by researchers and assistants it is too long and too detailed, certain conclusions emerge.

Mr Callaghan makes very few bows in the direction of state socialism. At home he was concerned about inflation and hoped to make the poor better off. Like his contemporaries he never brought himself to recognise that under the economic and Political system of the time the two aims were incompatible. Nevertheless, as a Chancellor of the Exchequer he probably had the right objectives. As a Foreign Secretary he at least avoided such blunders as under Mrs Thatcher and Lord Carring- ton led to the Falklands war. And as a Home Secretary he saw the importance of prison reform. At every turn of the book it becomes apparent that Britain was pushed around by international forces, yet her Establishment, Tory and Labour, clung to the illusion that she could command not only her own destiny but other people's. They much enjoyed (as they still do) hob-nobbing with the great at summit meetings. The other millstones around a Labour Prime Minister's neck were, firstly, the Trades Unions, whose leaders all Labour ministers pretend to be endowed with a divine wisdom which is not appa- rent to other people. Of course they pay for the Labour Party, which naturally has its effect — though this is not mentioned by Mr Callaghan (any more than it is men- tioned that the Labour Party's dominance in Scotland influenced their attitude to devolution). And secondly, the narking and fission-prone nature of the Labour Party itself — which proves how wise it was to split. It is time that it split again.

It is apparent that Mr Callaghan, inherit- ing a caretaker government, spent much of his time as Prime Minister manoeuvring to hold on to office. These manoeuvres are of topical interest. And it is here that I rest my case that he had certain virtues valu- able in a Prime Minister. The idea of co-operating with another party causes the Labour or Liberal parties to buck and rear like a horse asked to pass a steam- roller. Yet when faced with the need to cobble together a majority in the Com- mons if he was to stay in office, he calmly set about negotiations not only with the Liberals but with Ulster Unionists and Nationalists.

I long ago pointed out to the Liberal Party that if they were to grow in strength they would have to face co-operation with another party. I had no objection therefore in principle to the Lib-Lab pact. But I did not believe that it was worth much on the terms offered. To my mind we should have demanded electoral reform with Labour whips on to get it. I have been told since that the Labour Cabinet would probably have accepted this request but that it was never demanded by the Liberals. I am also told by Lord Mayhew (who, though no longer a member, had wide experience of the Labour Party) that so frightened of an election were the Labour Party as a whole that they would also, though kicking and screaming, have accepted it.

Now that a hung parliament is a possibil- ity let us look at what lessons are to be learned. First, initiative lies with the Prime Minister. The correct response of the Alliance to those innumerable television quizzes to which their leaders are subjected about their behaviour in a hung parlia- ment, is 'go and ask Mrs Thatcher'. She will be Prime Minister after the election, she will make the first move. The response of other parties will depend on what she does.

The next point is that not only in retrospect but in fact the Liberal and Labour leaders got on very well. Without a considerable common outlook the pact could never have started. Thirdly, it was largely compounded of a rather negative agreement to drop certain party measures and concentrate on current problems.

Fourthly, the party which is the junior partner is at a disadvantage. It does not have the civil service behind it. It is apt to get the blame without the praise. In these days when politics are more and more (for worse and worse) dominated by media headlines, the shadowy position of the junior party is even more damaging to it. Fifthly, pacts do not last very long if each or every party is looking forward to fight- ing the next general election separately under the present electoral and party system. I believe that Mr Callaghan did the country a great service in establishing co-operation with other parties, thereby showing it could be done. But I am not sure that the result was encouraging. The lessons of this book seem threefold. First, the sooner the Alliance takes over from the Labour Party the better. Secondly, the danger in politics is of falling under the control of the bureaucracies of interest groups. Thirdly, in spite of all the praise heaped upon it in this and other books, the record of the British Establishment is moderate to poor; we still need more radical changes in its make-up and we need also the exploration of new economic ideas — for example those of Weitzman and workers' ownership. The mould in which politics has been held has not yet been broken.

As is often the way in such books, the accounts of childhood and growing up are attractive. Perhaps we could have foregone some blow-by-blow accounts of politics for more glimpses of the Callaghan family in their later years. Callaghan is a fairly tough operator, as befits a Prime Minister, but not entirely undeserving of the nick-name 'Sunny Jim'.

Previous page

Previous page