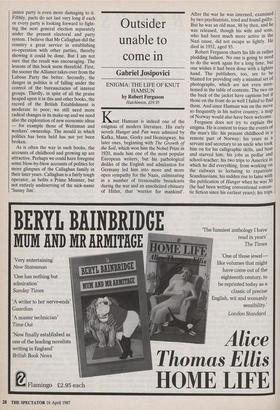

Outsider unable to come in

Gabriel Josipovici

ENIGMA: THE LIFE OF KNUT HAMSUN by Robert Ferguson

Hutchinson, f19.95

Knut Hamsun is indeed one of the enigmas of modern literature. His early novels Hunger and Pan were admired by Kafka, Mann, Gorky and Hemingway, his later ones, beginning with The Growth of the Soil, which won him the Nobel Prize in 1920, made him one of the most popular European writers; but his pathological dislike of the English and admiration for Germany led him into more and more open sympathy for the Nazis, culminating in a number of treasonable broadcasts during the war and an unsolicited obituary of Hitler, that 'warrior for mankind'.

After the war he was interned, examined by two psychiatrists, tried and found guilty. But he was an old man, 88 by then, and he was released, though his wife and sons, who had been much more active in the Nazi cause, did not escape so lightly. He died in 1952, aged 93. Robert Ferguson charts his life in rather plodding fashion. No one is going to need to do the work again for a long time, but one wishes it had been done with a lighter hand. The publishers, too, are to be blamed for providing only a minimal set of photographs, which are not even men- tioned in the table of contents. The two on the back of the jacket have captions but if those on the front do as well I failed to find them. And since Hamsun was on the move so frequently in his native country, a map of Norway would also have been welcome.

Ferguson does not try to explain the enigma. He is content to trace the events of the man's life: his peasant childhood in a remote part of Norway; his years as a servant and secretary to an uncle who took him on for his calligraphic skills, and beat and starved him; his jobs as pedlar and school-teacher; his two trips to America in which he did everything, from working on the railways to lecturing to expatriate Scandinavians; his sudden rise to fame with the publication of Hunger when he was 30 (he had been writing conventional roman- tic fiction since his earliest years); his trips to Germany and France, where he met and quarrelled with his idol Strindberg; his failed first marriage to an aristocrat; his often violent and ultimately disastrous second marriage to the actress Marie Andersen, 23 years his junior. He is under no illusions that the novels written after the first world war were greatly inferior to the earlier ones. Hamsun was always short of money and he wrote in order to make it, but, as with so many of the great 19th- century novelists, this was perhaps only a screen for a deeper compulsion. Writing, in the end, was his only love, and some- thing he simply had to do. When trying to get a new novel under way he would leave home for months on end, hiding away in remote Norwegian resorts and leaving his wife to bring up the children and look after the estate he had bought with his new- found wealth in Hamar0y. The trouble was that Balzac and Dickens and Dostoevsky had a form which would uphold them. Their work is uneven, but uneven within the course of the same book; and the strengths more than make up for the weakness. Hamsun had come too late for that. Hunger is indeed worthy of the admiration accorded it by Mann and Kafka. It is one of the great books of urban alienation; but, more important, it breaks completely with the excessive plotting of 19th-century fiction. Like Kafka's novels and Rilke's Make Laurids Brigge, it holds together through the sheer intensity of the author's vision, his sheer determination not to be deflected in pinning down his vision. As Ferguson says, it has a timeless quality which makes it as fresh today as when it was written, in 1890. It has left its mark on the work of many of today's best writers, notably Peter Handke. By con- trast, the later novels are in the style of all those popular successes of the interwar years, the novels of Feuchtwanger and Werfel and the rest.

In one of the few really sharp comments he makes in the course of this large book, Robert Ferguson suggests that the trouble was that Hamsun was a modernist, an outsider, in a country where, for good historical reasons, writers had always been public figures. The model was not Strind- berg but Bjornson, very much the 60-year- old smiling public man. And there was no way the self-taught Hamsun, with his aggressive and destructive urges, could reconcile the outsider with the public figure. He had not Yeats's profound understanding of pre-Romantic literature to help him create any equivalent to Yeats's theory of masks. As a result, he simply turned from the private to the public and lost his way, until, in the end, even his public stance, by a kind of reaction on the part of the rebel still in him, went to supporting a cause few Norwegians could accept. There were many who were glad that he had got his comeuppance in the end. For he was an unsympathetic figure, a tyrant at home and an inveterate polemicist in pub- lic, always prepared to turn on friend and foe alike. And yet there is something both moving and exhilarating about the man, about his stubbornness and his confused desire to go on doing what he had to do throughout a long life. And the world would be the poorer without Hunger.

Previous page

Previous page