The days of golden dreams have perished

Roy Kerridge

A TIME THERE WAS: MEMORIES OF RURAL LIFE IN SUSSEX by Phoebe Somers The Weald and Downland Open Air Museum, Singleton, Sussex, £6.99, pp. 79 Twenty years ago, I used to walk across the fields from Angmering to the tiny village of Poling, in West Sussex. Phoebe Somers, a cheerful no-nonsense artist and writer with a loud, confident voice that belied her bird-like appearance, lived at the end of a lane that dwindled into a muddy footpath to Lyminster of the bot- tomless pool. I would duck my head as I passed below the thatched porch and into her tiny dark cottage. Once inside, I would admire Phoebe's collection of home-cured rat-skins pinned to cards like butterflies, and her watercolours of village life in Kenya, where she once taught at a girls' school. In the back garden, beady-eyed African and Greek tortoises came shuffling to meet us. However, Phoebe Somers's main claim to local fame was her weekly essay and drawing in the West Sussex Gazette. The long, narrow flint cottage terrace in which she lived had been built for the Duke of Norfolk's farm workers. Phoebe remained on friendly terms with the old man who once lived in her house, and with her gnarled, wise or crafty neighbours. Each week she both sketched and wrote a pen- portrait of an elderly countryman or woman, and many of these pieces have at long last been gathered up and distilled into a book.

Still a good newspaper today, the West Sussex Gazette of 20 years ago approached perfection. Every Thursday, country people turned to Phoebe Somers's drawings, to the essays of John Batten on villages forgotten by Time and Progress, to the 'Mrs Paddick' column of comedy and folklore and last of all to the fine engraving of a fox that head- ed the 'Hunting Appointments' column.

These were the golden days. A time there was, indeed, when Phoebe Somers and the Victorian fox still held sway in their ducal Arundel-printed domain. Now the fox has gone to earth, and Phoebe Somers too has been forced to relinquish her column, much against her will. Recast to form a nostalgic book smelling of newly turned furrows, her columns live again between bendy covers, with old photographs added. A great deal of sympathy is aroused when miners or other manual labourers lose their livelihoods, even if large redun- dancy payments are made. But who cares when a columnist gets the boot? The idea of a campaign for justice and fair play for newspaper columnists would seem laugh- able to most people. Editors suddenly inform columnists in full flow that their column has been ended and that's that. No reason is given to the readers, and if they write in to protest, their letters are not printed. Soon the columnist becomes a non-person, forgotten by all, unless rescued by A Time There Was type of book. Colum- nists are not staff members of newspapers, and receive no compensation for dismissal, the editor-bosses conniving in the fiction that all columnists have other sources of income and 'can always manage'.

Enough grinding of axes — now to the book. Some of the country people whose reminiscences fill these pages are now dead, some of them I knew. Phoebe Somers's drawings are expressive and sharply Sussex, bright eyes set in rugged, comfortable features. Most of the accom- panying essays consist of fragments of autobiographical conversation, with the underlying theme that in the day before yesterday, before the war and before the war before that, life was harsh but people were pleasant. Nowadays it is the other way round. George Ewart Evans's books on rural Suffolk evoke the same early-morning-in-the-fields, horse-handling atmosphere.

Machinery, which made life easier for countrymen, eventually changed their nature. One of Phoebe's drawings shows a sad-faced retired hedger, George Weekes, who lived to see the hedges that were his pride and joy 'trimmed' by horrendous hedge-hacking machinery. Surveying the splintered wrecks of his hedges, he replied to an enquiry after his health: 'I'm better than I would have bin if I'd bin responsible for these 'edges!'

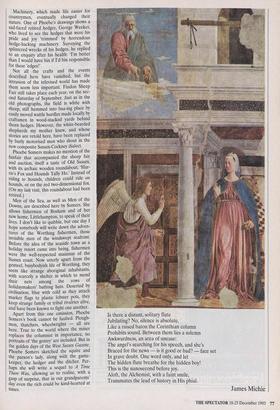

Not all the crafts and the events described here have vanished, but the Intrusion of the televised world has made them seem less important. Findon Sheep Fair still takes place each year, on the sec- ond Saturday of September. Just as in the old photographs, the field is white with sheep, still hemmed into baa-ing place by easily moved wattle hurdles made locally by craftsmen in wood-stacked yards behind thorn hedges. However, the white-bearded shepherds my mother knew, and whose stories are retold here, have been replaced by burly motorised men who shout in the new composite Sussex-Cockney dialect. Phoebe Somers makes no mention of the funfair that accompanied the sheep fair and auction, itself a taste of Old Sussex, with its archaic wooden roundabout, 'Har- ris's Fox and Hounds Tally Ho.' Instead of riding to hounds, children could ride on hounds, or on the red two-dimensional fox. (On my last visit, this roundabout had been retired.) Men of the Sea, as well as Men of the Downs, are described here by Somers. She allows fishermen of Bosham and of her new home, Littlehampton, to speak of their lives. I don't like to quibble, but one day I hope somebody will write down the adven- tures of the Worthing fishermen, those invisible men of the windswept seafront. Before the idea of the seaside town as a holiday resort came into being, fishermen were the well-respected mainstay of the Sussex coast. Now utterly apart from the genteel, busybodyish life of Worthing, they seem like strange aboriginal inhabitants, with scarcely a shelter in which to mend their nets among the rows of holidaymakers' bathing huts. Deserted by civilisation, blue with cold as they attach marker flags to plastic lobster pots, they keep strange family or tribal rivalries alive, and have been known to fight one another. Apart from this one omission, Phoebe Somers's book cannot be faulted. Plough- men, thatchers, wheelwrights — all are here. True to the world where the miner replaces the columnist in importance, no portraits of 'the gentry' are included. But in the golden days of the West Sussex Gazette, Phoebe Somers sketched the squire and the parson's lady, along with the game- keeper, the hedger and the ditcher. Per- haps she will write a sequel to A Time There Was, allowing us to realise, with a gasp of surprise, that in our grandparents' day even the rich could be kind-hearted at times. Is there a distant, solitary flute Jubilating? No, silence is absolute.

Like a raised baton the Corinthian column Prohibits sound, Between them lies a solemn Awkwardness, an area of unease: The angel's searching for his speech, and she's Braced for the news — is it good or bad? — face set In grave doubt. One word only, and let The hidden flute breathe for the hidden boy! This is the nanosecond before joy.

Aloft, the Alchemist, with a faint smile, Transmutes the lead of history in His phial.

James Michie

Previous page

Previous page