CHRISTMAS ARTS

Heritage

Small miracle in Bohemia

Jonathan Marsden on the preservation of a unique baroque private theatre

Before the war the historic South Bohemian town of Cesky Krumlov was still called Krumau and its princely owners, the Schwarzenbergs, still ran a private army and grew pineapples within the castle precinct. The 'cleansing' of the German population and nationalisation of noble houses followed swiftly afterwards. Under communism the castle became a major tourist attraction and now receives 160,000 visitors each year. Since 1966 none of them has been allowed to see its greatest archi- tectural treasure, the private theatre, set up for Prince Josef Adam of Schwarzenberg in the 1760s. In September an international conference was called by the regional State Monuments Institute and the Theatre Institute of Prague to consider the restora- tion and re-opening of the theatre.

Krumlov came to the Schwarzenbergs in 1719 by inheritance from the Eggenberg family, who had added a theatre to the Renaissance castle buildings in the 1670s. This was to be eclipsed after the succession of Prince Josef Adam (1722-82). He added a storey of baroque state rooms to the old castle and had the Swabian painter Josef Lederer cover the walls of his new ball- room with fancy-dressed figures. In his gar- den the Duke went in for mazes and grottoes, and in his summer-house — like the Empress of Russia — he had a gadget for making the dining table rise up fully laden from the floor below.

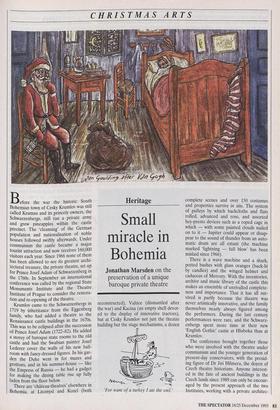

There are 'château-theatres' elsewhere in Bohemia, at Litomysl and Kozel (both reconstructed), Valtice (dismantled after the war) and Kacina (an empty shell devot- ed to the display of innovative tractors), but at Cesky Krumlov not just the theatre building but the stage mechanisms, a dozen Tor want of a turkey I ate the owl.' complete scenes and over 150 costumes and properties survive in situ. The system of pulleys by which backcloths and flats rolled, advanced and rose, and assorted hey-presto devices such as a roped cage in which — with some painted clouds nailed on to it — Jupiter could appear or disap- pear to the sound of thunder from an auto- matic drum are all extant (the machine marked 'lightning — full blow' has been mislaid since 1966).

There is a wave machine and a shark, potted bushes with glass oranges (back-lit by candles) and the winged helmet and caduceus of Mercury. With the inventories, archive and music library of the castle this makes an ensemble of unrivalled complete- ness and importance. That it has all sur- vived is partly because the theatre was never artistically innovative, and the family themselves nearly always figured among the performers. During the last century performances were rare, and the Schwarz- enbergs spent more time at their new `English Gothic' castle at Hluboka than at Krumlov.

The conference brought together those who were involved with the theatre under communism and the younger generation of present-day conservators, with the presid- ing figure of Dr Jiri Hilmera, the doyen of Czech theatre historians. Anyone interest- ed in the fate of ancient buildings in the Czech lands since 1989 can only be encour- aged by the present approach of the two Institutes, working with a private architec- tural practice and conservators. The build- ing fabric and its interior decorations have been stabilised and the chronic problem of rising damp eliminated. An earlier scheme for air-conditioning has been abandoned as too destructive to install and a solution of elegant simplicity found to counteract the habitual 95 per cent relative humidity.

Conservation of the costumes has fol- lowed the best practices for some years but is expensive, and many are in very poor condition. When the textile conservator, Alena Grendysova, came to work on the turban of a 'Turkish' costume she found it resembled an overgrown tree stump; the pathogenic fungal growths on its paper armature had to be treated with antibiotics.

The general impoverishment of the com- munist years was kind to many of Bohemia's 18th-century buildings, but at the same time the practice of repair and maintenance lost its way, and at Krumlov even those with the best intentions had to take short cuts. In the 1950s and 60s the theatre remained in sporadic use, and the stage floor and many of the original mecha- nisms were replaced or altered to meet the requirements of modern productions. At the conference this autumn the practicali- ties of recreating 'authentic' baroque per- formances in the theatre without further damage or replacement of fabric were squarely addressed. For example, the 12 backcloths painted by Jan Wetschel and Leo Merkel around 1766 will not stand repeated unrolling and replicas will have to be made for use.

There are no funds for this or for the conservation, storage and display of the originals (which will require a purpose- designed space elsewhere in the castle complex). In the context of the economic reconstruction of the Czech Republic, his- toric buildings cannot take first call on state funds, and the fruition of the plans proposed at September's conference will depend on support from abroad.

The Krumlov theatre is certainly as important as the court theatre of Drott- ningholm in Sweden, which is the only other comparable survival in Europe. It is perhaps the greatest surviving embodiment of a culture of music and performance that pervaded 18th-century Europe. If Mr Major's notion of 'a wider Europe' has any substance, especially in a year when the EC Architectural Heritage grant programme is specifically devoted to historic buildings for the performing arts, let him remember that the musicians who brought the exciting sounds of the French horn to the ears of the first audience of Handel's Water Music in 1717 were Bohemians.

Jonathan Marsden works for the National Trust.

Flats by Jan Wetschel, 1766-7, part of the magnificent baroque scenery at the private theatre in the castle at Cesky Krumlov

Previous page

Previous page