Crafts

Talking about angels

Tanya Harrod on the art of Patrick Reyntiens, a master of stained glass Just after the second world war was an optimistic moment for all the arts. It was a period that proved energetic and generous enough to accommodate a renaissance in stained glass, which, despite gifted practi- tioners like Evie Hone, Harry Clarke and Douglas Strachan, was in decline in the 1920s and sidelined in the 1930s. The late Forties, however, saw a host of conunis- sions, mostly funded by the government to repair war damage and to celebrate peace. This renaissance shaped the life of Patrick Reyntiens, a painter fresh from art school who today must be counted the senior figure in British stained glass..Reyn- tiens trained with E.J. Nuttgens in the early 1950s, received a grant to study glass in French churches and in 1952-3 was intro- duced by Penelope Betjeman to John Piper. A remarkable partnership began. There was an instant rapport, for the young Reyntiens combined craft skills in glass with an intimacy with and understanding of avant-garde art. Piper himself had been interested in glass in an antiquarian spirit since 1929 and he was conscious of the work of Rouault and a post-war Parisian figuration which made free with bold black outline, reminis- cent of the lead-lines of stained glass. Throughout the 1950s there was a happy coincidental visual reciprocity between much innovative French and British paint- ing and the potential of stained glass for colour intensity and semi-abstraction. It was a timely moment for the creation of a shared language and for the Piper/Reyn- tiens partnership and for subsequent Reyn- tiens collaborations with Cecil Collins and Ceri Richards.

Reyntiens initially translated a Piper gouache of two heads which led on to a magnificent series of joint works — the hieratic nine windows in Oundle School chapel, the reckless beauty of the Parables and Miracles at Eton College Chapel and the abstract Baptistery window at Coventry Cathedral. As Reyntiens explains:

Piper's designs were made with all the free- dom and franchise of a painter and I had to take them into my very spleen and liver and re-interpret them, very much as Rimsky Kor- sakov re-orchestrated Mussorsky. And that to me is not an illicit occupation.

These are generous, expansive thoughts about co-authorship. But then Reyntiens argues that it is only the recent marginali- sation of painting which has forced the artist to renounce the role of interpreter or as Reyntiens puts it, priest — and take up a new role as originator or solitary prophet:

Until the 18th century artists were priests; they reprocessed data which society laid at their feet and reclothed it in an aesthetic wonder. Even someone as original as Michelangelo or Raphael was reprocessing very old facts, very old data.

For Reyntiens, stained glass will always be a priestly occupation, not a prophetic one. Almost at once as a stained-glass artist Reyntiens was conscious of a paradox:

On the one hand you had the old cultural vision which was the history of art and the history of the Catholic Church (of which I am a member) going back for 2,000 years and on the other hand you had the modern move- ment. The one was decorative, figurative, didactic, historiated, allusive, reinforcing. The other believed in a tabula rasa, scientific fact, reason, no decoration, political collec- tivism of one kind or another.

Nonetheless, despite his consciousness that the decline of stained glass coincided with the coming of age of the modern world, Reyntiens's own glass has always reflected developments in contemporary painting — from his semi-abstract 'Still Life' shown in the Smithsonian British Artist Craftsmen of 1959-60 to his return in the 1980s to figurative work inspired by a whole range of resonant visual and literary sources, above all Ovid's Metamorphoses which have inspired a dazzling sequence of expressive small-scale panels.

Reyntiens is a strikingly learned artist, at home with classical literature but also one of today's finest commentators on contem- porary art. His reviews for the Tablet are notable for their sensitive visual insights and openness to the new. Characteristical- ly, he is equally familiar with the language and lore of the cinema, seeing it as replac- ing stained glass as the major public com- munications system after the Great War. Indeed Reyntiens can made out a persua- sive case for late 19th-century and Edwar- dian glass functioning as a form of visual propaganda throughout the British Empire. If necessary he can create glass that employs that Victorian vocabulary — his glass for the Great Hall at Christ Church, Oxford deliberately set out to honour and employ the language of the 19th century...

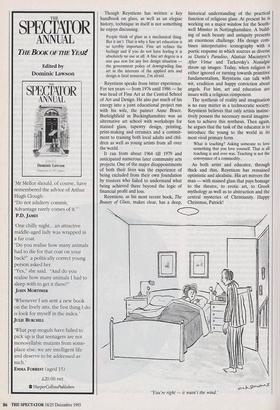

Roundel, a series of seven, 'The Circus, 1991, by Patrick Reyntiens, glazed by Bernard Becker Though Reyntiens has written a key handbook on glass, as well as an elegiac history, technique in itself is not something he enjoys discussing.

People think of glass as a mechanical thing. But it isn't. That is why a fine art education is so terribly important. Fine art refines the feelings and if you do not have feeling it is absolutely no use at all. A fine art degree is a sine qua non for any live design situation the government policy of downgrading fine art in the interests of the applied arts and design is fatal nonsense, I'm afraid.

Reyntiens speaks from bitter experience. For ten years — from 1976 until 1986 — he was head of Fine Art at the Central School of Art and Design. He also put much of his energy into a joint educational project run with his wife, the painter Anne Bruce. Burleighfield in Buckinghamshire was an alternative art school with workshops for stained glass, tapestry design, printing, print-making and ceramics and a commit- ment to training both local adults and chil- dren as well as young artists from all over the world.

It ran from about 1964 till 1979 and anticipated numerous later community arts projects. One of the major disappointments of both their lives was the experience of being excluded from their own foundation by trustees who failed to understand what being achieved there beyond the logic of financial profit and loss.

Reyntiens, as his most recent book, The Beauty of Glass, makes clear, has a deep, historical understanding of the practical i function of religious glass. At present he is working on a major window for the South- well Minster in Nottinghamshire. A build- ing of such beauty and antiquity presents an enormous challenge. His design com- bines interpretative iconography with a poetic response in which sources as diverse as Dante's Paradiso, Alastair Macintyre's After Virtue and Tarkovsky's Nostalgia throw up images. Today, when religion is either ignored or turning towards primitive fundamentalism, Reyntiens can talk with wit, erudition and happy conviction about angels. For him, art and education are issues with a religious component.

The synthesis of reality and imagination is no easy matter in a technocratic society; Reyntiens believes that only artists instinc- tively possess the necessary moral imagina- tion to achieve this synthesis. Then again, he argues that the task of the educator is to introduce the young to the world in its most vivid primary form.

What is teaching? Asking someone to love something that you love yourself. That is all teaching is and ever was. Teaching is not the conveyance of a commodity.

As both artist and educator, through thick and thin, Reyntiens has remained optimistic and idealistic. His art mirrors the man — with stained glass that pays homage to the theatre, to erotic art, to Greek mythology as well as to abstraction and the central mysteries of Christianity. Happy Christmas, Patrick!

`You're right — it wasn't the wind.'

Previous page

Previous page