siso

guDaiiildLt3

SPAIN'S FINEST CAVA

CHESS

SPAIN'S FINEST CAVA

bt13'0111)11 Lin

Annus mirabilis

Raymond Keene

THE EVENT of the year has undoubtedly been the breakaway from Fide, the World Chess Federation, by Kasparov and Short to form the Professional Chess Associa- tion. Their bold decision led to their first success, the creation of the world cham- pionship in London. Excellent progress was then made by the announcement, to a gathering of 600 players at the tournament in Oviedo earlier this month, that the PCA had been promised around seven million dollars from Intel, the computer compo- nents company, to fund their ongoing world championship cycle.

With the investment in the London match, together with this new injection of funds, it is apparent that the setting-up of the PCA has revolutionised global interest in chess and the promotion of the game. The sponsorship found this year for chess has thoroughly justified the decision by Kasparov and Short to break with the old governing body. Indeed, in comparison, the sums involved make Fide's finances look like the budget of a corner shop.

Who, on the record of the year, can now think of challenging Kasparov successful- ly? Nigel Short, of course, has gained immense experience from the cham- pionship match, and will be doubly danger- ous in the next cycle. Anand, Kamsky, Kramnik and Shirov also have their claims, while Karpov himself, as proved by his victory at Tilburg, remains a serious con- tender.

Unfortunately both Karpov and Boris Gelfand have, at the time of writing, still excluded themselves from the PCA cycle. Perhaps the new announcement of Intel funding will persuade them, at the last minute, to reverse their decision to boycott the PCA cycle, the only one, given Kaspar- ov's involvement, that can confer legiti- mate championship status.

Boris Gelfand of Russia won the Fide" Interzonal earlier this year. He is a formid- able attacking player, whose presence would be missed when the PCA Interzonal starts at Groningen tomorrow.

Gelfand —Shirov: Chalkidiki 1993; Slav Defence.

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Nf3 a6 This innocent-looking pawn move has become high fashion in the Slay. Black speculates on 5 e3 b5 6 b3 Bg4, which has been extremely successful from the black point of view. Cvitan — Bareev, played at Tilburg in November, continued 7 h3 Bxf3 8 gxf3 Nbd7 9 cxd5 cxd5 10 a4 b4 11 Net when, after 11 . . . e6, Black already had the more comfortable position. 5 Ne5 Clearly a more vigorous way of handling the positron. Alternative methods of seeking to profit from Black's unconventional handling of the opening are 5 a4 e6 6 g3 as in Ivanchuk — Shirov, also at Tilburg, or 5 c5 g6 6 Bf4 Nh5 7 Bey f6 8 Bg3, as in another Gelfand — Shirov game from Chalki- diki. 5 . . . Nbd7 6 cxd5 cxd5 7 Bf4 e6 $ e3 b5 9 Bd3 Bbl The battle lines in the opening have been clearly drawn. White's light-squared bishop on d3, aiming at Black's king, is far more effective than its black counterpart, hemmed in on b7. In compensation, however, lack has more space on the queen's flank. 10 0-0 Bel 11 a4 Trying to disturb Black's harmonious queen- side development by puncturing his pawn front. 11 b4 12 Na2 A standard manoeuvre. The knight is heading for cl in order to re-emerge on the safe square b3, blockading Black's 'b' pawn.

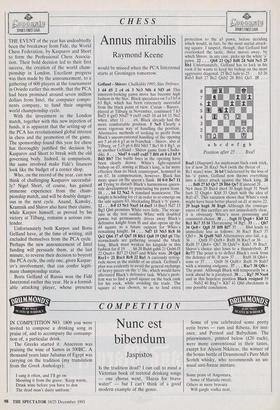

12 . . . 0-0 13 Ncl Nxe5 14 dxe5 14 Bxe5 Nd7 15 Bg3 Qb6 promises White very little. The recap- ture in the text saddles White with doubled pawns but permanently drives away Black's defensive knight from f6 and also opens up the d4 square as a future outpost for White's remaining knight. 14 . Nd7 15 Nb3 Rc8 16 Qe2 Qb6 17 a5 Qa7 18 Rfcl Qa8 19 Qh5 g6 The stormclouds are gathering around the black king. Black must weaken his kingside in this fashion for if 19 . . . h6 20 Bxh6 gxh6 21 Qxh6 f5 22 Qxe6+ Rf7 23 Qxd7 and White wins. 20 Qg4 Axel+ 21 Rxcl Rc8 22 Ral A curiously retrog- rade move in the middle of an attack. Gelfanet's plan was evidently to avoid the general exchange of heavy pieces on the 'c' file, which would have alleviated Black's defensive task. White's prob- lem was to find a good square on the back rank for his rook, while avoiding the trade. The square al was chosen, so as to lend extra protection to the a5 pawn, before deciding which would, in fact, be the most useful attack- ing square. I suspect, though, that Gelfand had overlooked the tactic, three moves away, by which Shirov, in any case, picks up the white 'a' pawn. 22 . . . Qb8 23 Qg3 Bd8 24 Nd4 Nc5 25 Bbl Unfortunately, Gelfand has to lock in his rook if he wants to keep his bishop on the most aggressive diagonal. 25 Bc2 fails to 25 . . . b3 26 Bxb3 Bab 27 Bc2 Qxb2 28 Rbl Qc3. 25 . . .

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 a bc de f gh Position after 25 . . . Bxa5 Bxa5 (Diagram) An unpleasant back-rank trick, for if now 26 RxaS Ne4 (with the threat of . . Rcl mate) wins. 26 h4 Undeterred by the loss of his 'a' pawn, Gelfand now throws everything into a direct attack against the black king. 26 . . . Bd8 27 h5 Qc7 28 Bh6 Qe7 If instead 28 . . Ne4 then 29 Bxe4 dxe4 30 hxg6 hxg6 31 Nxe6 fxe6 32 Qxg6+ Kh8 33 Qxe6 with the idea of Rdl-d7. This variation shows that White's rook might have been better placed on dl at move 22. 29 hxg6 hxg6 30 Bxg6 Although the consequ- ences of this sacrifice are not immediately clear, it is obviously White's most promising and consistent choice. 30 . . . fxg6 31 Qxg6+ Kh8 32 Rcl Rc7 33 f4 Threatening 34 BgS. 33 . . . Qh7 34 QeS+ Qg8 35 B18 Rf7 35 . . Bh4 leads to immediate loss as follows: 36 Rxc5 Rxe5 37 Qh5+ . 36 Qxd8 Nd3 Alternatives also fail, e.g. 36 . . Qxf8 37 Qxf8+ Rxf8 38 Rxc5 or 36 . . Rxf8 37 Qh4+ Qh7 38 Qxh7+ Kxh7 39 Rxc5. Shirov's choice also loses to a thunderbolt. 37 Rc7!! The point is to deflect Black's rook from the defence of f6. If now 37 . . . Rxf8 38 Qh4+ wins or 37 . . Qxf8 38 Qxf8+ Rxf8 39 Rxb7 with a winning endgame. 37 . . . Rxc7 38 Qf6+ The point. Although Black will temporarily be a rook ahead he is paralysed. 38 . . . Rg7 39 Nxe6 and in this hopeless position Black resigned 39 . . Nxb2 40 Bxg7+ Kh7 41 Qh6 checkmate is one possible conclusion.

Previous page

Previous page