Theatre

The Lady in the Van (Queens)

The way we live now

Sheridan Morley

We have, in the nick of time, a Play of the Year: Alan Bennett's The Lady in the Van (at the Queens) is a wonderfully bit- tersweet comic diary of the 20 or so years in which a lethally dotty and very smelly old bat parked her unroadworthy vehicle, later in fact two of them, in Bennett's Cam- den garden, thereby providing him with a roughly equal amount of good journalistic copy and guilty landlordly irritation.

As we chuck in the century, it may well be that Bennett is now up there with its half-dozen greatest local playwrights; what is already certain is that he has done far and away the best stage chronicles of its second half, from Forty Years On for 40 years on, reaching back in this latest play to the fragmented revue sketches which were at the heart of his Beyond the Fringe. There may in that time have been more intellec- tually daring or interesting writers, but Bennett alone has consistently told us how we live now, in a permanent state of frus- trated liberal rage; he has also achieved the not inconsiderable feat of having himself played in various moods in this one new play by three actors, not only by Kevin McNally and Nicholas Farrell as the two narrators who bear his name on stage, but also by Dame Maggie herself who, when not resembling the late Kenneth Williams in drag, has now started to do a remarkable impression of her author in similar dis- guise. The Lady is the tramp, and she is simply unmissable and unbeatable; you deserve her for Christmas.

But elsewhere it has not been a good year for new writing, and it is some indica- tion of the terror the West End now has of original scripts, unless they come ready- mixed in transfer from some subsidised starting place, that a play as excellently touching as Simon Gray's The Late Middle Classes should have been allowed to die on the road while its natural Shaftesbury Avenue home was given over to a disas- trous Boyband musical.

What is happening here is a real crisis of identity: at a time when an alarming num- ber of West End theatres are still up for sale or going to foreign conglomerate buy- ers, those who manage them are desperate- ly trying to capture the fringe audience, perceived to be the future, while not losing the older, more conservative tourist and home-county play-goers who are still able to make or break a show on Shaftesbury Avenue or St Martin's Lane. In that confu- sion, some good work is being lost and some terrible work is turning up at good addresses: while the debate thus far has centred on the non-commercial British the- atre and the chaos of its subsidy, we need very soon to start thinking about what kind of West End we want for the new century and precisely how it is to be achieved. If we don't, we shall end up with little more than Abba and Andrew Lloyd Webber.

One of the scariest things you can do, if you have any interest in London playgoing at all, is to compare a current West End titles list with one for about 1955, where you will find a vast range of major local and international, classic and modern drama that is now simply unavailable in central London, where the theatre resem- bles nothing so much as a shrunken head, or at any rate a restaurant menu on which all but about three varieties of food have been deleted.

Another way of scaring yourself into the millennium would be to ask yourself for precisely how long corporate, bottom-line owners are going to be happy with theatres which, listed or not, only bother to open for about three in every 24 hours on prime commercial sites. The sooner we get round-the-clock art exhibitions, restau- rants, wine bars, bookshops and even movie matinees into every West End foyer, the less likely will new owners be to let them simply crumble away of their own accord (most are now nearly a century old) so that they can become the carparks which the conglomerates would vastly prefer.

Not that things are altogether better on the fringe: with the Almeida about to close for a year's rebuilding, the Royal Court only just staggering back to life and the current arts minister, Chris Smith, having achieved the unique distinction of failing to save a theatre in his own constituency, the King's Head, not to mention the Orange Tree in Richmond operating a half-time policy, it is not likely that the off-West End is going to be in any millennial state to fill in the gaps. Then again, the Royal Shake- speare Company seems to regard new writ- ing much as it still regards the Barbican, as a kind of necessary evil, while in an other- wise triumphant year Trevor Nunn's only failures at the National have been the new plays, which have gone from the bad of Hanif Kureishi and Stephen Poliakoff to the much, much worse of their new Battle Royal.

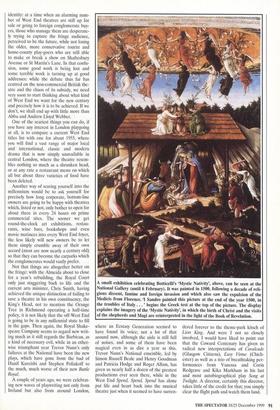

A couple of years ago, we were celebrat- ing new waves of playwriting not only from Ireland but also from around London, A small exhibition celebrating Botticelli's 'Mystic Nativity', above, can be seen at the National Gallery (until 6 February). It was painted in 1500, following a decade of reli- gious dissent, famine and foreign invasion and which also saw the expulsion of the Medicis from Florence. 'I Sandro painted this picture at the end of the year 1500, in the troubles of Italy ... ' begins the Greek text at the top of the picture. The display explains the imagery of the 'Mystic Nativity', in which the birth of Christ and the visits of the shepherds and Magi are reinterpreted in the light of the Book of Revelation.

where an Ecstasy Generation seemed to have found its voice; not a lot of that around now, although the aisle is still full of noises, and some of them have been magical even in as dire a year as this. Trevor Nunn's National ensemble, led by Simon Russell Beale and Henry Goodman and Patricia Hodge and Roger Allam, has given us nearly half a dozen of the greatest productions ever seen there, while in the West End Spend, Spend Spend has alone put life and heart back into the musical theatre just when it seemed to have surren- dered forever to the theme-park kitsch of Lion King. And were I not so closely involved, I would have liked to point out that the Coward Centenary has given us radical new interpretations of Cavalcade (Glasgow Citizens), Easy Virtue (Chich- ester) as well as a trio of breathtaking per- formances from Vanessa and Corin Redgrave and Kika Markham in his last and most autobiographical play Song at Twilight. A director, certainly this director, takes little of the credit for that; you simply clear the flight path and watch them land.

Previous page

Previous page