ZOLA: J'ACCUSE

Kenneth Griffith has made a film about racial prejudice. Television won't touch it.

Gillian Faulkner reports KENNETH Griffith, for more than 40 Years one of our most distinguished actors, film-makers, and exposer of injustices, has Tent most of the last two and a half years In India making a film about the life of Jawarharlal Nehru to coincide with the centenary of Nehru's birth this year. Dur- ing one of his visits home, David Elstein of Thames Television (in Griffith's words 'a most courageous man') suggested that, drawing upon his time and experience in India, Griffith make a film about the Untouchables. Griffith thought that the subject in general and the history of subjugation would be too wide and alterna- tively proposed that the story of this caste should be encapsulated in a film about the life of Dr B. Ranji Ambedkar, a contem- porary of Gandhi and Nehru, prime architect of the Indian constitution and a champion of the depressed castes. A

graduate of both Columbia University and the London School of Economics, Dr Ambedkar practised at the London bar and later, as a member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly, became the leader of 60 million Untouchables.

This putative film received support in India from many sources. The script was settled, studio and crew engaged, but after weeks of prevarication, on 25 January Kenneth Griffith was told he would not get a visa to return to India to make this second film. It is worth noting that one needs government permission to make a film in India. Indian intellectual friends are shocked but powerless.

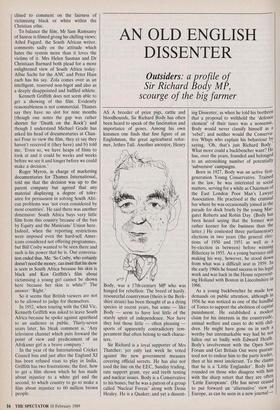

In the last weeks of 1988, Kenneth Griffith made a film about the patent unreasonableness of targeting Zola Budd, a little farm girl from outside a small country town whose talent is to run fast, as Really, I'd prefer to call it a teddy bears' working breakfast.' the embodiment of all the injustices ende- mic in the governing system in South Africa.

The film is thoughtful and well made; it includes footage of Chief Buthelezi, leader of the Zulus and no lover of the existing system, scorning the use of Zola as a spurious symbol. A charming black named Erroll Tobias, the star of the Springbok rugby team, is shown scoring a try while playing for his country and later, in his attractive house, pitying Zola for what had been done to her in the name of justice and making his own kind of gentle appeal for bridge-building. The end of a long road race sees first and second places going to blacks and after them white people who put their arms round those who had beaten them in congratulation just as athletes do in this country; they were all being ap- plauded by a large group of black and white spectators.

Mrs Winnie Mandela declined to be interviewed, though Griffith visited one of her houses in Soweto and her United football team was much in evidence. There is, however, a three-second shot of her shouting, 'We will win through the neck- lace.' Archbishop Desmond Tutu also de- clined to comment on the fairness of victimising black or white within the Christian ethic.

To balance the film, Mr Sam Ramsamy of Sanroc is filmed giving his chilling views; Athol Fugard, the South African writer, comments sadly on the attitude which hates the system more than it loves the victims of it. Mrs Helen Susman and Dr Christiaan Barnard both plead for a more enlightened view of South Africa today. Albie Sachs for the ANC and Peter Hain each has his say. Zola comes over as an intelligent, reserved non-bigot and also as a deeply disappointed and baffled athlete.

Kenneth Griffith does not seem able to get a showing of this film. Evidently reasonableness is not commercial. Thames say they have no slot for nine months (though one notes the gap was rather shorter for 'Death on the Rock') and though I understand Michael Grade has asked his head of documentaries at Chan- nel Four to view the film, they a) say they haven't received it (they have) and b) told me, 'Even so, we have heaps of films to look at and it could be weeks and weeks before we see it and longer before we could make a decision.'

Roger Myron, in charge of marketing documentaries for Thames International, told me that the decision was up to the parent company but agreed that any material displaying a degree of toler- ance for persuasion in solving South Afri- can problems was 'not even considered by most countries'. He said there was another dimension: South Africa buys very little film from this country because of the ban by Equity and the Musicians' Union here. Indeed, when the reporting restrictions were imposed even the hard-sell Amer- icans considered not offering programmes, but Bill Cosby wanted to be seen there and such is his power that he is. Our conversa- tion ended thus. Me: 'So Cosby, who certainly doesn't need the money, can insist that his show is seen in South Africa because his skin is black and Ken Griffith's film about victimising a young girl cannot be shown here because her skin is white?' The answer: 'Right.'

So it seems that British viewers are not to be allowed to judge for themselves.

In 1952, when touring with the Old Vic, Kenneth Griffith was asked to leave South Africa because he spoke against apartheid to an audience in public. Thirty-seven years later, his bleak comment is, 'Any television channel which puts forward the point of view and predicament of an Afrikaner girl is a brave company.'

In the year of the International Cricket Council ban and just after the England XI has been refused visas to play in India, Griffith has two frustrations; the first, how to get a film shown which he has made about injustice to a white girl and the second, to which country to go to make a film about injustice to 60 million brown people.

Previous page

Previous page