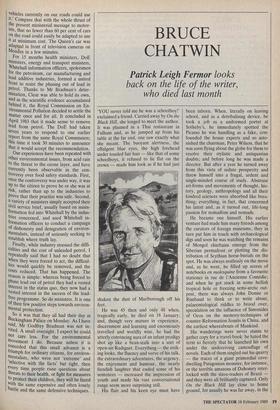

BRUCE CHATWIN

Patrick Leigh Fermor looks

back on the life of the writer, who died last month

`YOU never told me he was a schoolboy!' exclaimed a friend. Carried away by On the Black Hill, she longed to meet the author. It was planned in a Thai restaurant in Fulham and, as he jumped up from his table at the far end, one saw exactly what she meant. The buoyant alertness, the effulgent blue eyes, the high forehead under tousled fair hair — like that of some schoolboys, it refused to lie flat on the crown — made him look as if he had just

shaken the dust of Marlborough off his feet.

He was 45 then and only 48 when, tragically early, he died on 18 January; and, though very mature in experience, discernment and learning and enormously travelled and worldly wise, he had the utterly convincing aura of an infant prodigy shot up like a bean-stalk into a sort of open-air Radiguet. Everything — the strik- ing looks, the fluency and verve of his talk, the extraordinary adventures, the urgency, the enjoyment and humour, the nearly fiendish laughter that ended some of his sentences — increased the impression of youth and made his vast conversational range seem more surprising still.

His flair and his keen eye must have been inborn. When, literally on leaving school, and as a detribalising device, he took a job as a uniformed porter at Sotheby's, he immediately spotted the Picasso he was handling as a fake, con- founded the house experts and so asto- nished the chairman, Peter Wilson, that he was soon flying about the globe for them to resolve their stylistic and antiquarian doubts; and before long he was made a director. But after a year he turned away from this vista of sedate prosperity and threw himself into a frugal, ardent and single-minded course of study. Abstruse art-forms and movements of thought, his- tory, geology, anthropology and all their kindred sciences were absorbed like brea- thing; everything, in fact, that concerned his latest and, as it turned out, life-long passion for nomadism and nomads.

He became one himself. His earlier venture had made him many friends among the curators of foreign museums; they in turn put him in touch with archaeological digs and soon he was watching the remains of Mongol chieftains emerge from the Siberian permafrost or plotting the dis- tribution of Scythian horse-burials on the spot. He was always restlessly on the move and, as he went, he filled up scores of notebooks en molesquine from a favourite stationer in rue de l'Ancienne Comedie; and when he got stuck in some hellish tropical hole or freezing semi-arctic out- post, there was always John Donne or Rimbaud to think or to write about, palaeontological riddles to brood over, speculation on the influence of Simonides of Oeos on the memory-techniques of counter-Reformation Jesuits in China, and the earliest whereabouts of Mankind.

His wanderings were never stunts to gather copy for a travel-book: he hated the term so fiercely that he launched his own under the undeceiving camouflage of novels. Each of them singled out his quarry — the traces of a giant primordial cave- dwelling Patagonian monster, for instance, or the terrible amazons of Dahomey inter- locked with the slave-traders of Brazil and they were all brilliantly captured. Only On the Black Hill lay close to home ground, for usually he was far away, in the Levant, in sinister back-lanes in Bohemia, in Mauretanian deserts, on Athos, in equatorial forests, at Timbuktu, on the Western Himalayan Chain, in Persia, Afghanistan, the Americas or the Anti- podes — indeed, it was there, thanks to days of stranded isolation and downpours on the tracks of migrating Aborigines, that some of the contents of his moleskin notebooks were saved for us in the pages of The Songlines. They were the iceberg-tip, as it were, of two decades of notes, ideas and meditations for the Nomad book. Had he been spared, he possessed all the equipment and the diligence and the ambi- tion to carry it triumphantly through. But the time was too short for him and for us.

His early acquired knack of going straight to the fountain-head led to long and intricate confabulations with Professor Lorenz on twinship and animal behaviour. There were many such encounters. His admiration of the poems of Osip Mande- Istam and the books of his heroic widow, Nadezhda, inspired a special pilgrimage to Russia which I think he never wrote about. Necessarily unannounced, but with due caution and much misgiving, he sought out her flat in Moscow, taking a pot of marma- lade and some half-bottles of champagne with him, and they became friends at once.

He loved company. His knowledge, en- thusiasm and astonishing memory, his comic sense and his gift for mimicry made him a brilliant and staunchless narrator, and when he was alone with a single interlocutor he was perhaps more reward- ing still, as I learnt a couple of winters ago when he came to stay. At grips with The Songlines, he settled for weeks on this steep Morea coast to wrestle with them. His quarters were a flurry of destruction and creation all through the morning and in the afternoon; if he wasn't surfing about the bay in a black scuba suit, we went for enormous walks — sometimes with his wife Elizabeth (who looked after him with such devotion all through the last harrowing months) — but more often alone. Notions and discussions abounded all the way and there was plenty of laughter in the ilex woods. He surged across the headlands and the canyons as though he were in seven-league-boots, only stopping to iden- tify a momentarily puzzling flower or some rare hawk flickering high overhead; halting rather longer to peer at the dark post- Byzantine frescoes, and sometimes the lettering of embedded pagan fragments in the little churches that scatter the Taygatus foothills. Byzantine art calls for a certain historical insight and an interest in religion; but then, Bruce was interested in every- thing; so his more serious turn towards the Greek Orthodox Church a few months ago came as a surprise.

He fought against illness with stoicism and courage. Everyone who knows his work will feel the loss of those books which will never see the light now, and so will all his friends; but, even more, they will miss the energy, the high spirits, the originality and the laughter of their amazingly gifted and suddenly absent companion.

'Could Skippy but speak, m'lud, he would confirm the unswerving probity of my client.'

Previous page

Previous page